This blog was based on the introduction by Psyche Kennett to the new British Council book ‘Creating an Inclusive School Environment’. The blog was written by Deborah Bullock, Freelance ELT consultant, writer and editor, and highlights some key activities taking place around the world to address inclusion when working with displaced populations.

Why a focus on displaced populations in a book on inclusion?

When we talk about inclusion, we automatically think of special educational needs and disability (SEND), but all over the world as a result of conflict or natural disasters, displaced populations are facing exclusion from education. Forcible displacement and the resulting refugee crisis is now a global phenomenon and according to UNHCR (2018), there are no fewer than a staggering 68 million people around the world now displaced due to conflict or persecution.

What are some of the factors that lead to exclusion from education?

Millions of refugees are children and many of these have been out of school for years due to conflict. But there are other factors that also exclude such children from a ‘normal’ education in their ‘new’ host communities – language, ethnic discrimination, religion, school systems and a lack of resources. Add to these trauma, loss, displacement, and fear and it is not difficult to imagine how vulnerable and excluded such children can become.

|

Creating an Inclusive School environment (British Council, 2019) consists of 16 papers authored by a wide range of practitioners and which focus on developing the capacity of school leaders and teachers to create inclusive school environments. They reflect current evidence-based inclusive practice, and research, from around the world by people with first-hand, in-depth experience of the programmes about which they write, and the context in which they are operating. The papers are grouped into four areas – displaced populations; gender and inclusion in the classroom; special educational needs and disability; minority ethnic groups in the classroom – although as the editor of the publication, Susan Douglas, is keen to point out in her introduction: ‘… there are significant intersectionality issues between and among these groups …’ (p10). |

|

What is being done to support children, youth, new teachers and experienced teachers who are displaced or must deal with displacement because of conflict?

In Creating an inclusive school environment, we find four case studies which illustrate how educators and learners are dealing with displacement as a result of conflict:

In Nigeria, where girls and women teachers face vulnerability to violence in its most extreme form, formal and informal interventions are being implemented that support inclusive teaching and learning in ‘safe spaces’. One such intervention is the ‘safe space girls’ clubs’ – community-based informal learning designed to cater for girls who have either dropped out of formal schooling or have no previous experience of it. Here girls learn life skills, build social networks, and access social and psychological services; and female teachers find opportunities to play a meaningful role as providers of care and counselling. The girls’ increased skills have in turn increased community confidence in the value of education for women and girls although there is much still to do in addressing the root causes of gender bias.

In Iraq, the English for Resilience language programme is helping to integrate minority ethnic groups forcibly displaced by ISIS by training new teachers and providing displaced and local youth with much-sought-after English language skills. The programme helps teachers and students to access education and employment and builds social cohesion by learning together in mixed groups. It addresses the effects of trauma on learning, creates safe educational spaces, and develops capacity for dealing with diversity, displacement and inclusion.

In Iraq, the English for Resilience language programme is helping to integrate minority ethnic groups forcibly displaced by ISIS by training new teachers and providing displaced and local youth with much-sought-after English language skills. The programme helps teachers and students to access education and employment and builds social cohesion by learning together in mixed groups. It addresses the effects of trauma on learning, creates safe educational spaces, and develops capacity for dealing with diversity, displacement and inclusion.

Standing in front of a class for the first time is daunting for anyone, but one coach from Fallujah was particularly unsure about giving his first lesson. With the help of his colleagues, however, he was able to prepare and deliver the activity well. Later we discovered that he had witnessed one of his family members being killed by Daesh[1] before he and his parents managed to flee to Erbil. The fact that this young man successfully finished the course with the support of his peers was incredibly empowering for him in the light of what he had experienced. In most cases we don’t know what the coaches and beneficiaries have been through, and in fact it is not necessary to know. Whatever their story, we are creating a safe and supportive environment where new positive experiences take place. (p 27)

In Greece, the Living Together training incorporates lessons learned from informal education programmes to strengthen inclusive practices for refugees and migrants in the formal Greek education system. The programme builds a positive loop around inclusive alliances for inclusion. It works with integrated groups of state school and non-governmental organisation (NGO) refugee camp teachers, school leaders and environment, health and culture education professionals. It advocates inclusive pedagogy, life skills and a rights-based approach to deal with multilingual, multigrade, psychosocial challenges

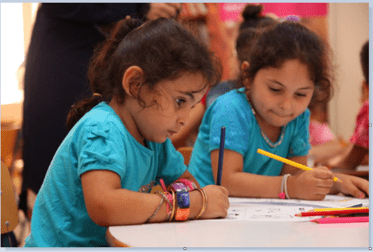

In Lebanon, which hosts a higher density of refugees per capita than any other country in the world, a plurilingual approach to inclusion for very young learners is being introduced in the Lebanese preschool system. The practical training pack is designed to link teachers, young children and their parents in a positive class–work, home–work cycle and ‘awaken’ children, parents and teachers to linguistic and cultural diversity and inclusion. The very simple pre-primary multilingual tasks also support parents who do not understand the Lebanese school system, cannot necessarily communicate with their child’s teacher, and may be semi-literate themselves. The impact of the approaches in the pack became apparent by a marked shift in attitude among teachers, children and their parents:

In Lebanon, which hosts a higher density of refugees per capita than any other country in the world, a plurilingual approach to inclusion for very young learners is being introduced in the Lebanese preschool system. The practical training pack is designed to link teachers, young children and their parents in a positive class–work, home–work cycle and ‘awaken’ children, parents and teachers to linguistic and cultural diversity and inclusion. The very simple pre-primary multilingual tasks also support parents who do not understand the Lebanese school system, cannot necessarily communicate with their child’s teacher, and may be semi-literate themselves. The impact of the approaches in the pack became apparent by a marked shift in attitude among teachers, children and their parents:

Awakening to languages made me change my opinion about Syrians not being good. Now I think that – no, we can be equal. Somehow, I make mistakes and they make mistakes. (Lebanese teacher)

Awakening to languages made me change my opinion about Syrians not being good. Now I think that – no, we can be equal. Somehow, I make mistakes and they make mistakes. (Lebanese teacher)

We thought before that the children were stupid, but we learned that there is no stupid student. (Syrian mother)

Before, I asked questions in Hourani, but they didn’t understand me. Now when

I speak to them, they understand me. I speak with them a little in Lebanese and a little in English, and they also learn a bit of Hourani. We adapt one to the other to understand each other. (Syrian boy)

Further information on each programme can be found in the British Council publication Creating an inclusive school environment, edited by Susan Douglas, 2019.

[1] Daesh is the term that the UK government uses to refer to the extremist group otherwise known as IS, ISIS or ISIL.

Nice content you posted thanks for sharing this details with us.