This blog was written by Daniel Omaya, Head of School Network for PEAS (Promoting Equality in African Schools) in Uganda. Here he shares the challenges he has been facing while implementing an innovative remote education programme. This article has also been published on the PEAS website.

This year saw a drastic turnaround to events, caused by the world-wide outbreak of COVID-19. With multiple sectors affected, education was no exception. In Uganda, a nationally-broadcast Presidential address on COVID-19 on March 18th announced that all education institutions expected to be closed within two days across the country for a period of 30 days. This was done in the best interest of learners’ safety, given over 15 million children and young people were studying in education institutions at the time. While a lot of the world is now starting to reopen schools, at the time of writing, we do not yet know when schools will reopen in Uganda.

Challenges of school closures

School closure was mostly unanticipated, especially since there were no cases in the country at the time. Many parents raised concern over the abrupt school closures: What would become of the school fees they had paid – especially those that had paid 100%? How would they be able to provide food to their children, for a period they planned for them to be at school? There were rays of hope, as schools were only going to be closed for one month. However, as the number of infections began to rise, the light of hope burned out and, two weeks later, a nation-wide lockdown was introduced, alongside curfews. More uncertainty loomed throughout the country – how was learning going to continue? Would schools reopen to complete the half-term? How safe will schools be? How ready was Uganda for online/virtual learning?

School closure was mostly unanticipated, especially since there were no cases in the country at the time. Many parents raised concern over the abrupt school closures: What would become of the school fees they had paid – especially those that had paid 100%? How would they be able to provide food to their children, for a period they planned for them to be at school? There were rays of hope, as schools were only going to be closed for one month. However, as the number of infections began to rise, the light of hope burned out and, two weeks later, a nation-wide lockdown was introduced, alongside curfews. More uncertainty loomed throughout the country – how was learning going to continue? Would schools reopen to complete the half-term? How safe will schools be? How ready was Uganda for online/virtual learning?

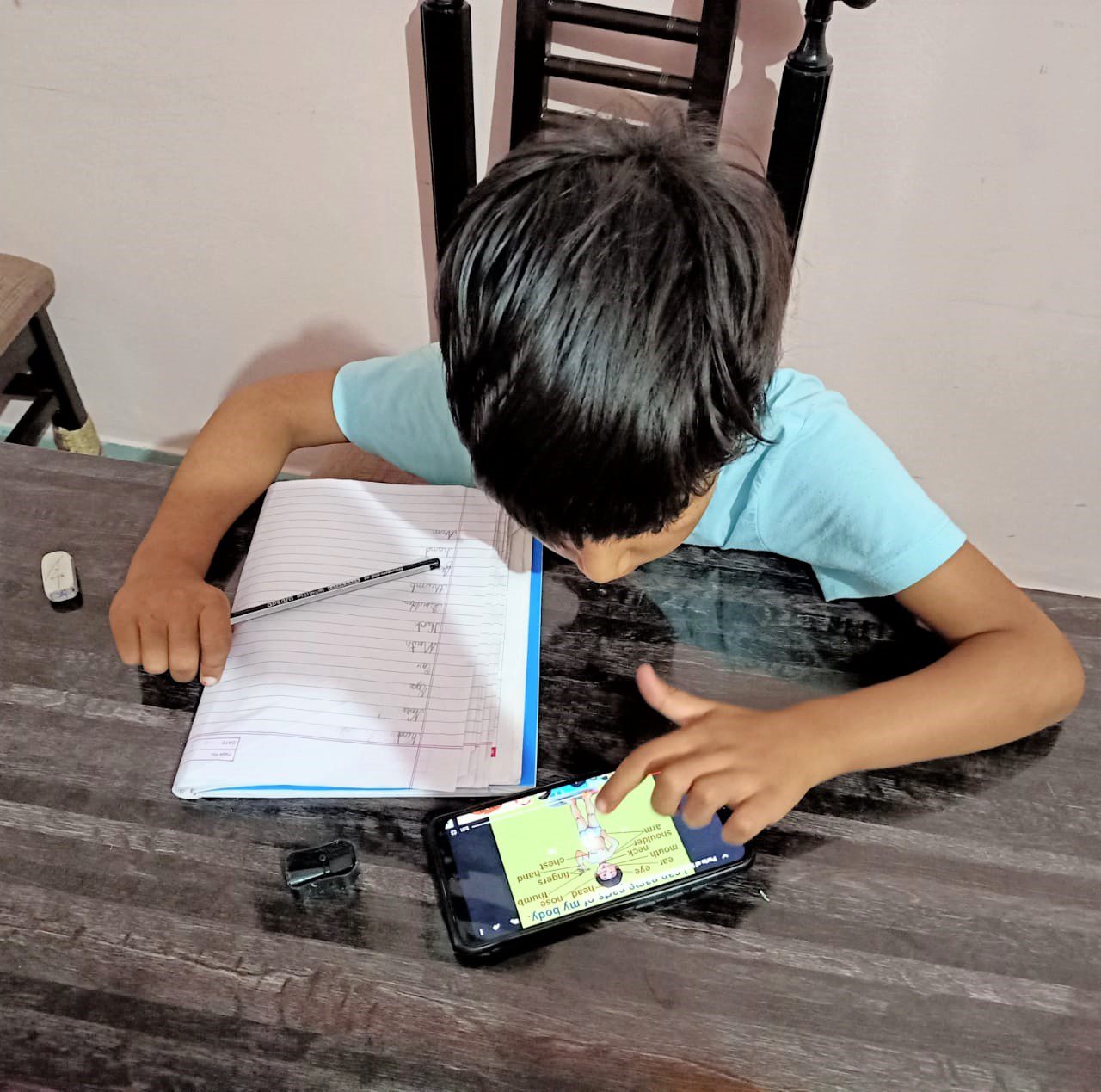

As Head of School Network, my job at PEAS-Uganda is to oversee the delivery of our support programme to our network of 28 schools. Guided by access and equity, we are driven by the urge to serve the hard-to-reach children. Our schools serve rural, low-income communities and very few of our students have access to a computer, the internet, a tablet or a smart phone. As soon as school closures were announced I knew immediately that we would need to find ways of reaching out to the students that did not rely on sophisticated hardware or an internet connection.

We knew that our priorities would be to keep our students, especially our girls, as safe as possible, try and keep students engaged with their education and maximise the likelihood that students will return once schools reopen. After a lightning quick review of the available evidence, we narrowed down on four main no- and low-tech approaches to help us achieve these things: radio, text messaging, telephone communication and the provision of self-study packs (if and when it became possible to distribute these safely). We decided to focus on content covering health, safeguarding and education topics.

We knew that our priorities would be to keep our students, especially our girls, as safe as possible, try and keep students engaged with their education and maximise the likelihood that students will return once schools reopen. After a lightning quick review of the available evidence, we narrowed down on four main no- and low-tech approaches to help us achieve these things: radio, text messaging, telephone communication and the provision of self-study packs (if and when it became possible to distribute these safely). We decided to focus on content covering health, safeguarding and education topics.

Challenges at the school level

It is now early June and we’ve been implementing our remote education programme for over two months. Implementing this unique intervention has been a learning process for us, especially given that we do not have experience of managing a crisis of this nature. We have had to juggle managing familiar challenges such as power cuts and poor internet connection with new challenges, three of which I’ve highlighted below:

Avoiding undermining school leaders while communicating directly with families and communities.

During this period, PEAS has set up new communication channels out of necessity that involve direct communication with families. School leader autonomy is a core part of our model so we have wanted to avoid leaders feeling undermined. We have done this by consulting leaders during the design of our remote education programme. We also have a school leaders’ WhatsApp group where ideas are constantly shared and discussed. While our direct contact with families is largely through the SMS system, we have protected school autonomy by supporting class teachers to contact families through follow-up phone calls. Interestingly, families have managed to contact our leaders in appreciation; feedback from leaders indicates that “PEAS…has created a strong relationship between the schools and community, as well as staff”, suggesting that we’ve managed the situation well so far.

During this period, PEAS has set up new communication channels out of necessity that involve direct communication with families. School leader autonomy is a core part of our model so we have wanted to avoid leaders feeling undermined. We have done this by consulting leaders during the design of our remote education programme. We also have a school leaders’ WhatsApp group where ideas are constantly shared and discussed. While our direct contact with families is largely through the SMS system, we have protected school autonomy by supporting class teachers to contact families through follow-up phone calls. Interestingly, families have managed to contact our leaders in appreciation; feedback from leaders indicates that “PEAS…has created a strong relationship between the schools and community, as well as staff”, suggesting that we’ve managed the situation well so far.

Communicating during a crisis.

All of a sudden, email correspondence became almost obsolete for school leaders, given some of them got locked down in remote locations without an internet connection. The connection and relationships we would build in leaders and teachers through face-to-face interactions has disappeared during lockdown. Nonetheless, opting for telephone conference calls instead has bound us all together, alongside group and individual text messages to the teams. These require no internet access and I am glad that together with the team, we have managed to circumvent the communication challenges.

Adapting at speed, maintaining morale and motivation during uncertainty.

One of our values is ‘Be entrepreneurial’ but this has taken on a whole new meaning during a crisis. Working and planning during a time of such uncertainty (How can our staff move around when many travel on the back of a motorcycle? When will schools be able to reopen?), has meant many false starts – we spent almost a week designing learning packs for our students before the lockdown was announced and then quickly pivoted to radio. We’ve maintained high levels of motivation by agreeing that there will always be a ‘new normal’ to adjust to, holding regular virtual meetings and shared success stories gathered from parents and leaders.

Personal challenges

Like many other people in Uganda, I have been trying to deliver this programme and support my team in difficult personal circumstances. I experienced the national lockdown while in a remote village in Northern Uganda. In my village, it doesn’t matter whether you have the gadgets, there will always be no internet access, and high intermittent phone network connectivity. With the simplest solar system, I could not charge my laptop. I managed to secure a room at a local trading centre, to enable me to connect both on phone and internet to reach out to my team. Where skype is too heavy for the connectivity, I have manoeuvred through WhatsApp calls. Despite these challenges I have felt reassured and motivated to know that what we’re delivering is helping our communities. Community feedback after radio lessons overwhelmingly shows enthusiasm to support learners during this time. One of our parent’s reflections was that “PEAS has come closer to us, beyond the school environment. The phone calls show personal concern for my child and I am grateful”. Such feedback drives us to support further. We are not going to stop, however long closure lasts.

Partnership and collaboration are part of our DNA as an organisation, so all of our materials are open source and we have a section here on the PEAS website where you can access them.

Daniel indeed the interventions we have put in place have created a great impact in the community. Telephone call intervention, radio lessons and distribution of learning packs have made us to keep in touch with parents and students, know the challenges they are facing and has given us opportunity to guide and counsel them. Thanks to PEAS- UK and PEAS- Uganda for being a genuine organization.

ONYAIT DEO

Head teacher

Toroma PEAS high school – Uganda

Dear Daniel,thanks for this great piece of work.Daniel, i must say,all the interventions you have taken lead on have been a success amidst the hardships we met ,nevertheless,the learners ,parents, are greatly appreciative of the ongoing toils and sacrifices you are making in delivering learning to our disadvantaged cohort of students in the country.Indeed Peas as an organisation has established a strong ground in the communities in terms of education this is evidenced by phone calls we get from non peas parents giving us assurance of how they are prepared to bring their learners to our schools as soon as schools’ open.

Bravo to Peas.

Daniel that was very interesting as we are on a similar situation in Sudan – but this time with training teachers

We are also using what’s app, hard copy materials (when we can deliver them) and radio. Like you – no internet or electricity access.

Thank you Anne. It is altogether an innovative approach to reach out to beneficiaries despite the challenging contexts. I am particularly interested in understanding your approach to delivering teacher training during school closures. Our outstanding impediment around this is that the IT levels of teachers vary and at the same time, teachers are not in one place at the moment. Thank you.

Omaya, thanks for sharing yo experience. You very well know that when others learn that there are other people else where facing the same challenges they are going through, it gives them courage b’se they get to know that they are not alone. Or possibly they get relief after knowing others are worse off.

My OB. All I want to say is “It’s not the same without your post.”