This blog post was written by Arathi Sriprakash, Sociologist of Education at the University of Cambridge. It is a reflection on discussions that took place at a seminar on “Questions of Race in Education and International Development” which she convened with Leon Tikly (University of Bristol) and Sharon Walker (University of Cambridge). The event was funded by the British Association of International and Comparative Education and the British Academy.

Issues of racism within the field of education and international development are rarely addressed directly, despite profoundly shaping our research, policy and practice. This ‘area of silence’ means that we haven’t adequately developed the concepts or approaches to understand the operations of racism in our work. There is an urgent imperative to do so if we are to take social justice concerns seriously, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) commitment to ‘leave no one behind’.

Indeed, an analysis of racism should be integral to understanding educational inequalities. Global Islamophobia, indigenous dispossession, forced displacement and migration, racial segregation, casteism, communal violence, and ethnonationalism so clearly affect educational processes, distributions, and exclusions.

Starting a conversation

In February 2018, we held a seminar at the University of Cambridge, attended by scholars, policy actors and activists, which aimed to get us talking directly about the challenges of racism in our field.

The event posed four key questions for debate:

- To what extent does our research, policy, and practice attend to the historically specific ways that racism shapes the educational contexts in which we work?

- In what ways do the theories, measures, tools, and approaches we use to understand educational inequality enable us to see or not see racism?

- How can we address the racialised politics of knowledge production in our field? That is, who does what work, where, and under what conditions, to produce knowledge about development?

- What would an anti-racist agenda look like for research, policy and practice in education and international development?

In order to unpack some of these questions, Sharon Walker presented her findings from a systematic literature review of key journals in our field. Her analysis showed that issues of racism are overwhelmingly left unaddressed in research on education and international development.

Considering the policy implications of this, Leon Tikly argued that a failure to address racism would only produce unsustainable development. However, he suggested that the SDGs offer an opportunity: they compel us to consider inequalities across the global, north and south – between and within nations. Tackling these inequalities arguably requires us to develop a strong race justice agenda.

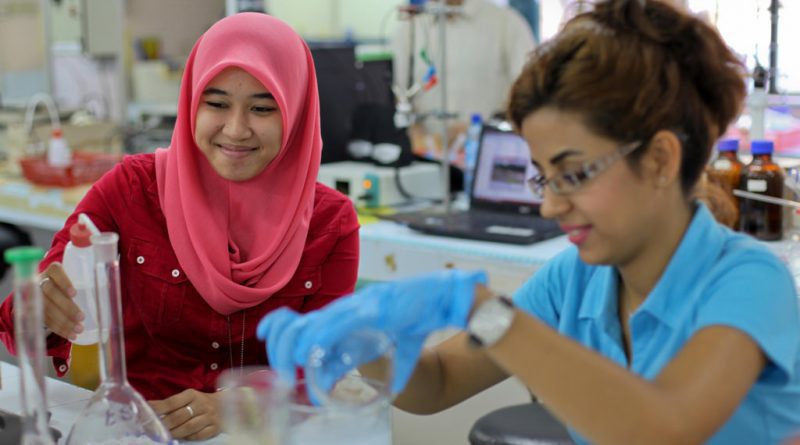

Fazal Rizvi’s presentation on the contested, racialised, foundations of humanism within UNESCO’s global development agenda since its inception, encouraged us to historically situate the notion of ‘sustainability’ – a term that remains ill-defined in the field. Kalpana Wilson’s paper then challenged us to think about the articulation of racism within educational programmes that position girls as resources for development, specifically as entrepreneurs in the service of global capitalism.

Policy dilemmas

A lively policy forum with Pauline Rose (REAL Centre, Cambridge), Amanda Lenhardt (Save the Children) and Jordan Naidoo (Education 2030, UNESCO) raised a challenging question: what should be the policy priorities for tackling issues of racism?

Participants debated whether issues of racism could be measured and monitored, and whether it was possible, or even desirable, to formulate ‘global’ indicators for race justice, given the different and contextually specific formations of racism. Racism impacts so many domains in education, such as: access and outcomes of schooling; language in education policy; curriculum and pedagogy; global governance; and monitoring and evaluation.

Our understanding of racism, it was argued, cannot rely on fixed categories of ‘race’, given that ‘race’ is socially constructed. Instead, we need to draw analytic and political attention to the processes through which racial inequalities are formed. Yet the dominant model of producing data for evidence-based policy leads to ‘race’ being the object of analysis (often via the formulation of ‘ethnicity’), rather than the contingent formations of racism. This risks a reductive approach to race justice that may reinscribe false biological distinctions between groups.

Can racism only be addressed if it gets measured?

Is it only possible for our field to recognise and address the dynamics and effects of racism through the paradigm of measurement, indicators, and monitoring? This remained an unresolved issue. One delegate reflected that it was not in the interest of the global development architecture to develop an anti-racist agenda, suggesting this agenda needed to come from below, through social movements. Discussions also touched on the possible lessons that could be learnt from the advocacy of disability and gender issues within the field.

Poignantly, the seminar ended with an emotive reflection by a number of people of colour in attendance about the burden of carrying these tasks, despite issues of racism needing to be owned collectively. This was seen as particularly problematic in a field which is dominated by what one participant called ‘Eurocentric prisms’.

Indeed, addressing racism is challenging and unsettling. It is the responsibility of us all. So please share your thoughts and actions. How should an agenda to tackle racism be developed in our field?

Lovely summary, Arathi, with hugely important questions. Thank you for starting this conversation, which I hear is to continue in Bristol. Looking very forward to that!

Adopt a critical race theory approach – “CRT is a body of scholarship steeped in radical activism that seeks to explore and challenge the prevalence of racial inequality in society. It is based on the understanding that race and racism are the product of social thought and power relations; CRT theorists endeavour to expose the way in which racial inequality is maintained through the operation of structures and assumptions that appear normal and unremarkable”.

CRT is based on understanding and opposing systems that subjugate peoples of colour and recognises how other systems of subordination interact and reinforce each other in complex and many ways at the same time, e.g. gender and race, or “intersectionality” as first coined by Kimberle Crenshaw (1989) In relation to the UK, the work of Dr Nicola Rollock and Professor David Gillborn are extremely relevant in the context of race, racism and education.