By Dr Sharon Tao, Gender and Inclusion Adviser for Cambridge Education and UKFIET Executive Committee member. This blog was originally written for UNICEF and posted on 16 April 2018. Reposted with permission.

UNICEF has commissioned 10 papers by leading researchers and practitioners to stimulate debate around educational challenges in Eastern and Southern Africa: a region where most children attend school, but many are not learning the basics. While the articles have academic roots, they are not research papers, nor do they represent UNICEF policy. Rather, they are engaging pieces to inspire fresh thinking to improve learning in Eastern and Southern Africa and globally.

It’s encouraging to look back over the last ten years and see that a lot of work has been done to improve girls’ education — a lot more is known about “what works” in certain circumstances. But the problem of poor learning outcomes for girls persists. Partly because girls face multiple levels of constraints, some of which, particularly those based in cultural and religious norms, need a great deal of time and care to shift. Another aspect is that efforts to tackle constraints are often too disparate, narrowly focused, short-term or too small to have major impact.

Therefore I am putting forward a new approach to girls’ education – one to galvanise and coordinate efforts so that more comprehensive and sustainable change can be achieved.

In Eastern and Southern Africa, tremendous progress has been made towards achieving gender parity in the first few years of primary school. However, in the following years, girls’ presence and participation starts to drop, leading to very poor completion and transition rates. To understand why girls’ education suffers, let’s consider the constraints that affect girls’ education.

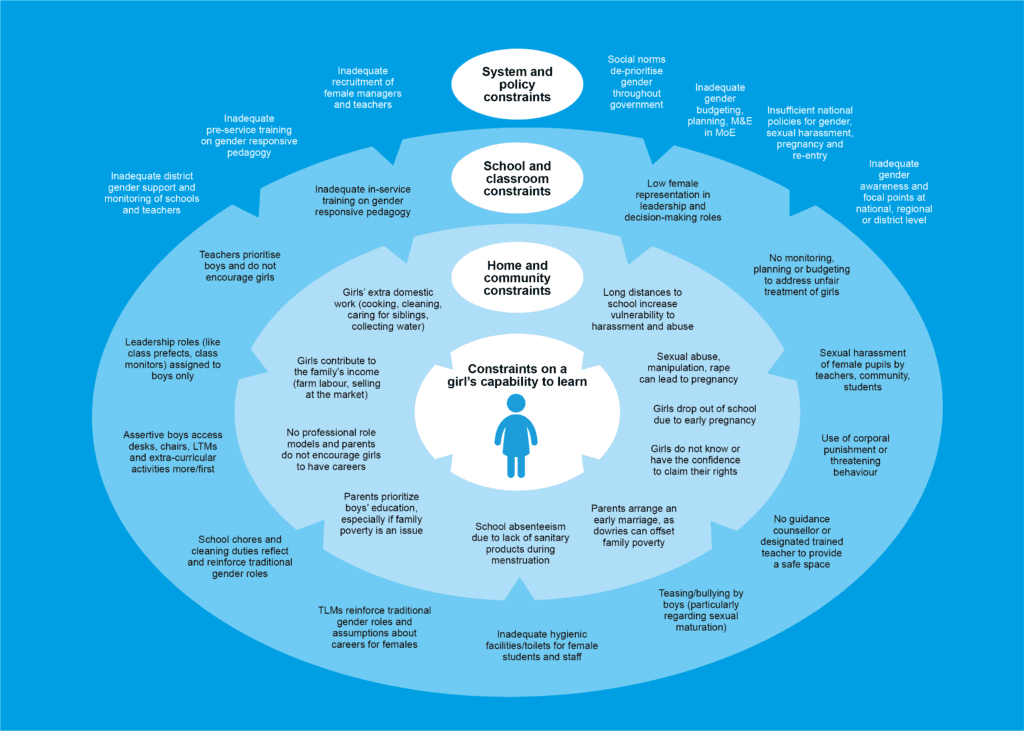

The figure below (click for larger image) outlines constraints within the different levels of the education system:

- Home and community

- School and classroom; and

- System and policy

Such analysis helps illustrate how inequalities affecting girls’ education are complex, interconnected and compounded from the macro- to micro-level.

Many international partners, donors and governments have implemented interventions to address constraints; however, they generally focus on only one or two constraints at just one of the levels of the education system. This can be a problem, as projects focusing on school constraints can easily be undermined by constraints that still exist within the home (or vice versa). No single intervention on its own can improve girls’ education in a sustainable way. A lack of comprehensive approach is why girls’ inadequate achievements persist.

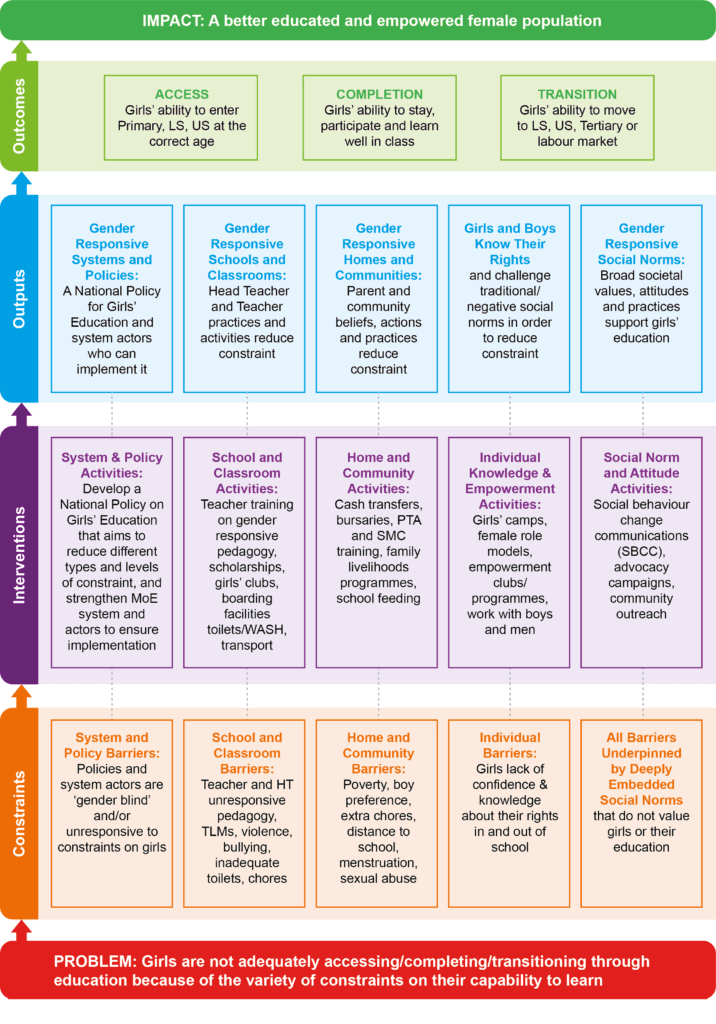

Thus, I am putting forward an approach that looks at the overall problem and coordinates interventions towards a comprehensive strategy. It entails ministries of education to:

- Develop a comprehensive Theory of Change (ToC) to underpin their gender responsive sector plan or national gender in education policy

- Use the ToC to guide implementation: it provides a common strategy and coordination mechanism for both system actors and like-minded organizations working on girls’ education interventions

An example of such a transformative approach can be seen in the figure below. It starts with different constraint types and levels and provides corresponding interventions. Discussions with key stakeholders, particularly girls, are imperative to validate constraints and to help prioritise constraints and interventions in specific districts or regions.

This transformative approach can be used as a clear roadmap to keep all system actors, organizations and projects focused and aligned. The hypothesis is that if interventions are implemented simultaneously and in the same context, more gender responsive systems, schools, homes and communities will begin to develop. When that happens, girls’ educational access, and completion will improve significantly.

Such an approach is not easy: it takes leadership and political will from ministries of education to develop, own and drive this transformative approach. But if all partners support ministry leadership and training and actively promote coordinated effort, it is possible to achieve meaningful change for girls’ education. Because it is only through working together – from the macro- to micro-level and through government and non-governmental partners – that we can truly transform our investments in the education and lives of girls. Now, and for years to come.

Dive deeper into this topic:

- Read the complete Think Piece on girls’ education (8 pages, 10 min read)

- Watch a summary presentation by the author (mp.4, 20 mins)

Dr Sharon Tao is a Senior Education and Gender Adviser from Cambridge Education with extensive experience of implementing large-scale, DFID-funded education programmes in Ghana, Tanzania, Nigeria, Uganda, Sierra Leone and India.

Hey Sharon, Good one – particularly like the single page summary.