By Dr Elizabeth Spier (American Institutes for Research), Hirokazu Yoshikawa (New York University) and Paul Oburu (New York University and Maseno University, Kenya). This blog was originally posted on the UNICEF website on 29 May 2018.

© UNICEF/UNI87197/Noorani

During a physical exercise session, Ms. Moonlight Olives (46), walks with children outside the Kisojo ECD Center in Kyenjojo district in western Uganda. After receiving UNICEF supported training on ECD (Early Childhood Development) (ECD) Caregivers, Ms. Olive helped establish an ECD Centre with help from her community.

Quality pre-primary education is critical to a child’s cognitive, social and emotional development, growth, school readiness and future economic potential. However, only 42 per cent of children in sub-Saharan Africa participate in any organized pre-primary education before the typical enrolment age for grade one. And those that do are not all learning in a child-friendly and rights-based environment where developmental and learning needs are effectively supported.

Investment in pre-primary education must go beyond access to include quality and equity not least because low-quality early childhood education has limited or even negative effects on children’s development. Alternatively, children having supportive and trusting relationships with teachers, typically have better-regulated levels of stress hormones. This fosters positive development and learning.

Why is quality pre-primary education lacking in many countries?

Despite strong evidence and increased support from policy-makers and communities, access and quality issues persist in low-resource contexts. These include:

- Undervaluation of early childhood as a critical period of development.

- Widespread misconceptions about what constitutes quality pre-primary education.

- Focus on access alone, that compromises quality.

- Multiple conflicting priorities across nutrition, health, social protection and child protection.

- Lack of accountability for quality and equity in pre-primary education.

Some promising approaches in action

To be scalable and sustainable, pre-primary education models must address insufficient human resources at a cost governments can afford. Some examples of promising approaches that address these challenges are:

- Equipping local community members, including parents, with skills to provide pre-primary education — BRAC pre-primary schools in Bangladesh and Hippocampus Learning Centres in India.

- Accelerated school readiness training for grade one teachers or community volunteers — Education Quality Improvement Programme in Tanzania’s School Readiness Programme.

- “Hub and spoke” models of pre-primary education where a high quality centre becomes a best practice hub and serves as a resource for surrounding centres (spokes) — the Kidogo model in Kenya.

How can we ensure quality pre-primary education for all?

Establishing quality, sustainable pre-primary education systems requires societal changes in the perception of pre-primary education and educators, and a willingness to abandon quick wins in favour of longer-term gain.

- UNICEF education specialists and other international partners can engage in information-sharing and advocacy with policymakers and other stakeholders who have the power to drive system-level change.

- Innovative approaches can challenge beliefs and practices that perpetuate the low status of pre-primary education and educators, among policymakers, parents and the public.

- To receive the oversight, funding, and other resources required to reach all children, the system requires national quality standards, leadership and data systems; local level training and monitoring systems to ensure program quality; and subnational governance for effective national and local coordination.

- To provide universal, quality pre-primary education in the region, we need substantial and long term investment from governments and donors to: identify best practices; adapt to scale; and develop the necessary support systems to manage and sustain the system.

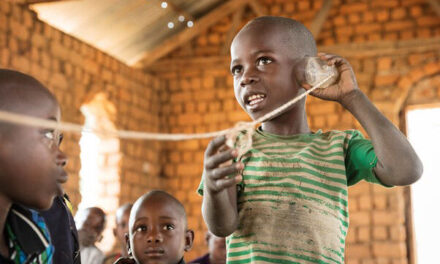

©UNICEF/UNI42760/Nesbitt

Smiling pre-school children at the UNICEF-supported Consol Homes Orphan Care in the village of Namitete, near Lilongwe, Malawi.

There is a strong need for quality, universally-available pre-primary education in Eastern and Southern Africa. Donors and government partners can best help countries improve their children’s equitable access by enabling environments and capacity (rather than investing directly in programming).

A large-scale shift in priorities, combined with investment in the development of strong systems can provide quality pre-primary education for all.

Dive deeper into this topic:

- Read the complete Think Piece on quality pre-primary education (8 pages, 10 min read)

- Watch a summary presentation by the authors (mp.4, 20 mins)

Dr. Elizabeth Spier is a Principal Researcher for American Institutes for Research, and specializes in impact studies and technical assistance in the areas of child development, school readiness, conditions for learning, and parenting support.

Hirokazu Yoshikawa is a University Professor at New York University, co-director of the Global TIES for Children Center, and conducts research on programs and policies in early childhood development in low- and middle-income countries.

Paul Oburu is a Research Associate Professor at New York University and Associate Professor of Psychology at Maseno University, Kenya. He is the project director of Education Quality and Learning for All (EQUAL) Global Research Network based at New York University and New York University-Abu Dhabi.