This blog was written by Peter Sutoris, PhD Candidate and Gates Scholar at the Education Faculty, University of Cambridge. He is the author of Visions of Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016) about development ideology in postcolonial India and the film The Undiscovered Country (Alexander Street Press, 2013) about education and development in the Marshall Islands.

This blog was written by Peter Sutoris, PhD Candidate and Gates Scholar at the Education Faculty, University of Cambridge. He is the author of Visions of Development (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016) about development ideology in postcolonial India and the film The Undiscovered Country (Alexander Street Press, 2013) about education and development in the Marshall Islands.

For the 2017 UKFIET conference, 23 individuals were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their experience.

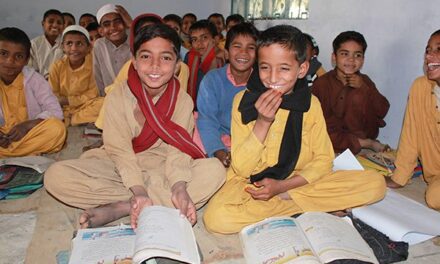

We talk of education for sustainable development, but we forget that sustainability is a radical concept to many in this world. To talk of educating young people for sustainability inevitably means to be political, i.e. to confront the uncomfortable realities of our increasingly neoliberal, corporate world—the very structures that make our societies unsustainable in the first place. Much of the scholarship about education in the era of sustainable development is a far cry from this idea: for decades, the debates have centred around providing access to school for all children without thinking much about what happens inside the school when the students get there.

More recently, the focus has been expanded to the idea of ‘quality’ education. Yet, many of the measures of quality available to us are overly simplistic and reductionist in nature; much of education is still perceived through the optics of inputs and outputs, without understanding the social, cultural and political processes through which learning happens. Many in the field of educational development cling onto the idea that ‘quality’, an inherently complex and context-dependent concept, can be understood through purely quantitative, positivist, universalist approaches to education research. We too often equate education with schooling, eschewing the myriad of other ways in which young people learn. In other words, much of scholarship about education as a means to sustainable development fails to challenge the depoliticisation of education; it indeed reinforces it.

Based on my ethnographic research in communities in India and South Africa, that have suffered from various forms of environmental injustice, I argue that education for sustainable development is inherently political, even though governments and development organisations often strive to depoliticise it. The ability to question social structures—to recognise inequality, to rally around an issue, to imagine agency as extending beyond the self’s immediate microcosm, to challenge authority—is core to any attempt to harness the transformational potential of education in advancing sustainability. Indeed, my research suggests that much of our discourse around education in the ‘Global South’ is lopsided, seeing impoverished and marginalised communities as sites of ‘intervention.’

I argue that we ought to, instead, see at least some of them as sites of ‘inspiration’. Communities that live on the fence lines of factories (as is the case in my South African research site) or have been ousted by a government mega-dam project (Indian site) have much to teach us about how to stand up to forces of unsustainable development. These communities show us that young people need not become apathetic about the ‘greater good’, that instead of depoliticising sustainability and environmental degradation, we can harness the curiosity, energy and idealism of young people.

They teach us that activism is a form of education. It’s high time that the rest of the world wakes up to the simple idea that cultivating activism is the key ingredient we need if we are to make the world sustainable again.