This blog was written by Kashfia Latafat, research scholar at Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development.

Social studies, as a field of education, carries the responsibility of preparing young learners to understand their societies and to participate meaningfully as active citizens. However, in many classrooms, social studies is limited to the memorisation of facts, dates and state-approved narratives that give preference to obedience to rote learning over critical inquiry. This approach, often termed “banking education” by Paulo Freire, reflects a vision of teaching where knowledge is deposited into passive learners rather than constructed collaboratively. Such teaching reproduces dominant ideologies and strangles opportunities for critical thinking.

Paulo Freire’s philosophy of critical pedagogy advocates for an alternative: education as an exercise for freedom. Freire discussed that teaching must not only transmit knowledge but also help learners become critically aware of their world and empower them to raise their voices for transforming unjust structures. His principles remain highly applicable for teaching social studies in today’s globalised and often divided societies. This blog analyses how Freire’s ideas can highlight emancipatory approaches to social studies teaching, focusing on three central features: dialogue, critical consciousness and praxis, whilst signposting practical ways for classroom application.

The banking model of education and social studies

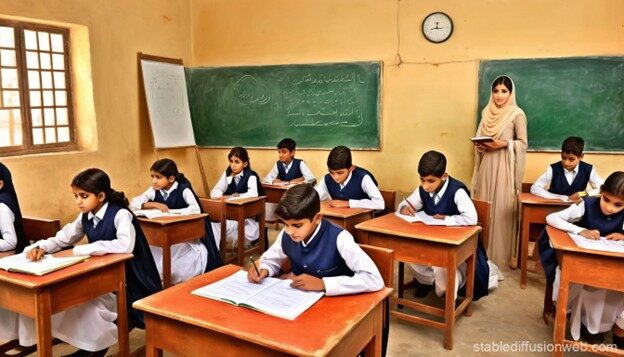

Freire’s critique of the “banking model of education” highlights a critical lens to evaluate the boundaries of traditional social studies teaching. In this model, teachers are considered the sole owners of knowledge, and students are handled as empty vessels to be filled. The teacher narrates, and students memorise, often not allowed to ask questions or apply knowledge to their lives.

In social studies, this approach establishes a form of textbook-driven instruction, where official versions of history, citizenship and social values lead the curriculum. For example, students may be obliged to memorise the founding dates of states, debates of political leaders or suggested versions of national identity, without any consideration of marginalised perspectives or disputed interpretations. Such teaching imitates hegemonic ideologies that benefit the powerful, rather than prepare learners to critically observe their world.

Freire brlieves that this style of teaching dehumanises students by rejecting their capacity for reflection and transformation. Instead, he advocates for a “problem-posing” model of education where learners and teachers connect as co-investigators of reality. For social studies, this means transforming classrooms into spaces where students not only acquire knowledge but also question whose knowledge is being prioritised, whose voices are silenced and what implications this has for democratic participation.

- Dialogue as a foundation of emancipatory teaching

A cornerstone of Freire’s pedagogy is the concept of dialogue. Unlike the unilateral approach of banking education, discussion founds a horizontal association between teachers and students. Discussion is not merely conversation but a collective process, where both sides learn from one another.

In social studies classrooms, discussion develops opportunities for learners to query and recreate dominant narratives. For instance, while learning colonial history, learners could be encouraged to re-evaluate tales of colonisers beyond verbal histories and cultural reminiscences of colonised communities. This procedure confirms students’ lived practices and community knowledge while challenging the notion that official textbooks provide the only truth.

Inclusivity is also nurtured through dialogue. Social studies examine subjects of identity, culture and politics where learner standpoints are diverse. By using dialogue, educators can promote respectful debates and discussions that show learners’ various perspectives and exhibit democratic practices within the classroom.

- Conscientisation and critical thinking in social studies

An additional critical Freirean principle is conscientisation, or critical consciousness. Conscientisation observes social, political and economic ambiguities and acts against oppressive features of reality. For Freire, education without critical consciousness merely reinforces the status quo; with it, education becomes emancipatory.

In social studies, conscientisation can be fostered by linking the curriculum to learners’ lived realities. For example, a lesson on citizenship should encourage students to reflect on who has permission to avail full citizenship rights and who remains marginalised. Likewise, in learning about economic systems, students can evaluate how poverty, labour rights or gender disparity affect their communities.

By boosting critical reflection, teachers can enable students to look beyond surface-level knowledge toward an awareness of structural inequities. This can lead learners to question the social order, rather than passively accepting it. For example, through critically analysing media portrayals of migrants or minorities, thereby recognising how ideology operates in shaping public opinion. Such critical literacy skills are vital for democratic societies, where informed citizens must navigate competing narratives and power-laden discourses.

- Praxis: Linking reflection and action

For Freire, true emancipation starts through praxis, the ongoing process of reflection in and on action. Education should motivate learners to use their knowledge towards transforming unfair realities. Without action, critical consciousness remains incomplete; without reflection, action is unguided activity, which often leads towards misjudgments.

For cultivating praxis, social studies is an appropriate avenue, as it deals directly with social, political and ethical issues. Learners can be trained to translate their classroom learning into projects that can be used to develop their understanding about real-world concerns. For example, after learning about environmental policies, students may be able to design awareness campaigns on local climate issues – thereby becoming change agents.

Freire’s vision of education as a practice of freedom, moves learners from being passive listeners to active contributors in shaping society. Significantly, praxis also changes teachers to facilitators of critical inquiry and social action, rather than transmitters of knowledge.

Teaching strategies

To translate Freire’s ideas into practice, one strategy in social studies is the use of Critical Dialogue Circles. Through this method, learners are divided into small groups and provided with material from diverse sources, such as: textbook passages, different historical sources, oral evidences and newspaper articles. Each group examines the resources critically, with guiding questions such as:

- Whose voice is prominent and powerful in this narrative?

- Whose perspectives are missing or sidelined?

- What assumptions does this text make about power, culture or identity?

- How does this knowledge affect our understanding of society?

The groups share their reflections in a whole-class dialogue. This method inspires learners to practice critical thinking, compare different perspectives and learn together to create real meaning. For instance, in a chapter on national independence, learners could compare textbook content with community narratives of struggle or critiques of nationalist movements. By examining different narratives, this approach disrupts curricula that repeatedly reinforce powerful ideologies.

Challenges and possibilities

While Freire’s vision of emancipatory teaching is inspiring, its implementation in social studies encounters challenges. National curricula are often strongly organised, with limited space for critical questioning on state ideologies. Teachers may face institutional pressures to apply rote or traditional learning. Additionally, other stakeholders like parents or policymakers may resist critical pedagogy, observing it as politically biased.

However, Freire’s ideas remain vital, specifically because they challenge these restrictions. Even within prescribed curricula, teachers can make spaces for dialogue and critical reflection by questioning, incorporating local narratives, and by nurturing inclusive discussions. The increasing emphasis on global citizenship education and critical thinking in educational policy create openings to support Freirean practices within existing systems.

Finally, emancipatory teaching needs courage and creativity. Teachers must be equipped well to navigate the tensions between institutional demands and transformative goals, while remaining committed to empowering students as reflective and active citizens.

Conclusion

Paulo Freire’s philosophy of critical pedagogy offers lessons for teaching social studies. His critique of the banking model discloses limitations of rote, indiscriminating teaching, while his ideologies of dialogue, conscientisation and praxis provide a framework for transformative education. Integrating these principles can change the classroom from a place of indoctrination to a stage for emancipation, where learners engage with power, ideology and social realities.

Through strategies such as critical dialogue circles and counter-narrative analysis, educators can interpret Freire’s ideas into meaningful classroom processes. Despite challenges, applying Freirean pedagogy allows teachers to encourage learners to question power and develop their consciousness on societal issues in a meaningful way, making them capable of transforming oppressive set-ups. As Freire reminds us, education is never neutral: it either serves to domesticate or to liberate.