This blog was written by Sohail Ahmad, PhD student at the REAL Centre and Aga Khan University; Yusuf Sayed, REAL Centre, University of Cambridge; and Sajid Ali, Aga Khan University’s Institute for Educational Development, Pakistan (AKU-IED).

The challenges of providing equitable and high-quality education in Pakistan have been widely discussed. Reports frequently highlight alarming statistics of the education system, including the out-of-school problem, lack of infrastructural resources, and the high teacher-student ratio crisis. Encouragingly, there is a growing movement advocating for the use of data in policymaking. This makes the case, convincingly, that as more and better data exists than ever before, the focus must now be on translating this evidence into actionable educational policies through greater collaboration and capacity building. Similarly, international donors like Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) are supporting the government of Pakistan to enhance the capacity of stakeholders for data generation and utilisation for policy decisions.

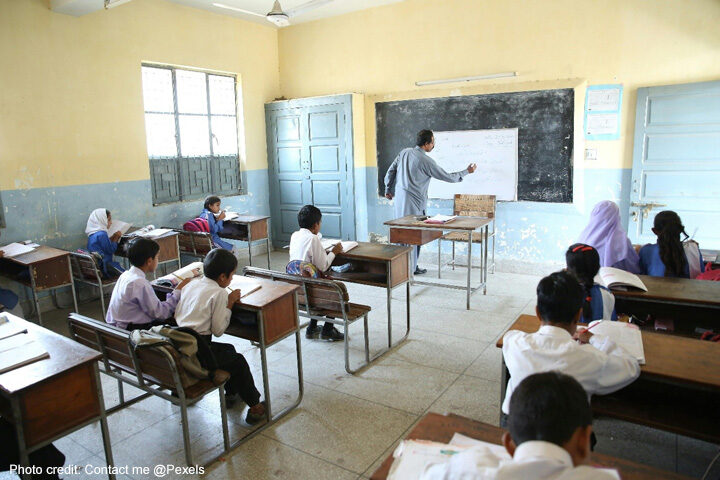

While existing reports about access, infrastructure and learning poverty are indeed sobering and essential for policy, the discourse, and consequently the data sets, still seem to be missing a vital component: understanding the work of teachers and teaching quality. In other words, the existing reports do not explicitly address the quality of teaching inside classrooms that, after learners’ home background, largely shapes student learning.

Statistics on teacher availability and student numbers tell us about inputs and ratios and learning outcome data tells us about the end result (outcomes). But what about the crucial process in between? How effective is the teaching itself? What teaching approaches are being employed? Are teachers equipped with the skills and support necessary to foster meaningful and equitable learning? Are children in marginalised communities receiving as equitable and quality teaching as those in urban centres?

These questions largely remain unanswered by the current data landscape and policy debates in Pakistan and more globally. Focusing solely on enrolment or infrastructure, or even aggregate learning outcomes, provides only a partial and one-sided understanding of quality education. Existing data on student:teacher ratios may not provide sufficient evidence for improving learning quality, as this ratio is only a proxy measure that fails to capture the complexities of effective teaching and its true impact on student learning. Therefore, more nuanced and robust data and analysis at the ‘process level’ are needed to support well-informed reform decisions.

To genuinely advance evidence-based policies that address the learning crisis and persistent inequities, we argue that existing data sets and reports must place a clear focus on teaching practices and teacher quality observed inside classrooms. This requires a systemic shift towards the regular and rigorous assessment of teaching through valid, reliable and robust classroom observation tools. Several efforts have been made in this direction including the Teach tools used by the World Bank (early childhood, primary and secondary); Science and Mathematics Instructional and Learning Outcomes (SMILO) by AKU-IED, Pakistan; The National Teacher Pedagogy Research study in South Africa by a consortium of higher education institutions; a teacher agency study between AKU-IED, AKF and Cambridge University; and teacher observation studies conducted by the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre. While these are important studies, we argue that they not adequately engage with holistically understanding pedagogy in classrooms, and in particular the teaching of values and affective dimensions of education. Moreover, we do not wish to use such measures to regulate and monitor teacher performance narrowly. Instead, we argue what is needed are teacher observation tools which are not punitive in nature but rather seek to gather concrete evidence for policy decisions on what is happening precisely where equitable and quality learning is intended to occur – in the classroom.

Generating data about teachers and teaching quality will have significant policy implications for improving teaching quality. Firstly, it will provide a true picture of equitable access to quality learning. It will shed light on whether children in marginalised communities are receiving the same quality of teaching as their wealthier counterparts. Such data will pinpoint disparities and guide targeted interventions to ensure every Pakistani child has access to a quality teacher and teaching.

Secondly, robust teaching effectiveness data will help in designing tailored, needs-based continuous professional development programmes for teachers. Instead of generic, one-size-fits-all training, we could develop programmes that address specific pedagogical weaknesses identified through observation, empowering teachers to improve their craft. Establishing a transparent and contextually-grounded system for teaching quality is imperative to support education reform and improvement across all levels of the education system, enabling policymakers, school administrators and teachers to enhance equality and quality learning. Supporting systematic observation not only acknowledges the value of teaching but also serves as a powerful incentive for professional growth, appreciating the efforts and commitments of teachers.

To realise this vision, there is a need to invest in a valid, reliable and user-friendly classroom observation tool that is not merely imposed from above but is co-developed with teachers. For any tool to be effective and trusted, it must reflect the contextual realities in which teachers work, be easy to implement without disrupting learning, and provide actionable feedback in real time. Crucially, the information gathered must be accessible to those directly involved in the process of teaching and learning – school leaders, mentors and teachers themselves – so that it informs school-level improvements as well as broader systemic reform.

As we work to improve education systems, it is important to remember that, after home background, the quality of teaching matters the most for equitable learning. Future education policies and data collection should focus not just on input or output factors, but also on what is happening inside classrooms. By closely examining teaching practices, we can make more informed decisions and ensure that every child receives the quality and equitable education they deserve.