This blog was written by Dr Susan Marango, Senior Research Associate at the REAL Centre, University of Cambridge.

This blog post provides key takeaways and insights from the panel discussion on ‘Decolonisation, climate and conflict’ at the REAL Centre’s 10th anniversary conference held on 12 June 2025. Intriguing questions and themes explored on this topic included: What does decolonising education mean? What makes climate change a wicked problem? What is the role of education in mitigating the effects of conflict? And how is it exacerbated by inequalities and conflict? How can we address climate change adaptation in education during a time of complex organisational crisis?

You can watch the panellists speaking in this video:

Decolonising education

Professor Yusuf Sayed (University of Cambridge) kicked off the discussion by defining decolonisation as a process that required confronting and undoing colonising practices. He criticised the current cutbacks on aid and development budgets globally including in the UK and the impact on climate justice and equity in and through education. And spoke to the need for reframing aid in the context of the call for reparations by colonised peoples and nations.

Yusuf Sayed highlighted the structure of educational institutions and the curriculum as key to decolonisation and challenged educational institutions to commit to decolonising education. This would involve reflecting on what knowledge should be produced, whose knowledge should be legitimate and what ways of knowing should be prioritised. He identified climate education as key to climate adaptation solutions, and to the development of climate literacy.

Yusuf Sayed spoke about the important roles that teachers play in education and the crucial role in developing in learners the competence for empathy and social justice. He also highlighted the dual role of teachers, noting how in many cases and contexts of violence and genocide teachers may be perpetuating divisions and marginalisation.

Climate change as wicked problem exacerbated by inequalities and conflict

The complexity of climate change and the urgency to address the climate crisis was unpacked, while highlighting the role of the moral and ethical dimension in climate change. The panellists identified education as a powerful and pivotal tool to stimulate and accelerate climate action and justice.

Steve Davison (Director of Strategy, Cambridge Zero) described climate change as ‘wicked’ due to its complexity and interconnectedness which makes it difficult to predict and manage its impacts. Adding that, this is exacerbated by inequalities and conflict which need to be addressed urgently, as the ‘walls are closing in.’

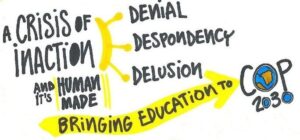

To unpack the moral and ethical dimension of climate change, Steve Davison identified the ‘3Ds’ that prevent climate action: Denial — challenging the basis for action; Despondency — wilful inaction and dereliction of responsibility; and Delusion — prompting inadequate and insufficient response to climate change.

To unpack the moral and ethical dimension of climate change, Steve Davison identified the ‘3Ds’ that prevent climate action: Denial — challenging the basis for action; Despondency — wilful inaction and dereliction of responsibility; and Delusion — prompting inadequate and insufficient response to climate change.

Despite education being undervalued in addressing climate crisis and inaction, said Steve, it is required to encourage responsibility, civic development and to navigate misinformation about climate change.

The role of education in mitigating effects of conflict and in promoting social justice

While condemning the ongoing conflict in the Middle East region, particularly in Gaza, the importance and expansion of education in emergencies over the last 25 years was highlighted and its shortcomings unpacked. Maha Shuayb (Director, Centre for Lebanese Studies) challenged academics to exercise academic freedom to address social justice.

Dr Julia Dicum (Director of Education, UNRWA) summarised UNRWA’s longstanding refugee education programmes, which have offered fully-accredited basic education and TVET to over 2.8 million Palestine refugee students living in the Middle East for over 75 years, helping them to reach their full human potential, even under the most difficult circumstances.

While she commended UNRWA and UNHCR for considering localisation and introducing refugee-led initiatives, Maha Shuayb broadly condemned humanitarian organisations for their bureaucratic and narrow project-oriented agendas. She stressed their lack of political accountability of humanitarian education to the whole society and requested for a thorough reflection by humanitarian organisations on the accountability to the communities and countries of the Global South.

While she commended UNRWA and UNHCR for considering localisation and introducing refugee-led initiatives, Maha Shuayb broadly condemned humanitarian organisations for their bureaucratic and narrow project-oriented agendas. She stressed their lack of political accountability of humanitarian education to the whole society and requested for a thorough reflection by humanitarian organisations on the accountability to the communities and countries of the Global South.

Furthermore, Maha Shuayb criticised humanitarian education agendas for being temporary, and not transformational; for focusing on access and numbers to bring more aid, not equality of outcomes; being rooted in charity, often saviourism—while real education is rooted in liberation; embedded in technical projects, and not in social justice; and for being obsessed with visibility and reporting, while communities remain invisible.

Maha Shuayb questioned the purpose of education under a humanitarian paradigm and pointed out that academics have the potential to play a significant role in constructively critiquing the system. Meanwhile, universities should rethink their role and how they engage with the communities locally and globally. Maha Shuayb demanded political action to challenge the very use of aid to sustain colonial hierarchies and social injustices.

Climate change adaptation in education amidst complex organisational crisis

Despite the compounded crises: climate change, war, displacement and fragility, which continue to put the right to education and the right to a liveable environment under threat, Julia Dicum discussed UNRWA’s commitment to promoting climate resilience by mainstreaming environmental sustainability in all its interventions, including supporting refugee education programmes.

Julia Dicum argued that climate change disproportionately affects those living in poverty, including refugee communities, and that it disrupts children’s learning and health. Palestinian refugees are among the most climate-vulnerable populations in the Middle East, living in dense urban camps, with poor water access, fragile sanitation systems, and limited infrastructure resilience.

She added that through UNRWA’s 2023 Greening Strategy for schools and vocational training centres, and solid waste management in Palestine refugee camps, UNRWA has invested in solar-powered classrooms, green building standards, and energy-efficient school facilities to reduce the carbon footprint. These activities promote awareness, creativity, and civic responsibility—essential for building a generation of climate-literate citizens.

Julia Dicum recommended the teaching of green skills in TVET for building a breadth of skills to fuel a just transition to green jobs for adaptation and resilience.

Notwithstanding the progress, climate change and environmental education is presently taking a back seat in the Middle East region due to the relentless conflict in Gaza which is contributing to the environmental catastrophe, by destroying school buildings, farmland and tree cover, while also polluting the water, thereby undermining the initiatives that promote climate change resilience.

Financial and political pressures were pinpointed by Julia Dicum as two of the major stumbling blocks for UNRWA to effectively promote and sustain basic education and TVET for Palestine refugees, and combat climate change through education.

Call to action

This panel concluded by considering policy, practice and research recommendations for tackling the interconnected challenges of climate, conflict and education. This included:

Academics and teachers

- Teachers need to be creative in teaching to re-build education, raise awareness and navigate misinformation about climate change.

- Academics are strongly encouraged to exercise academic freedom to address social justice.

Humanitarian organisations

- Humanitarian organisations need to consider long-term and transformational education.

- They need to develop theories of change for humanitarian education to address accountability.

- Organisations must consider partnerships with academia, graduate students and technical experts, to support and integrate the teaching of climate change resilience in refugee camps.

- Humanitarian organisations need to take a systematic approach to ensure the full integration of climate change resilience across all operations.

Political leaders

- The panellists demanded a just and sustainable peace in the form of a ceasefire not just in Gaza, but across the whole region. Maha Shuayb quoted from a new book on education in times of war: ‘The children of Gaza do not need peace education programmes to teach them about justice; they live it in the absence of justice. They do not need trauma interventions to name their pain; they need the world to stop inflicting it and asking them to die quietly’ (p.9).

- Political leaders must consider increasing (not cutting) and sustaining financing and budgeting for education, research and climate resilience initiatives.

To conclude the discussion, thought-provoking questions were raised by the audience, for all to ponder on: What can bring real, genuine change in education? What is social justice from a global majority perspective? How do we build individual resilience? Emergencies and humanitarianism remain in silos – What can we do about the education crisis? What is the role of the academy and academics in challenging injustice in all its form?

—–

This blog is part of a series unpicking issues discussed at the REAL Centre 10-year anniversary conference in June 2025. Others in the series include:

A decade of learning, a future of inclusion: The REAL Centre’s journey

Advancing inclusive education: Moving beyond tokenism

Elevating teachers’ voices to support equitable learning

“Where next?” Navigating a future for education and international development amid funding cuts

Great article, very informative!