This blog was written by Aditi Sehrawat, Disha Sharma, PhD scholars at Dr. B. R. Ambedkar University Delhi, India.

Global debates recognise that students’ educational achievements rely heavily on teachers’ quality, motivation, and capability. The OECD confirms that students’ wellbeing also depends on teachers’ initial education and professional development. However, the instrumental educational reforms overlook the bidirectional relational aspects between teachers’ and students’ wellbeing. While teachers undeniably shape students’ educational experiences and development, there is also a ricochet effect that exerts a significant influence on the professional and emotional wellbeing of teachers. Yet teachers’ wellbeing remains an underexplored site of inquiry in education and policy discourses. From the perspective of public school teachers in India, this blog first presents the critical issues they face. Then it argues for building mechanisms for teachers’ wellbeing by mending the systematic failures at the global and national levels.

Fragilities of Indian public school teachers

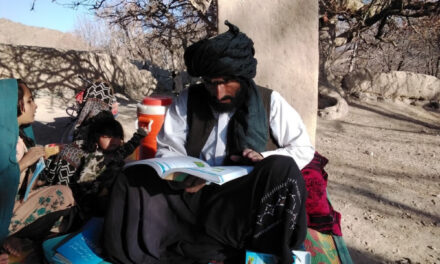

In the Indian schooling system, the question of public school teachers’ wellbeing is problematic and complex when situated within the sociocultural disjuncture between teachers and students. Indian public (government) schoolteachers are employed in severely under-resourced schools catering only to the extremely marginalised sections of the population. The life realities of these students are entrenched in poverty, caste hierarchies, gender-based discrimination, regional disparities, linguistic exclusions, and disabled-unfriendly infrastructures. The socio-economic status of these students differs significantly from the relatively privileged ‘ethnocultural’ or social backgrounds of their teachers, creating asymmetries between teachers and their clientele. This widening social distance is often reflected in teachers’ deficit perception about the educability of these marginalised students, stereotypical assumptions about them, and labelling them based on their socioeconomic and caste identities. Such experiences of exclusion and alienation in schools produce a ‘culture of fear’ in these students.

The socio-economic disparities and the emotional distress entailing their context can also have a pernicious impact on teachers as they all shape their everyday work landscape. The suboptimal working conditions of public schools, underdeveloped infrastructure, and other contextual factors additionally have a demoralising impact on teachers. The high emotional exhaustion of the job in a public school also contributes to teachers’ burnout and mitigating professional self-image. These experiences produce ‘emotional misunderstanding’ and detachment between students and teachers, further exacerbating existing inequalities. This results in fractures at both institutional and structural levels, leaving little to no space for teachers to emotionally understand their students.

The generalised character of public school teachers as ‘inefficient’ and ‘immoral’ needs to be contested, along with the pitfalls of teacher education, education policy, and political injustice carved out for teachers. The inability of teachers to connect, relate to, and understand students emanates from dominant teacher education and child-centered discourses that foster the reductionist lens and view students only by their achievements and not as an accumulation of multiple frameworks creating their context. Such discourses are subsequently unequipped to train teachers to locate education and students in the large socio-economic and cultural context, compromising the relational aspect of the teaching-learning process.

Neoliberal regimes narrate popular discourses on teachers and education policies, inducing parameters of control, performance, and subjecting accountability on teachers for students’ overall wellbeing, including mental health, but with a deprived sense of support, knowledge, and training. The weaker policy representation of teachers could be understood from their fragile political location. This is because Social problems are constructed and shaped through political, cultural, and social processes. Such processes prioritise certain issues while disregarding others, which eventually reinforces power structures within the broader teacher education milieu. Thus, selectively negating the affective labour of teachers from critical dialogues on educational issues, reinforces structural injustice against teachers while politically marginalising them.

How can teachers be supported?

For preparing teachers to address all the contextual realities, this blog argues to deploy a critical humanities approach to teachers’ policy and education discourses because teaching is a ‘relational activity’. The teaching and learning process requires a ‘heavy emotional investment’ from teachers. The ‘culture of fear’ could be addressed when emotions of both students and teachers are given their due place in the formal education setup. The centrality of emotions in educational reforms is a step that ‘acknowledges’, even ‘honours’, ‘encourages capacity-building’, and ‘shows more pride’ in teachers’ work rather than marginalising the emotional aspect of their profession. By not recognising the overlapping and interlocking nature of teachers’ mental wellbeing with their students’ context, policy frameworks do a grave political injustice. Such an unrelenting oversight not only undermines the wellbeing of teachers but also impacts the quality of teaching.

Humanising the teaching profession by shifting teachers’ mental wellbeing concerns from private realms to political frameworks would prepare a better functioning system for teachers to acknowledge students’ emotional needs, helping to mitigate the socio-emotional disconnect between them. This preparation must begin at the policy level, transcending to initial and in-service teacher education. Deploying a critical humanistic lens to education policies and discourses will soften the harsh managerial edges defining the teaching profession. The experiences of distress and marginalisation are amplified due to contentious political times caused by the recent global crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical disturbances, climate distress, and other global conflicts. That said, the need to critically build on the present arguments is escalating at the national and global levels. The systemic invisibilisation of the voices of teachers and their mental wellbeing within national policy discourses serves to silence the everyday lived experiences of teachers, along with depoliticising and diminishing the inherently structural nature of the challenges embedded in their everyday professional journeys. Even if Indian public school teachers bear the emotional and traumatic weight of the systemic inequalities faced by students, their wellbeing remains marginal both in policy discourses and institutional frameworks.

Although this blog acknowledges teachers’ position as potential agents of change for students, it also comments on the limiting factors hindering Indian public school teachers from accessing adequate support mechanisms that would focus on the emotional aspects of teaching and eventually enhance their professional development.