This blog was written by Sahar Saeed (2025 Research Fellow) and Najme Kishani (Research Manager), at PAL Network. Findings are based on the impact evaluation conducted by the Research Unit at PAL Network.

The My Village 2 impact evaluation offers important evidence on how short-term, level-based foundational learning interventions perform across different socioeconomic groups. Many of the learners who began at the lowest proficiency levels came from the poorest households. The evaluation finds that these children made substantial gains in both literacy and numeracy, narrowing down learning gaps with their counterparts from higher wealth groups, and even outpacing them in some of the foundational level.

This brief explores whether remediation models that group children by learning level, rather than age or grade, can serve as tools for equity. Drawing on descriptive and regression-based evidence from Nepal and Tanzania, it examines how household wealth shaped learning trajectories and where gaps persisted. The findings highlight that while level-based pedagogical approaches support foundational catch-up, structural inequalities still shape who advances to more complex competencies.

To move toward truly equitable outcomes, foundational learning programmes must go beyond access and ensure that disadvantaged children receive the time, support, and targeted reinforcement needed to sustain progress. Without the right support and reinforcement, the benefits of such interventions may stop short of their full potential.

- Background and context

Socioeconomic disparities in learning remain among the most persistent and under-addressed challenges in global education. While policy discussions often focus on gender and disability, the role of poverty in shaping learning outcomes is less frequently articulated in programme design or monitoring frameworks. Yet there is consistent evidence that children from low-income households are more likely to start school at a disadvantage, perform lower at their foundational literacy and numeracy skills, face higher risks of dropout, and struggle to access individualised learning support.

Standard classroom instruction, often aligned with grade-level expectations, tends to overlook these disparities. When all children are expected to keep pace with the curriculum regardless of starting point, those from the poorest households are frequently left behind.

Although interventions aimed at “low-performing” or “out- of-school” children often reach those in poverty, they rarely address the full set of structural barriers these children face, such as limited home learning environments, higher domestic burdens, or parental illiteracy.

Against this backdrop, foundational learning interventions that group children by skill level, rather than grade or age, offer a potential entry point for more equitable learning recovery. However, their ability to offset socioeconomic disadvantage depends not just on instructional design, but on whether equity is explicitly integrated into how children are identified, supported, and tracked.

- About the My Village programme

The My Village programme, led by the PAL Network, is a multi-country initiative aiming to reach one million children with foundational learning by 2027. Anchored in the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) methodology, the programme organises children by their current learning levels rather than age or grade, delivering targeted instruction in literacy and numeracy. Its design emphasises flexibility, learner-centred level-based grouping, and rapid progress through short, intensive instructional cycles informed by periodic assessments every 10-15 days.

In 2024, the second phase of the My Village programme was implemented across 35 villages in Nepal and Tanzania. The intervention combined accelerated learning camps with complementary elements such as community libraries, SMS-based parental engagement, and life skills sessions. Over 7,100 children aged 6 to 17 were assessed at baseline and endline using an adapted version of International Common Assessment of Numeracy (ICAN), and International Common Assessment of Reading (ICAR), developed by PAL Network.

The My Village model is inherently inclusive, prioritising children who are out of school or behind grade level, and it offers a strong foundation to further articulate its equity goals more explicitly in terms of poverty, gender, and disability. The programme’s entry points are performance-based. As such, it reaches many disadvantaged children by default, particularly those from the poorest households, even though it does not systematically disaggregate participation or tailor support by socioeconomic status.

- What this brief seeks to address

The impact evaluation of the My Village project provides an opportunity to examine how household wealth influences learning trajectories within a level-based, short-term intervention. While the programme did not explicitly target children from low-income households, many of the participants, particularly those who began at the lowest proficiency levels, came from the poorest quintiles. This allows for an exploration of how such learners performed, and whether the intervention contributed to narrowing learning gaps between wealth groups. This brief focuses on three interrelated questions:

- How did children from the lowest wealth quintiles progress in foundational literacy and numeracy during the learning camps?

- Did the intervention contribute to reducing learning disparities between poorer and wealthier children?

- What design considerations might strengthen the model’s responsiveness to socioeconomic disadvantage?

- Learning at the margins: Evidence from the evaluation

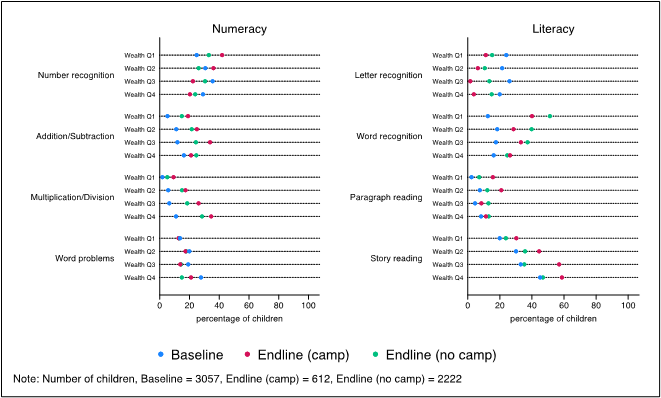

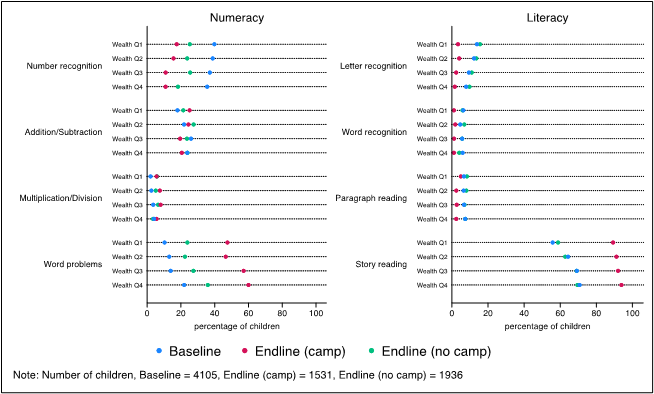

The My Village household-level questionnaire collected data on asset ownership, housing materials, and access to services, which was used to construct a wealth index via principal component analysis (PCA). Within each country, children were ranked into four wealth quartiles to allow for relative comparisons of learning outcomes by socioeconomic status. This section presents how children across these quartiles performed in the learning camps, and whether the poorest learners progressed differently than their wealthier peers.

|

|

Key findings from Nepal

- The learning camps significantly improved all children’s learning performance.

- Children from the lowest wealth quartile made the most substantial progress in both literacy and numeracy.

- In numeracy, 86 percent of children in the bottom wealth quartile advanced by at least one level, compared to 53 percent among the wealthiest. Similar patterns were found in literacy, especially at lower proficiency bands.

- Children from poorer households showed greater upward movement from beginner levels.

- By endline, children from the highest wealth quartile remained more likely to reach advanced literacy and numeracy levels, particularly story reading and comprehension.

This divergence suggests that while level-based instruction helped equalise progress at foundational levels, gaps in higher-order learning persisted. These patterns were reflected in regression findings, which showed statistically significant gains across all groups, but no significant interaction effects by wealth in the most advanced foundational skills—indicating broadly similar learning responses across socioeconomic strata, but unequal end-levels of attainment.

Key findings from Tanzania

At baseline, disparities by household wealth were evident, with children from wealthier households starting at higher literacy and numeracy levels.

- All wealth groups improved over the course of the intervention.

- Children from poorer households made notable progress in literacy—particularly in transitioning from word to paragraph reading—bringing them closer to their wealthier peers.

- In numeracy, while children across all wealth quartiles improved, relative gaps persisted, with wealthier children more likely to reach advanced levels.

- Regression analysis confirmed the positive impact of learning camps across wealth groups, with no significant differences in treatment effect by household wealth. Descriptive patterns, however, indicate that socioeconomic status continues to influence how far learners progress within a single camp cycle.

- In some cases, endline percentages at lower competency levels appear lower than baseline; this reflects children’s upward movement to higher proficiency bands rather than a decline in learning.

Taken together, the findings show that short-term, level-based interventions can facilitate catch-up for children at the lower end of the learning and wealth distribution. In both Nepal and Tanzania, poorer children improved at comparable or greater rates than their wealthier peers in foundational skills. However, they were less likely to reach advanced proficiency levels by the endline, particularly in numeracy.

- Policy implications and conclusion

The experience of My Village offers valuable lessons for designing foundational learning interventions that are both effective and equitable, particularly when equity is approached as a core design principle, not an incidental outcome.

The findings show that level-based instruction enables rapid foundational gains, especially for children from the lowest wealth quartiles. However, upward progression into more advanced skills remains uneven—particularly in numeracy—and strongly influenced by factors beyond instructional grouping.

To respond to this challenge, future iterations of foundational learning programmes should take seriously the differentiated needs of children from low-income households, not only in terms of where they start, but in how much time, support, and opportunity they require to progress. This means going beyond blanket targeting of “low performers” to ask: which learners are least likely to sustain progress—and why? Therefore, two implications follow:

- Equity must be made explicit. Programmes should articulate inclusion goals in terms of socioeconomic status and monitor participation and outcomes accordingly. This includes wealth-disaggregated tracking and community-level outreach to ensure that the poorest learners are systematically included, not just reached by default.

- One cycle may not be enough. For many disadvantaged children, a single learning cycle can improve basic skills but may be insufficient for reaching higher proficiency levels. Additional or staggered cycles, with flexible pacing and reinforcement, may be needed to support full progression.

In short, the My Village programme is already a powerful force for advancing equity, reaching children who are often left behind by conventional systems. Its potential to flourish is even greater when equity is embraced not just as an outcome of access, but as a deliberate and embedded design principle. Learners with fewer resources may need more time, reinforcement, or targeted support—and when the programme proactively builds in differentiated strategies to meet those needs, it moves from being broadly inclusive to truly transformative. With this intentional focus, My Village can close the deepest gaps, ensuring that no learner is left behind as it scales.

As concrete next steps, implementers and donors might consider piloting staggered or extended learning cycles for learners in the lowest wealth groups, and incorporating simple, context-sensitive wealth-tracking modules into future programme monitoring. These measures can ensure that progress isn’t just possible—but sustained and equitable for every child.