This blog was written by Dr Dawit Tibebu Tiruneh, Senior Research Associate, REAL Centre, University of Cambridge.

On 12 June 2025, researchers, policy actors, educators and practitioners gathered at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, to celebrate the REAL Centre’s 10th anniversary at a conference, themed “Tackling Injustices in and through Education.” Among the series of discussions, one panel explored the topic: “Teachers at the Centre of Equitable Learning.”

You can watch the panel discussion here:

The panel recognised that teachers are at the heart of the learning process and central to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4: inclusive and equitable quality education for all. Four panellists reflected on key achievements and ongoing challenges in ensuring teachers can support equitable learning. Drawing on their research and professional experiences, the panellists highlighted progress on policy commitments to equity, teacher professional development (TPD), the role of teachers as evidence generators and change agents, and the importance of teacher voice in shaping decisions.

The panel recognised that teachers are at the heart of the learning process and central to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4: inclusive and equitable quality education for all. Four panellists reflected on key achievements and ongoing challenges in ensuring teachers can support equitable learning. Drawing on their research and professional experiences, the panellists highlighted progress on policy commitments to equity, teacher professional development (TPD), the role of teachers as evidence generators and change agents, and the importance of teacher voice in shaping decisions.

Policy progress on equity

A key achievement noted by the panel was the growing recognition among policymakers, particularly in low-income countries, that equity must be a priority if teachers are to play a meaningful role in classrooms. This commitment has been reflected in several national education reforms across the Global South.

Rona Bronwin, Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, pointed to a decade of rigorous research, including RISE Ethiopia, What Works Hub, and EdTech Hub, which has generated valuable insights into equitable learning. She emphasised that long-term, multidisciplinary, policy-relevant research has been vital in shaping education reforms and strengthening the link between evidence and practice, with the REAL Centre playing a leading role. Such research has informed pedagogical approaches, such as structured pedagogy, Teaching at the Right Level, and gender- and disability-responsive teaching. It has also encouraged a broader view of learning outcomes that incorporated socioemotional and cognitive skills. Progress was noted in supporting marginalised groups who face multiple disadvantages, such as girls from rural poor households who live in conflict-affected areas.

Drawing on the RISE Ethiopia programme, Dawit Tibebu Tiruneh, University of Cambridge, reflected on promising reforms: the expansion of pre-primary education in public schools (which has improved children’s readiness for school), the establishment of Inclusive Education Resource Centres (particularly in disadvantaged areas), and the expansion of gender clubs offering safe spaces for girls to discuss issues important to them and their education. These initiatives, though still a work in progress, were described as promising steps towards greater equity.

Teachers as catalysts for systemic reform

The panel agreed that quality teaching is one of the most powerful drivers for equitable learning. Baela Jamil, Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (ITA), shared insights from the ITA programme in Pakistan, which adopts a holistic teacher-centred approach to improving equitable learning. Their experience showed that sustainable change requires whole-system reform with teachers at the centre.

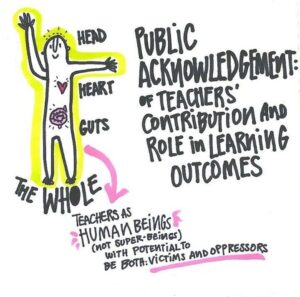

The example of “A Journey of Happiness”, a summer school initiative, illustrated how project-based, creative learning rebuilt teachers’ confidence and shifted perceptions from failure to potential. Drawing on her research and advocacy experiences, Baela Jamil argued that teachers must be seen not only as knowledge deliverers but also as mentors, counsellors, therapist and evidence generators who bring social and emotional care into the classrooms. Recognising teachers as whole persons (social, emotional and academic actors) was described as vital to placing them at the centre of reform as trusted, empowered and humanised professionals.

The example of “A Journey of Happiness”, a summer school initiative, illustrated how project-based, creative learning rebuilt teachers’ confidence and shifted perceptions from failure to potential. Drawing on her research and advocacy experiences, Baela Jamil argued that teachers must be seen not only as knowledge deliverers but also as mentors, counsellors, therapist and evidence generators who bring social and emotional care into the classrooms. Recognising teachers as whole persons (social, emotional and academic actors) was described as vital to placing them at the centre of reform as trusted, empowered and humanised professionals.

Bringing data back to teachers

Lydie Shima, Laterite Rwanda, drew on the Leaders in Teaching Rwanda programme, which piloted participatory research dissemination workshops. Teachers were presented with findings on inequities in learning outcomes, gender disparities in school leadership, and effective teaching practices. They were then invited to reflect on the evidence, identify causes and propose policy recommendations.

This approach deliberately positioned teachers as interpreters of evidence, not just research subjects. Their reflections shaped policy briefs and fed into national policy discussions, helping bridge the gap between research and practice. Teachers’ involvement shifted dynamics from top-down to participatory; and informed reforms in TPD, curriculum and gender-responsive mentorship. Importantly, it also built trust in research and encouraged teachers to engage in future initiatives. The REAL Centre, working with Laterite Rwanda, was recognised as a key partner in this exemplary work.

Despite progress, panellists identified persistent challenges that hinder teachers’ ability to promote equitable learning.

Teacher shortages and poor working conditions

Citing the recent UNESCO Global Report on Teachers, Rona Bronwin noted that acute teacher shortages, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, compounded by rapidly growing student populations, is a major challenge. Poor working conditions, including low and irregular pay, lack of basic teaching resources, and limited professional development opportunities, further undermine teachers’ ability to support equitable learning. Schools in many low-income countries remain severely underfunded. In Ethiopia, for example, per-student spending is among the lowest in sub-Saharan Africa, as noted by Dawit Tibebu Tiruneh.

Gaps in teacher professional development

The design and delivery of TPD programmes was identified as a major concern. Too often, TPD initiatives are centrally designed with a “deficit lens” that blames teachers for the learning crisis. Dawit Tibebu Tiruneh called this as a “misdiagnosis”, noting that systemic underfunding and socio-economic inequalities are equally significant drivers. As a result, teachers face a wave of generic, top-down TPD training that lacks relevance to local contexts and creates intervention fatigue.

Panellists stressed the need to restore teacher agency by involving them as co-creators of TPD. They also highlighted the current TPD programmes largely focus on content and pedagogy while neglecting teacher mental wellbeing and resilience, despite many working in conflict-affected and unstable environments. Supporting teacher wellbeing and resilience is therefore critical for enabling them to support equitable learning in the classroom.

Lack of institutionalised mechanisms for teacher participation

Another challenge identified was the limited formal mechanisms for embedding teacher voice in decision-making. While some initiatives have created opportunities, teacher engagement is often ad hoc rather than systematic. Panellists argued that teachers should be integrated into alliances and networks (for example, PAL Network, Teachers Without Frontiers) that shape reforms and influence governments. Engagement should not be one-off consultation but an institutionalised commitment to shared decision-making. Teacher unions, associations and learning teams should be treated as partners in reform, with governments recognising and trusting their contributions. The panellists emphasised that equity in learning requires a reciprocal process: teachers are supported by policy, and policy and programme design is strengthened by teachers’ lived experience.

Moving forward: Building on progress and addressing challenges

In closing, the panellists reflected on encouraging policy shifts over the past decade that have supported equitable learning. Visible changes include improved teacher attendance, greater use of hybrid teaching and increased public recognition of teachers’ vital roles. The COVID-19 pandemic, despite its disruptions, also yielded unexpected dividends, such as increased government trust in teachers’ ability to deliver remote learning and broader access to digital tools. However, much more is needed to address deep-rooted challenges and ensure that all teachers are equipped, empowered and supported to deliver equitable learning for every child. The panel concluded that we need a clearer vision of the “new teacher” who is resilient, creative and equity-driven, and positioned at the centre of education reform to ensure that all children, regardless of background, can learn and thrive.

—–

This blog is part of a series unpicking issues discussed at the REAL Centre 10-year anniversary conference in June 2025. Others in the series include:

A decade of learning, a future of inclusion: The REAL Centre’s journey

The role of education in decolonisation, climate and conflict: A call to action

Advancing inclusive education: Moving beyond tokenism

“Where next?” Navigating a future for education and international development amid funding cuts

Teachers’ voice matter! Thank you very much Dr. Dawit for your reflection.