This blog was written by Shaheena Salim Jumani-Alwani, MPhil Scholar at Aga Khan University Institute for Educational Development, Alumni Aga Khan University School of Nursing & Midwifery and University of the West of Scotland.

This blog discusses the question: Why does technical and vocational education and training (TVET) remain unattractive to Pakistani youth despite a shortage of skilled labour, and what lessons can be drawn from China, Russia, India, Indonesia and Germany to inform more effective reforms?

Historical developments reveal how socio-political dynamics shape TVET. The TVET field is more diverse than general education, encompassing different organisational policies, curricula, actors and regulatory modes across countries. This diversity is reflected in varied terminologies such as TVET, further education and training, apprenticeship, career and technical education. As a result, international comparative TVET research faces methodological and organisational challenges, making the production of transparent and comparable findings especially challenging. In Pakistan, rationale for TVET policy was economic growth and social stability. A doubling youth population demands productive employment, while overseas labour markets require certified skills. With most workers trained informally; formal skills can boost productivity, mobility and integration into the economy. Global perspectives across the six countries highlight several thematic comparisons.

Social perceptions and prestige

Cross-country analysis reveals how cultural esteem drives systemic success or failure. Pakistan highlights not only problems (stigma, informal dominance), but also several reform attempts. It reflects a different trajectory – despite the establishment of technical, polytechnic and vocational institutes, TVET remains peripheral to mainstream education. Academic bias in Pakistani society views higher education as equated with prestige and social mobility, contributing to the neglect of vocational tracks. This is compounded by weak policy continuity, underfunding and minimal market collaboration, and shaped by cultural values and labour market structures. Pakistan and India consider it as a ‘second-best track/last-resort’ for weaker students, and vocational education remains secondary to academic prestige, with families placing higher value on university degrees. In Germany, in contrast, employers and unions co-design curricula, ensuring market alignment. Indonesia, China and Russia demonstrate stronger state-led reforms – yet esteem is not a by-product, but an embedded design feature of systems.

Indonesia expanded TVET to meet industrial needs, yet struggles with stigma, similar to India and Pakistan. Despite reforms, vocational routes remain linked to low wages and status. China and Russia show mixed patterns with state investment raising TVET’s profile, though academic routes remain more prestigious, and post-Soviet transitions reduced its former esteem respectively in both countries.

Competence and quality of curriculum

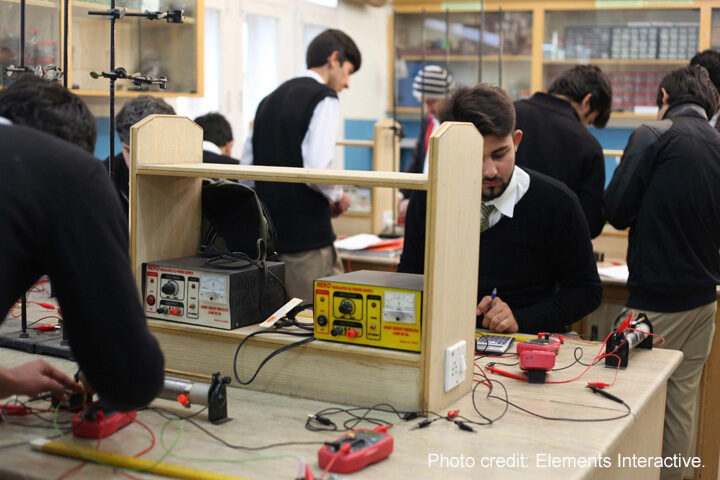

Comparative frameworks are essential for evaluating systems structure. An international comparative instrument stresses competence-based design, workplace learning and adaptability. Curriculum is divided into ‘intended’ and ‘implemented’, with qualitative analysis, structured classroom observations and teacher voice. These features appear successful in Germany, where vocational graduates are highly employable. India’s contextualised frameworks safeguard institutional effectiveness, but reflect weak employer-participation, often reinforcing social stratification. Pakistani curricula remains outdated, overly theoretical, and disconnected from labour-market realities. Global frameworks will now assess vocational competencies, recognising the role of applied-skills. Policies to integrate TVET in India aim to overcome social-status hierarchy by including TVET into mainstream education. Their policy calls for subject flexibility at secondary level, allowing students to choose from academic, physical education, arts and vocational-skills to shape their study and career paths.

Comparing how Russia, China and German include national experts’ voices suggests a similar approach could be employed for Pakistan. Qualification profiles are put forward with assessment measurements aligned to professional standards and training. Successful systems integrate three critical dimensions: workplace learning (meaningful engagement in real contexts), competence-based design (knowledge, skills and attitudes), and adaptable curriculum, incorporating market challenges. The competence-based approach, widely adopted in Europe, China and Russia, bridges education and work-applied learning, reflection and lifelong learning competencies. On the contrary, Pakistan’s curricula rarely integrate soft skills, entrepreneurship and technological adaptation, which further discourages students who perceive limited returns on vocational qualifications. Moreover, the Center for Occupational Research and Development-US, listed English, decision-making, critical thinking, inter-personal communication, ethics and computer literacy in the curriculum.

Linkages between trainees, academia, employers and industry are essential for aligning skills with the labour market. Job fair platforms and networking would help Pakistan enhance entrepreneurship, boost the image of blue-collar jobs, and support career development.

Comparison with Germany, which serves as a benchmark, indicates that strong links with companies ensures employability. Germany blends 70% workplace training with 30% classroom study for 2-3 years for over half of youth, enabling mobility, awarding qualifications, enhancing regulation with employer input, and ensuring flexible pathways exams and technician programmes. Similarly, Indonesian reforms in 2012 introduced the National Qualification Framework, promoting multi entry and exit options to use a credit system for measuring achievement. Further, a state-certified nursing-assistant programme offered for 36 months is regulated. Unlike Pakistan’s fragmented governance, and weak upward mobility pathways, Germany’s employer-led system sustains youth trust. In Pakistan, an informal apprenticeship system is often considered a means to exploit young people because of unregulated and sub-standard curricula or certifications, offering limited mobility and little formal recognition.

Interestingly, China plans major investments in Africa’s vocational sector, including industrial parks, regional centres and vocational schools. Its commitment involves training 200,000 technicians and providing 40,000 Africans with training in China. With sustained partnership in African development, the Chinese government is providing avenues for market linkages

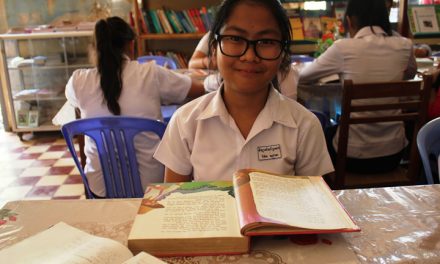

Moreover, India trained over 300 health-volunteers from tribal areas of Gudalur as nursing assistants, pharmacy, technicians and office accountants, similar to Indonesia’s 1970 reform for improving community health, family planning and agricultural practices.

Cultural and economic aspirations

Indonesian vocational education paradigms reflect a shift from a state-centric, supply-driven model to a demand-driven, competency-based framework aligning needs. The old paradigm emphasised unilateral decision-making, and programme-oriented schooling, which often disregarded learners’ prior competencies and economic realities. In contrast, the new paradigm situates TVET within a tripartite nexus of government, business/industry and community; stressing adaptability, lifelong recognition of skills and alignment with industrial culture. This transition reflects broader global TVET discourses that focus flexibility, efficiency and productivity; positioning TVET as not only educational but also a socio-economic institution, which nurtures innovation, equity and sustainability. This is similar to China and Germany, whose economic aspirations are well-established.

India has an ongoing struggle to adapt to global standards. Russia once awarded TVET a high status, but similar to Indonesia, this has faced decline with changing economies. In contrast, China, through heavy state-investment, has modernised TVET, linking it to industrial upgrading and improved status. India is focusing on certification and industry partnerships. Germany’s Education Chains initiative (2010) and reforms (2013) boosted all-day schooling, vocational pathways, disadvantaged student support, and raised students’ participation in 2016.

Involvement in vocational secondary education remains stagnant for both genders in Pakistan, far below the 10-20 % levels seen Germany and Indonesia. This depicts a persistent gap in providing alternative, skills-oriented pathways for youth. Also, China’s upper secondary enrolment exceeds India’s by nearly seven times; this seems to be driven by contextual realities and population size. Notably, cross-country comparisons must consider methodological differences for accuracy, by keeping abreast of centralised and decentralised resource distributions, power dynamics and territorial confinements.

Limitations and future directions

Pakistan’s TVET sector remains unattractive to youth due to weak federal-provincial coordination, improper regulations, academic bias, and lack of funding. Structural shifts could change this trajectory, for instance, by devolving governance to provinces, and embedding TVET in green and digital economies. The absence of capacity-building systems for trainers reflects deeper the structural neglect of human capital alongside reduced teacher attrition. Trainer and assessor development and recognition of prior learning systems are a way forward to addressing capacity gaps and reframing TVET as a credible development pathway. These directions are reflected through a political economy lens, where governance, funding and recognition reflect ongoing struggles between state, market and society.

At a theoretical level, this analysis affirms that TVET cannot be understood solely through human capital metrics of growth. Rather, capability and political economy approaches show that cultural esteem, governance models and historical legacies mediate how vocational pathways are valued with deeper determinants. Germany withstands a benchmark of excellence, while Pakistan illustrates the costs of neglect, alongside hope for transformation. China and Russia show potential with state investment, and Indonesia blends historical legacies with community partnerships. This offers lessons on policy continuity and competence-based adaptation embedded in contextual frameworks.