This post was written by Sharon Tao, Director of Level The Field. This blog was first published on the Level the Field website on 11 September 2025.

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, we discussed findings from the Third Annual G7 Global Objectives Report, which tracks progress against the G7’s 2021 commitment to get 40 million more girls into school and 20 million more reading by 2026. This post focuses on what the Global Objectives data reveal – and fail to reveal – about girls’ access and learning in crisis contexts, and what must be done to get progress back on track.

Global Objective One: 40 million more girls in school

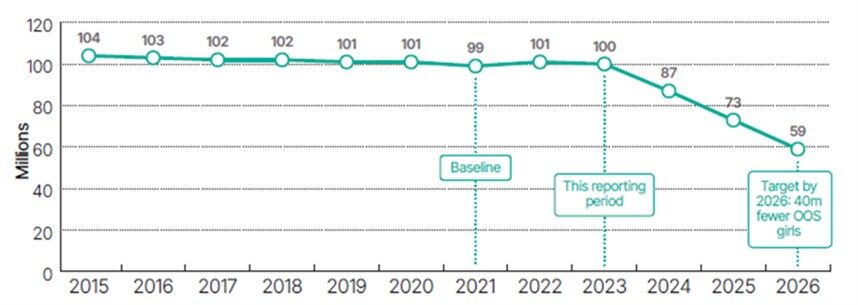

In 2021, the G7 recognised that the most marginalised girls are often left farthest behind. The first Global Objective, therefore, focuses on getting 40 million girls who have dropped out or never enrolled into school. Unfortunately, progress is far off track. In 2023 – the reporting period for this review – the global population of out-of-school (OOS) girls in 75 focal countries fell by just 1 million, a modest improvement after the previous year’s increase caused by the Taliban’s takeover in Afghanistan (see figure 1). Yet 100 million girls remain OOS, above the 2021 baseline. To reach the target, 13.6 million girls would need to enrol each year.

Figure 1. Historical and forward-looking trajectories for this Objective

Where OOS numbers are concentrated

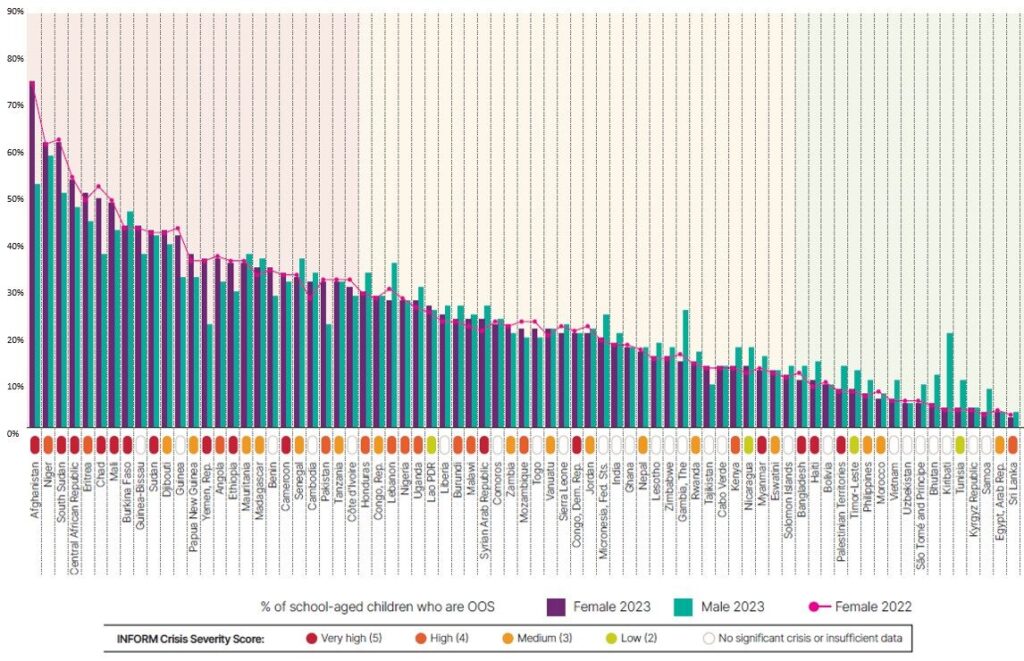

Four countries – India, Pakistan, Nigeria and Ethiopia – account for nearly half of all OOS girls. Halving the OOS population in just these four would return 24 million girls to education, covering more than half of this Objective’s target. At the same time, 9 of the 12 countries with between 40-75% of school-aged girls not in school, were experiencing severe crises (see figure 2). Crises exacerbate harmful gender norms, which results in these percentages, as well as the gender gaps in favour of boys. In some cases, these norms also exclude mothers from labour markets, thereby putting pressure on boys to drop out to supplement family incomes. This points to the need to ensure that education in emergencies and protracted crises (EiEPC) programming advances gender inequality in, around and through education.

Figure 2. OOS rates in relation to differing degrees of crisis

Hidden OOS numbers

Unfortunately, the figure of 100 million OOS girls is almost certainly an underestimate. That’s because OOS data rely on MoE enrolment records, censuses, and household surveys, which are often incomplete in crisis contexts. For example, Somalia was excluded due to missing administrative data, though estimates suggest 1.8 million girls were OOS. Since the publication of this report, UIS has updated its 2023 dataset to include Somalia, which is a welcome step. In parallel, the Education Data and Statistics Commission has convened a Task Force to guide how OOS estimates in crisis contexts can be better adjusted at both country and global levels.

Global Objective Two: 20 million more girls reading

The second Objective is also off track, and gaps in global data again obscure the full picture, especially in crisis contexts. The 2021 baseline – 74 million girls reading at the end of primary – is based on just 33 of 75 countries with available reading data. This figure has not changed for two years and cross-national assessments are a key barrier because they are conducted in limited countries, every 3–6 years, making it difficult to track annual progress. Even with the 74 million baseline, an increase of 6.6 million girls per year would be required to reach the target – another difficult prospect given the issues highlighted below.

Invisible learners in crisis contexts

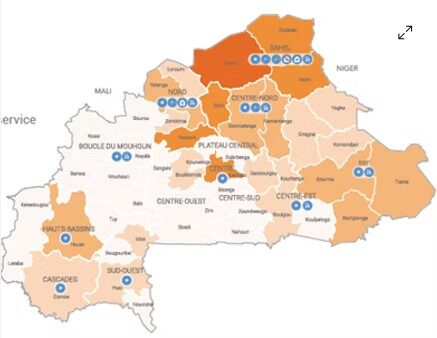

The reading proficiency of children in conflict-affected areas is difficult to ascertain because cross-national assessments are only administered in schools that are open and accessible. For example, in Burkina Faso in 2019, many schools were closed due to conflict (see figure 3). Thus, the PASEC assessment conducted that year likely excluded these children entirely. National proficiency scores, therefore, paint an optimistic picture as they miss children in conflict zones where learning outcomes are likely worst.

Figure 3. Conflict areas in Burkina Faso where children likely did not participate in PASEC

Language matters

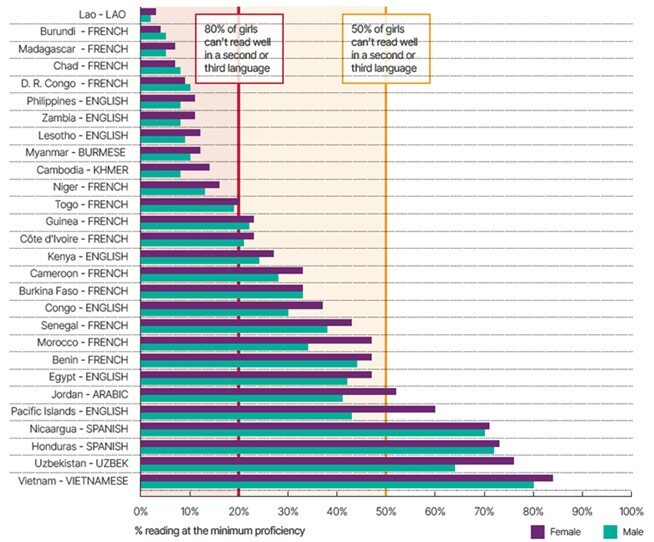

In 22 of the countries with reading data, less than 50% of girls and boys met the minimum reading proficiency level at the end of primary (see figure 4). This means over half of children left primary school unable to read. Yet these results largely reflect proficiency in a second or third language — as assessments are often conducted in English, French or Spanish. This means that reading rates for children’s first language may be better than what is reported, suggesting cross-national assessments underestimate actual reading ability. This points to the need to supplement assessments with additional data sources to provide a more complete picture of who is/isn’t reading.

Figure 4. Minimum proficiency in a second or third language

Additional ways crisis skews what is counted

It is clear that operational limitations in data collection routinely exclude children in crisis contexts from OOS and reading data. Definitional limitations also play a role: what counts as “school” or “education” is often too narrow. For example, non-formal education (NFE) – often delivered by Education Cluster partners – can include Accelerated Education Programmes, which align with ministry curricula and aim to return children to school. However, these enrolments are not captured by ministry data – and by extension UIS, SDG and Global Objectives data – firstly because EMIS systems may be compromised, but primarily because NFE is not considered part of the formal school system. This means that any educational gains made through these programmes are overlooked, which points to the need to reconsider how we define ‘education’, particularly if we want to acknowledge education in crisis contexts.

That said, whilst Education Cluster partners do collect data on the reach of NFE programming, definitions of “reach” vary, and data across partners are fragmented, making integration with global datasets difficult. Without more systematic monitoring, the impact of EiEPC investments remains undercounted.

Conclusion

The Global Objectives were designed to accelerate progress on girls’ education. Yet three years on, both are significantly off track. The Report’s recommendations point to clear priorities:

- Support EiEPC programming that advances gender equality in, around and through education.

- Prioritise Education Data and Statistics Commission Task Force work to adjust global-level data to include OOS children in EiEPC contexts.

- Go beyond cross-national reading assessments by incorporating additional data sources to more clearly capture who is/isn’t reading.

- Invest in better monitoring of the impact of EiEPC investments across humanitarian and development programming and improve the definition of the term ‘reach’.

- Advocate for recognition of NFE within definitions of ‘education’, so that the most marginalised children to whom NFE caters, are visible within education planning, budgeting and monitoring.

Above all, continued G7 engagement with the Global Objectives is critical. Although G7 partners have experienced significant changes over the past months, they still retain notable social and political capital to influence ministries, donors and other actors to align with the Global Objectives, so that ownership reaches far beyond the G7. This is the least that could and should be accomplished, to honour a commitment made in 2021, to give millions of marginalised girls a chance to learn.