This article was written by Abdirazak Haybe, Education Columnist based in Jigjiga, Somali Region of Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian government has introduced a comprehensive education reform known as the Ethiopia Education Development Road Map (2018-2031). This initiative is critical to the country’s overarching transformation strategy to enhance economic and social infrastructure. It focuses on increasing investments in education, health, and other essential services to support the disadvantaged and marginalised population.

Despite the comprehensive education reform and other initiatives, the Somali Region of Ethiopia has been grappling with a set of unique and severe challenges. These challenges, including famine, violence, pandemics, conflict, and climate-induced crises, have significantly impeded the realisation and attainment of the country’s extended strategic plan. The rise in climate-induced crises and conflicts has led to large-scale internal displacements throughout Ethiopia. During 2015-2018, the country experienced massive internal displacement induced by the complex emergency (drought, flooding, and conflict). Across the country, more than 3 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) registered at different camps. The Somali Region accommodated and hosted the largest number of IDPs, and one of the largest displacement camps emerged (named locally as Qoliji), hosting more than 80,000 households. The plight of IDPs persevered in many parts of the region, and most of the displacement camps remained protracted, devoid of sustainable solutions. An estimated 1 million children remained out of school, 527,000 of them girls, and 728 schools have been damaged by conflict and natural disasters.

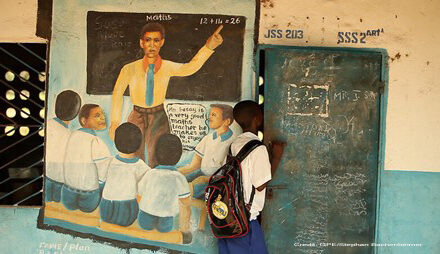

The absence of learning spaces, shortages of gender-sensitive WASH facilities, non-availability of school feeding, and shortage of basic education materials were the principal barriers that prevented emergency-affected children from attending educational services. The protracted crisis in the IDP camps of the region compelled thousands of schoolchildren to remain out of school with uncertain futures, and parents’ prospects of sending their children to school did not materialise. The region’s access to primary education has steadily increased, but the drop-out rate and gender disparity have remained high. In addition, despite early childhood education (ECE) being the cornerstone of children’s foundational learning, the gross enrolment rate in 2017/18 was only 4.5% of 4-6-year-old children in the Somali Region. Comprehensive school infrastructures, including water, gender-segregated latrines, inclusive pedagogy, relevant curriculum, and adequate teachers and child-centered instructional approaches, are critical determinants of children’s enrolment, transition, and accomplishment in their education.

Overview of Multi-Year Resilience Programme

Education Cannot Wait (ECW) has funded the Multi-Year Resilience Programme (MYRP) – a global fund for education in emergencies (EiE) and protracted crises, aimed at supporting and protecting holistic learning outcomes so no one is left behind. Before the ECW fund, financing EiE and protracted cases was not prioritised by donors. Hence, EiE is not considered a life-saving intervention. The dramatic increase of crisis-displaced children, funding constraints, limited local government capacities, strained social services, and limited economic and infrastructure development critically undermined timely responsive intervention for crisis-displaced children.

On 14 February, 2020, Education Cannot Wait announced the flagship of MYRP in three regional states of Ethiopia – Somali, Oromia and Amhara. The programme boasted a substantial budget of USD 27 million in seed funding for three years. With its resilience and determination, the Somali Region has been allocated 53% of the total allocation/fund. This budget encompasses the implementation costs, consortium, and grantee allocations, which are earmarked for national and sub-national education cluster coordination alongside emergency and refugee response initiatives. Adopting a consortium approach, the project was spearheaded by Save the Children International (SCI) in collaboration with implementing partners Organization for Welfare Development In Action (OWDA) and Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). In the Somali Region, the project targeted eight districts and 43 schools ravaged by climate-induced and artificial disasters; the project has been instrumental in making significant strides toward providing children with access to a secure, fair, inclusive, equitable, and quality education. The active role of the Somali Region in the project, from planning to execution, is a source of pride and involvement for all stakeholders.

MYRP major achievements

The MYRP has contributed substantially to improving access constraints and delivering and equipping crisis-affected children with quality and equitable education in the project intervention schools. During the three years of project implementation, the project emphasised equitable access to safe, protective, and conducive (pre-primary and primary) learning environments for emergency-affected girls, boys and children with disabilities (CWDs). The project has achieved significant milestones in improving access to education for crisis-affected children, including the construction of learning spaces, rehabilitation of schools, and provision of instructional materials. These achievements, along with the integration of out-of-school girls and boys into learning centres, demonstrate the impressive progress and impact of the MYRP in addressing the challenges in the Somali Region of Ethiopia.

Improved children’s access, protection, and wellbeing were paramount to the project intervention strategy. The project constructed 43 semi-permanent learning spaces (86 classrooms) and rehabilitated 83 schools equipped with age-relevant combined desks and other instructional materials to mitigate the access constraints preventing crisis-affected children from enrolling and continuing their learning. In addition, the pre-existing poor school infrastructure hampering the delivery of a decent teaching-learning process was enhanced through the construction and rehabilitation of 43 water points and the creation of 43 gender-segregated latrines – this contributed to the improvement of girls’ participation and enrolment in the schools. Despite the project removing access constraints of the crisis-affected children, bringing children back to school was quite challenging, and it was feared children would be exposed to risks if not enrolled in the school. Subsequently, the project conducted a community-based, gender-sensitive, and inclusive enrolment campaign across the target schools. Children’s enrolment and retention enormously improved through the provision of assorted support, including scholastic materials and catering of school feeding (hot meals) that enabled the retention of 39,431 of the crisis-affected children (18,900 girls), which exceeding the initial project target (32,210). Despite this, barriers to education for CWDs persisted significantly. Inclusive education supporting CWDs was created after the project conducted vulnerability mapping for in- and out-of-school children using Special Needs Action Packages and the Washington Groups of Questions, and their needs were addressed. Besides this, community-based pre-primaries were piloted and rolled out to increase school readiness and prioritise the participation of out-of-school children, girls, and CWDs. At the same time, cash support was injected into 106 vulnerable mothers from the project intervention districts to generate income sustainably to cover food and other family costs, including education-related expenses of their children.

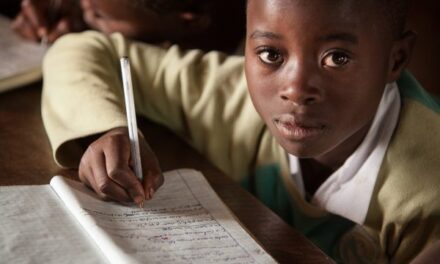

In crisis contexts, the delivery of quality and relevant education to children is compromised; teachers need the minimum learning competency to deliver lessons, resulting in children not mastering foundational skills. Accordingly, addressing the quality and relevance of education for emergency-affected children, girls, and CWDs is enhanced through undertaking school-based gender-sensitive and inclusive assessments of children’s competencies, appropriate instructional methods and school leadership training. Literacy and numeracy intervention was prioritised, and children’s foundational skills improved through community reading awareness and established reading corners with the support of supplementary reading materials. However, teachers required complementary skills outside the regular teaching to support children; more than 1,622 schoolteachers, cluster supervisors, school directors, and PTAs (456 female) were provided with assorted capacity-building training, including school management, mentoring, coaching, supportive supervision, instructional methods, continuous assessment, and peer support, along with wellbeing system, literacy, and numeracy training. In addition, rapid response teams were established in all schools and trained in fast response to strengthen their capacity for rapid emergency response.

Furthermore, retention and transition for emergency-affected girls and boys, including CWDs, were boosted through remedial class sessions aimed at improving the academic achievements of low-performing children, and more than 4,200 children (1,860 girls) benefited and better transitioned to the next level of their learning. The project purchased tablets uploaded with age-relevant supplementary reading materials adapted to the local language and distributed to target schools in the camps to enhance children’s reading skills. Refugee inclusion was also prioritised and supported, and 223 refugee teachers were provided with scholarships to upgrade their education levels to certificate and diploma levels. 158 teachers (109 male, 49 female) graduated with a diploma, and 65 teachers (34 male, 31 female) graduated at the certificate level.

The capacity of education cluster coordination was strengthened by building national and subnational education cluster coordination capacity systems and technically supporting the education information management system by assigning experts. Likewise, it enhanced the gender-sensitive education system by revising the gender-sensitive education cluster strategy at the national level. It strengthened gender-sensitive EiE data collection, management, and dissemination at the education cluster.

The effects of the MYRP on children’s learning

- The programme has improved the learning environment and increased access and transition for emergency-affected boys, girls, and CWDs. Improved learning performance of pre- and primary school children due to training of teachers and improved learning environment. Saving and credit schemes provided to poor mothers helped to improve their livelihood and help their children continue their education.

- The average attendance rate among students climbed to an impressive 95%, which reflects a mere 5% drop-out rate. This figure is notably lower than the national average of 13.2% and the regional average of 6.6%, underscoring the project’s impact on educational attainment.

- Gender parity achievement in the programme area is promising and has been registered at 0.94, while regional gender parity is at 0.77, far below the national average (0.91).

- The provision of school feeding attracted children to school (enrolment), helped to reduce dropouts, boosted regular attendance, and alleviated temporary hunger.

- The assorted and well-structured capacity building helped to build a sense of ownership and empowerment. In addition, the government structures and the community gained greater control over their development, enhancing their ability to envision and take better positive action.

- 4% of Grade 3 students in the MYRP intervention areas in the Somali Region correctly identified letters, implying that about 24.6% are non-readers. This indicates that children’s foundational reading skills improved substantially, much better than the national average of 32.9. This points out that the impact brought about by MYRP is twofold when compared against the country-wide average.

- The interaction in the teaching-learning process is improved due to the training provided to teachers and teaching materials provided to schools. The combined effects of inputs, methods, and outputs enhanced the practical realisation of the quality and relevance of education for emergency-affected girls and boys, including CWDs.

- The project end-line assessment revealed that 80.7% of Grade 3 students in project-supported schools in the Somali Region have identified numbers. Being able to recognise and automatically name numbers (number identification) visually is a skill that every student should develop, as this will help them improve their number skills and ability in math. Number recognition is a vital skill that students need in their everyday lives.

- About 70.4% of Grade 3 students can discriminate numbers, indicating which are big or small. Recognising numbers helps children understand math concepts, which allows them build confidence in mathematics.

- About 66.4% and 62.3% of Grade 3 students have developed the ability to do essential addition and subtraction respectively, as set for their grade level. This performance reveals that most students can perform operations that involve combining objects into a more extensive collection and finding differences between numbers or quantities.

- The alternative learning programme, remedial classes, or tutorial sessions ensured the continuation of enrolment for out-of-school children and vulnerable learners. It improved the performance of low-performing children who missed their class since persistent poor quality of teaching and lack of parental support at home undermined the children’s performance.

- The drop-out and repetition rates are less than 5% in most grade levels, implying high primary school retention and transition rates in MYRP-supported schools. Several programme intervention activities, such as improved school infrastructure and WASH facilities, provision of educational materials, teachers and PTA capacity building enhanced learning readiness, monitoring and evaluation of schools, may have contributed to improved school system efficiency (fewer wastages and more retention). The findings revealed that the longer the intervention (the more MYRP duration), the lesser the drop-out and repetition rate, confirming the programme’s effectiveness.

- Survival rates showcased 79.7%, indicating a high retention level and a low incidence of dropouts. This shows the program’s effectiveness when compared against the national average of about 52%. The teacher’s application and practice of interactive teaching methodology improved children’s learning performance. (ECW-MYRP Final Evaluation – Final Version (002)

Conclusion

MYRP interventions increased equitable access to safe, protective, and gender-sensitive learning environments and enhanced quality and relevance for emergency-affected girls and boys, including CWDs. Besides this, the project created access to 39,431 vulnerable children (18,900 girls) in the Somali Region and improved learning performance (enabled about 60% of Grade 3 students to read and 66.4% to do simple addition related to their level.) There has been a high retention rate (over 95%), and the programme activities helped to solve barriers to education, implying the programme was effective, relevant, and efficiently implemented. The MYRP was aligned with national education policies and priorities, such as the National Education and Training Policy (2023), Education Sector Development Programs (ESDP VI), Ethiopian Education Development Roadmap (2018-2030), SDGs, minimum educational standards and priorities. The tremendous achievements made by the MYRP project should be maintained and replicated in its best practices and lessons learned for future education project implementation. The MYRP per child cost was inspiring and impressive, as the price per child indicated USD 84.90, which is lower than the World Bank education expenditure per child of primary education age in Ethiopia, which indicated USD 121.

The World Bank stated, “90 percent of children in Ethiopia at late primary age are not proficient in reading indicated inefficiency though 121 USD is spent per child. The World Bank calls this “learning poverty. Children cannot read and understand a short, age-appropriate text by age 10.” On the other hand, 60.2% of MYRP Grade 3 students in Somali-supported schools have developed the ability to read short texts. There is a vast magnitude between the per child cost study by the World Bank and MYRP, implying that the MYRP cost per child is efficient. Thus, these achievements should not be reversed, and regional and federal governments should maintain the progress contributed by the MYRP and advocate further funding to enable the educational continuation of crisis-affected children residing in the region’s displacement camps.