This article was written by Dr Ritesh Shah, Senior Lecturer in Comparative and International Education, Faculty of Education and Social Work, Waipapa Taumata Rau University of Auckland. It was originally published on New Zealand’s Newsroom on 28 June 2022, and on the ACCESS page on 31 June 2022.

More than 40 percent of the world’s refugees are children and young people under 18 and without education their future is bleak. Ritesh Shah explains why we need to move past ‘West is best’ in serving them.

The number of people displaced from their homes due to conflict, climate change, and/or natural disasters reached a new record of 89.3 million by the end of 2021.

To put this in perspective, this would be equivalent to the entire population of Germany or Turkey needing to move en masse. This figure does not even account for the more than 13 million displaced by the conflict in Ukraine since February 2022.

Children and youth under the age of 18 make up a sizeable proportion of the total displaced population (36.5 million, or 41 percent), and in the midst of displacement, education is often an important source of protection, sanctuary, hope and healing for these young people.

Schools and other educational institutions are often a first port of call in identifying children at risk of abuse, sexual and gender-related violence, psychosocial distress and/or forced recruitment into armed groups.

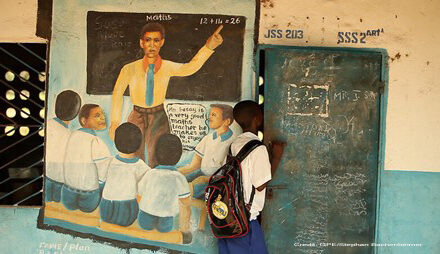

They are a place where children can safely socialise and engage with their peers and learn to be future citizens of their local, national and global communities. They are spaces where children regain their confidence, sense of hope for the future, and agency to change and overcome the circumstances they find themselves in. They can also provide the skills, knowledge and dispositions these young people need to achieve their aspirations and dreams.

But too often the potential for education to serve this healing function is unrealised. Often this is due to a range of economic, social, political factors which create significant barriers for families to enrol their children in their new communities and homes.

Those who do manage to access education often face significant challenges in remaining in the system. They can face social exclusion due to differences in language, culture, and religion, encounter poorly resourced and staffed learning spaces, face violence or discrimination, and/or find the hidden costs of schooling such as school uniforms, textbooks, learning resources or examination fees prohibitive.

Unfortunately, communities and countries which host the highest proportion of displaced learners are often ones struggling to meet the educational needs of their own populations. To expect them to address the specific needs and interests of displaced learners presents a double burden often too great to bear.

The result is that nearly half of refugee children remain out of school. For this reason, there is both a need and demand for diverse learning pathways for displaced learners and other marginalised populations globally, if education is to actually serve its potential.

This year, the United Nations Secretary General has challenged the global community to think about how to transform education itself, recognising its potential in helping us to resolve many of the global and local challenges we face. This requires action which doesn’t just tinker around the edges but radically rethinks the form, function and shape of learning provision, particularly for situations, such as learners in crisis and conflict, where schooling opportunities often fail to serve their function.

For the past year, I have been leading a research project called ACCESS, exploring what it would take to achieve the type of change necessary for out of school children and youth (OOSCY) to have educational opportunities that are available, accessible, adaptable and acceptable to them. It was found that often, the actions of donors, civil society, government to strengthen education provision for OOSCY maintains the status quo. While this work is necessary, it is insufficient to achieve the types of far-reaching, bold or disruptive change which the UN Secretary General notes is required.

For instance, a lot of effort has been put into producing evidence on “what works” to support learning for these children and youth, but without seeking to change the types of institutional and organisational cultures that preclude evidence from shaping future action.

This we found extends beyond shifting political will within the countries to the political and organisational will of donors, UN agencies and international NGOs supporting such efforts. The needs of young people are rarely at the forefront of their decision-making.

Instead, many actions are shape by organisational mandates and self-interest.

Sometimes the answers to these endemic issues lie within the system itself. Our research identified in most of the countries we worked in, very strong foundations off of which the international community could support existing efforts, including an inclusive national policy framework, innovative educational programmes led by civil society and refugee-led organisations, and/or extensive social support systems for the most marginalised.

Lastly and importantly, we found that there is a lot of presumption about what these young learners need or want. Many programmes and initiatives are set up without trying to understand what they desire from their education. It is no surprise then that they often fail to achieve their ambitions of providing a permanent, sustainable solution.

And this is where those of us living in countries in the ‘Global North’ come in. We need to stop asking what is in it for us, when our national budgets go towards international humanitarian and development assistance rather than domestic issues.

Concurrently, we need to remind our policy and decisionmakers that transformative change takes time, patience and fortitude. We need to encourage them to move beyond the view that the “West knows best” and to learn and build off the successes of governments in the developing world who have taken in and provided education to millions of those seeking refuge over the past decades.

We need to recognise that these investments in the futures of learners in crisis and conflict globally serves the betterment of our global community, and its long term peace, security, and sustainability.

Only then can education serve its healing and transformative purpose for the tens of millions of learners it is currently excluding.