This blog was written by Dr Margaret Ebubedike and Dr Saraswati Dawadi, Open University, UK.

ILO (2017), indicates that 40.3 million people globally are affected by the crime of human trafficking, including 24.9 million involved in forced labour and 15.4 in forced marriage. Women and girls account for 71% of the victims and 25% of the victims are children. Efforts of international governmental organisations and national governments to address human trafficking have focused on prevention with a quest to understand the experiences of survivors and how to successfully reintegrate them into society (Winterdyk, Perrin, & Reichel, 2011). Our initial scoping meetings with key stakeholders in the field indicate that the focus of support for survivors of human trafficking, often involves top-down dissemination of targeted content (Ebubedike & Dawadi, forthcoming). Methodologically, there is a move towards participatory approaches that focus on research done ‘for’ and ‘with’ survivors.

But what can we learn about how participatory approaches can foster deeper engagement with local contexts to create collaborative and innovative bottom-up approaches to knowledge co-creation and exchange? And how this can support the successful reintegration of trafficking survivors and reduce the likelihood of re-trafficking?

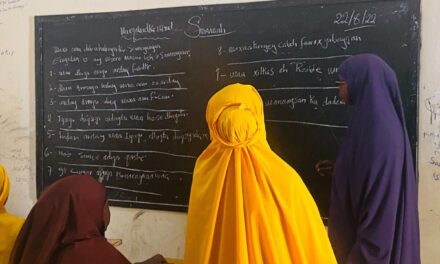

Our Stakeholder and Knowledge Exchange Engagement project (SKEEP), is funded by the Open University RES-Research-Enterprise impact acceleration fund. The project is in partnership with Women Trafficking and Child Labour Eradication Foundation (WOTCLEF), Nigeria; Peace Rehabilitation Centre (PRC), Nepal; and ACE Charity Africa. The project brought together a broad stakeholder cohort (government agencies, civil society groups, policy makers, and the girls themselves). It was framed around good practices and strategies used by NGO shelters in Nigeria and Nepal for rehabilitation and successful reintegration of female trafficking survivors and how these practices help reduce the incidence of re-trafficking. The event, attended by nearly one hundred participants from the two target countries, provided the participants with a very good platform to learn from each other.

Good practices in Nepal are mainly linked with the efforts of PRC to rehabilitate and reintegrate trafficking survivors back into society. For instance, the survivors receive vocational training and are provided with financial support to help them set-up businesses. However, this sort of aftercare economic empowerment initiative has not been mainstreamed in Nepal. During the events, it was strongly highlighted that inclusion of such initiatives has been effective for the successful reintegration of the victims into their community.

Additionally, PCR is working closely with communities to raise public awareness about human trafficking. Since there is a social stigma attached to victims of sex trafficking in Nepal, girls and women survivors of sex trafficking are not easily accepted in their society. Therefore, PCR is running different programmes at community level to change the mindset of people.

The Nigerian team highlighted good practices which include employing the support of known mentors to provide psychosocial support for the survivors. These known mentors are survivors themselves who have successfully reintegrated back into society and are now excelling in their various fields of endeavour. Another identified good practice was the use of survivors to create awareness about human trafficking. Participants jointly agreed that including voices of female survivors whose experiences are at the heart of the issue would foster inclusive ways of understanding how female survivors can be better supported. We argue that for practices that support female trafficking survivors to be made better, the voices of those with experiences of human trafficking, must be central to the conversations about them. The rationale being that an equitable response to victim support must recognise the need to include the voices and lived experiences of those with first-hand experience of human trafficking – recognising that each individual experience is unique and that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to a survivor’s support and rehabilitation.

A post-event survey revealed that SKEEP is enhancing participants’ understandings of trafficking issues in different contexts. Some participants describe how they are beginning to draw on newly formed partnerships to enhance their practice – these partnerships are already supporting and influencing their work and practice.

The event has offered the opportunity to think deeply about the importance of international collaboration in responding to the issues of girls’ trafficking – (Participant from Nepal).

I am now able to collaborate with and leverage on the expertise of other stakeholders to provide better support for survivors living in our shelter– (Participant from Nigeria).

These insights offer a new understanding about the need to foster a community of practice (CoP) among the NGO shelters, key stakeholders, and the girls themselves – which will be built on trust, open lines of communication, and co-development. Learning from SKEEP reveals that creating a space for co-creation of knowledge among key actors of human trafficking will foster equitable and sustainable practices for supporting female trafficking survivors.