This article is written by Dr Janet Baah, who holds a PhD in International Education and Development. She is a Town Councillor and previous Mayor of Lewes, East Sussex, UK, a Governor and Steering Committee member of the Sussex NHS Foundation Trust, Board member of the Southdown’s Partnership Trust, and Trainer/Mentor of the African Liberal Network Women’s Empowerment Project.

Over the last two decades, non-state actors have been actively involved in education provision for disadvantaged children in low-income countries. We also know too well that the non-state markets have their ups and downs, so the main findings from the 2021/22 Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report are perhaps nothing out of the ordinary. However, the report is interesting for two reasons:

- First, it calls on policymakers to have a granular analysis of who chooses and who loses out on non-state access. Thus, a differentiated understanding of contextual conditions/issues and a careful analysis of non-state actors’ role in meeting SDG 4. While relatively well-off households have benefited from non-state education, most disadvantaged households living in low-income countries have not. Nevertheless, given the fact that ‘markets’ are now encouraged to fill the access gaps left by governments, my guess is that this trend will soon be the norm.

- Second, inadequate data and evidence make it too easy to focus on what we can safely measure in terms of children’s rights to education and forget just how complex meeting these rights are.

The GEM Report asked whether all learners receive the quality of education they are entitled to. This question depends on what we are measuring (Srivastava, 2013), what quality looks like, and whether all learners have access to this measure of quality. The current evidence only focuses on effectiveness, input, and whether non-state schools are registered or not. This appears simplistic, given that the purpose of education goes beyond these indicators (Biesta, 2009). More often we tend to act quickly on what we think might affect the league table, at the expense of education’s intrinsic purpose. When comparing government and private schools, especially in low- and middle-income countries, the GEM Report argues that “parents who can choose schools do so because of religious beliefs, convenience and student demographic characteristics rather than quality, about which they rarely have sufficient information”. My work (forthcoming) includes quality variables that are normally unobserved into the education quality debate.

My mixed-method study provides new evidence on who accesses government or ‘low-fee’ private schools in inner-city Accra, Ghana, based on individual and household characteristics. The study also investigates the differential experiences and aspirations based on the type of school students attended and their household background characteristics. Some key lessons learned:

- In the inner-city environment, over-aged children, children from larger families, and basic asset ownership increases a child’s chances of accessing a government school. However, the uneven or inadequate government places means some households within these categories have to pay for a place in the low-fee sector until a government place becomes available. They have no choice compared to the relatively wealthier households who primarily see low-fee private access as a better option for success and educational progress for their children. This points to diversity of “quality” within the low-fee private school (LFPS) sector in the inner-city context.

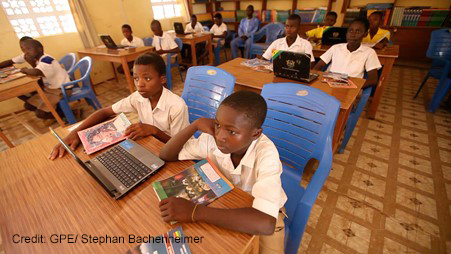

- Government school children report they have better teaching/learning experiences and are more satisfied with the overall schooling experiences than their privately-schooled peers. Perhaps this is because government schoolteachers are all qualified teachers. However, the policy environment in private schools supports and encourages strict supervision, forcing teachers to stay on task, resulting in positive classroom management. Over-aged children and boys have substantially negative schooling experiences irrespective of the type of school they attend. Both government and private school environments were found to be uninspiring, violent, and uncomfortable mainly because of the widespread and daily use of corporal punishment in schools.

- Government and private school children believe that schooling is a necessary and useful route to achieving their career aspirations. However, private school children significantly and substantially aspire to professional careers requiring further education.

Some useful implications and recommendations

The findings suggest that the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education (FCUBE) has been poorly implemented, given that many vulnerable and marginalised households are still depending on and accessing private schools of lower quality, not by choice but by necessity. Governments are encouraged to make the improvements necessary to support access to education among disadvantaged households. This includes building schools in deprived communities to offer truly free places at various levels of education.

While the non-state sector is currently contributing to SDG4 by bridging the access gap, it is not a solution to meeting the rights of vulnerable children in the longer term. The private sector is now profiting out of the lack of government places. This is wrong, especially when the teaching/learning and the overall satisfaction are of lower quality. Therefore, the GEM Report calls on governments to “to see all institutions, students and teachers as part of a single system” that fulfils the right to education for all.

The GEM Report urges governments to establish “quality standards, covering not just inputs but also results, and protect those who have the most to lose”. Data on this is patchy, therefore, Ministries of Education should be collecting, reporting, and tracking how the non-state sector is performing, including children’s schooling experiences through to higher education. If a pattern emerges in data suggesting, for instance, that certain groups of children, including those who have less aptitude for academic subjects are disproportionately not having positive schooling experiences and are therefore ‘short-changed’, then the government should be required through policies to implement support programmes to address those inequalities.