This blog was written by Susan Nicolai, Senior Research Fellow, and Moizza Binat Sarwar, Research Fellow at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI). It was originally published on the ODI website on 22 June 2021.

Leaders at this year’s G20 Education Ministerial meeting and upcoming Global Education Summit are looking at the future of education systems, taking into account experience gained during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The compounded challenge is of course that there has long been a learning crisis, with more than half – an estimated 617 million – of children and adolescents globally unable to reach minimum proficiency levels in reading and mathematics, even though two thirds of them are in school. How to best address this failure is subject to rich debate amongst education sector leaders, with call and consensus centering on foundational literacy and numeracy, alongside accountability. Here at ODI, we recently held a panel discussion: ‘Pathways toward an education that leaves no one behind’, where what is needed to push the agenda forward was further considered along with a group of experts from ADEA, ASER and UNICEF Innocenti.

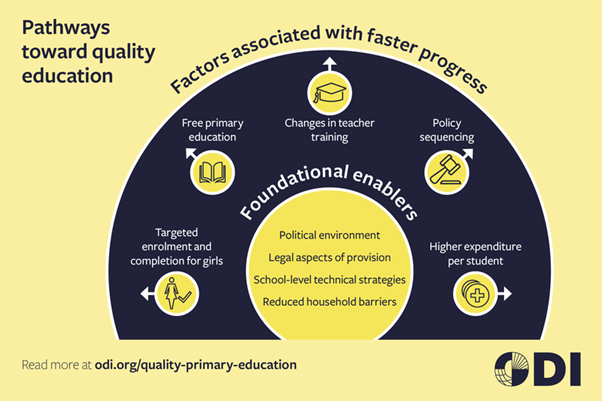

We drew on our recent paper looking back at experience of previously successful education strategies where we reviewed policies and plans in 38 countries that have made faster progress in primary completion rates (PCR) – and, where discernible, learning outcomes – between 2000 and 2017. This revealed a set of foundational enablers in primary education completion could be identified across four areas: the political environment, legal aspects of provision, school-level technical strategies and reduction of household barriers. Overall, countries with low PCR in 2000 made the greatest progress possibly because they were oriented towards increasing coverage and reaching excluded groups. In contrast, in countries with already high or moderate PCR, it was more difficult to reach those still excluded.

To further interrogate the significance of these factors, we used multivariate analyses and ran a series of robustness tests to find that:

- Focus on girls matters. Faster progress was achieved by countries that put in place laws targeting enrolment and completion for girls, and in countries that collected data on education for girls, with scholarships for girls attending primary education particularly significant.

- Availability and access are key. Our regressions showed that making primary education free mattered more than making education compulsory.

- Teachers, teachers, teachers. Countries that introduced changes in teacher training (pre and in-service) made faster progress on improving learning outcomes.

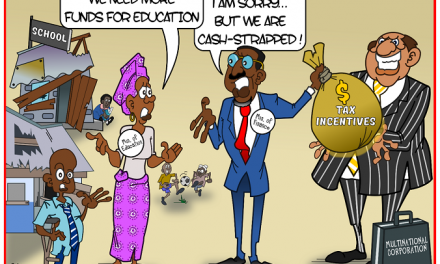

- Higher expenditure per student. Education gains – at least in terms of PCR – were found to be significantly better when expenditure per student is higher, when we extended analysis from our sample countries to a broader set of 137 countries.

- Policy sequencing adds value. Finally, the importance of policy sequencing emerged in our sample, showing that a trade-off between completion and learning is not inevitable. Countries such as Kyrgyzstan, Lesotho, Guatemala, Ghana, Rwanda, Albania, Ecuador, Poland, Morocco and Oman initiated clusters of strategies that positively impacted both completion rates and learning outcomes in primary education.

Interestingly, in our analysis, infrastructure expansion was negatively associated with improvements in learning outcomes, indicating that countries heavily focused on expanding the education system overlook issues of education quality or perhaps sacrifice quality for coverage. In addition, while we were further able to see an association with increased foreign aid and debt relief, this did not necessarily seem to be a determinant factor in education progress.

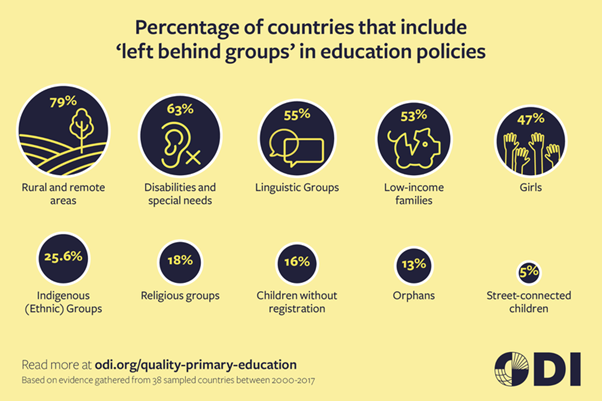

When we further looked at which groups of children are being left behind from the rise in PCR, we found that, in practice, governments operate along a hierarchy of priority. A higher level of education policy attention is generally given to children in rural and remote areas, disadvantaged linguistic groups, children with disabilities and special needs and girls. Much lower levels of policy attention were found in relation to indigenous and religious groups, children without registration, orphans and children connected to the street. Worryingly, government plans were largely silent on education for other groups, including children displaced by conflict, non-documented migrants, those living in informal settlements and enslaved children.

Increased visible policy attention is important to reaching marginalised groups of children too often excluded from education and learning across countries. Lessons learned in terms of how a greater focus on girls supports broader education progress show that policy efforts to ‘leave no one behind’ can make a difference for the system as a whole.

So what does looking back mean for ways forward? Our panel highlighted a need to be responsive to our changed world in trying new approaches, as evidence is clear that the majority of children and adolescents – let alone those who are most marginalised – often haven’t benefited from education reform strategies and approaches to date. Some of the areas emerging from the group that are critical in advancing education and learning, especially in light of Covid-19, were:

- Investing in children’s readiness to learn both through emphasis on early childhood education, but also throughout the early grades, given the protracted period older children have spent out of school.

- Supporting continuity of learning will necessarily require an emphasis on remedial education, supporting teachers to deliver catch-up education and adapting curriculum and pedagogy to teach children who have been out of school for over a year.

- Moving beyond a focus on purely academic skills to broaden the definition of foundational skills to include social and emotional learning, particularly for children with complex needs

- Waive registration requirements and examination fees for children and ensure that children without registration documents, displaced children and migrant children have access to schools wherever they are.

- Ensure countries are set up to be connected for distance education through no, low and high EdTech options as appropriate to promote resilience of education systems in future crises and to enable remedial learning at home.

There is a clearly a complex set of choices in front of governments as they turn to education recovery and renewal. Building on past experience alongside attention to what is needed in our changing world is a critical part of the puzzle.