This blog was written by Lee Crawfurd, Senior Research Associate; Susannah Hares, Co-Director of Education Policy and Senior Policy Associate; Justin Sandefur, Senior Fellow; and Rachel Silverman, Policy Fellow from the Center for Global Development (CGDev). This was originally published on the Center for Global Development blog site on the 23 April 2020.

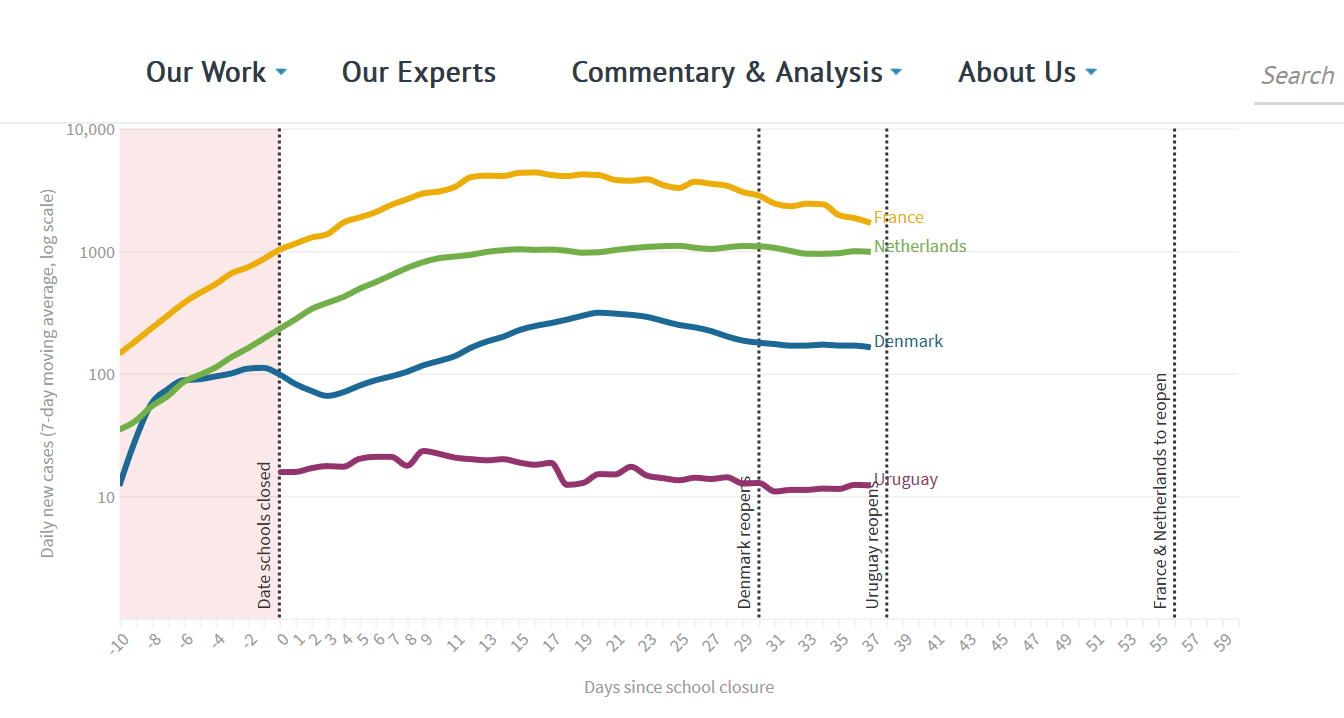

Thirty days after closing its schools, Denmark reopened them last week. France and the Netherlands plan to follow suit in early May. Many developing countries were much quicker in closing schools—13 African countries closed schools nationally before the first COVID-19 case was reported. Even as Ghana lifts its lockdown in major metropolitan areas, it has opted to keep schools closed, and a leaked plan to reopen schools in South Africa is expected to meet stiff resistance from teachers unions.

Thirty days after closing its schools, Denmark reopened them last week. France and the Netherlands plan to follow suit in early May. Many developing countries were much quicker in closing schools—13 African countries closed schools nationally before the first COVID-19 case was reported. Even as Ghana lifts its lockdown in major metropolitan areas, it has opted to keep schools closed, and a leaked plan to reopen schools in South Africa is expected to meet stiff resistance from teachers unions.

On what basis have some European policymakers decided that it’s wise to reopen schools? And how will those calculations differ in low- and middle-income countries?

| See the interactive tracker graph on the original blog post:

Past the peak? Daily COVID cases in European countries reopening schools. |

School closures force policymakers to weigh possible reductions in disease transmission against the adverse social and economic effects. Our colleagues have noted that much of the modelling to support COVID-19 policy decisions uses assumptions that may not translate readily to developing country contexts. The same applies for school closures. In other words, a “one-size-fits-all” approach to school reopening may not be the right one.

Tentative evidence suggests children are not a primary vector for COVID transmission

The main consideration for any government in deciding whether or not to open schools is not about education or economics, but virology and epidemiology. We are not virologists or epidemiologists, and offer no new insights here. But the existing epidemiological literature does offer a few relevant findings for policymakers confronting hard choices about reopening schools.

First, children are less vulnerable to serious coronavirus illness and death than adults. In the United States, for example, the CDC reports that 21,050 Americans had died of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 by April 18, but just 3 fatalities were in children 14 and under (media outlets report many more cases).

Second, and much more provisionally, emerging evidence also suggests children play a smaller role in transmission. A study of household clusters in China found that children (< age 20) were only about a third to a quarter as susceptible to infection as adults and also slightly less infectious to others. Studies across Asia find that children are rarely the index case for household clusters, implying a relatively limited role of school-based transmission. In Iceland and Japan, children under 10 who were targeted for testing following exposure were substantially less likely to test positive than similarly high-risk but older individuals; in one small Italian town, near universal (86 percent) testing showed that zero children under 10 had been infected, compared to 2.6 percent of the general population. It might be possible to reopen schools while maintaining social distancing in communities and workplaces and therefore managing transmission.

When researchers from University College London recently published a rapid systematic review on school closures in The Lancet Global Health, one number jumped out and was widely cited as a reason to accelerate school reopening: school closures were expected to reduce COVID-19 deaths by “just” 2-5 percent, a relatively modest (though still meaningful) effect given the high costs of keeping kids out of school and compared to other forms of social distancing.

However, the evidence on child infection and transmission is still far from conclusive, and the relatively high prevalence of asymptomatic infections in children (among lab-confirmed coronavirus cases) may make case detection and control more difficult.

School closures will exacerbate existing inequalities in developing countries

Many of the costs of closing schools are common to rich and poor countries—and some, like the impact on labor supply—may even be less severe in the developing world. But those costs are born by children and households that are much poorer at baseline.

The learning loss as a result of the pandemic may be significant. Relatively few low-income countries have launched distance learning programs and—of those that have—most will be delivered via radio. These may play an important role in keeping children connected to their education and mean fewer children drop out of school. But the impact on learning is likely to be substantial—a study from Malawi suggested that literacy loss during the long (seven week) school holiday was almost as big as the gains that a USAID-funded literacy program generated during the school year.

School meals represent a lifeline for some children, keeping them from hunger and malnutrition. With schools closed, that lifeline is disappearing—creating a window for greater short-term, acute malnutrition (and vulnerability to infection) plus potential long-term effects on vulnerable children’s health and cognition. The World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that about 369 million children around the world are missing out on school meals because of COVID-19 school closures. Most European countries, and some low- and middle-income countries (and the WFP itself), are offering alternative mechanisms to keep school children fed during the crisis—but in most countries, it’s unlikely that these will be rolled out at sufficient scale to replace the enormous reach of regular school feeding. By reopening the schools, we can restore this vital service and improve children’s nutritional status.

Children may be more at risk of violence or other abuse while schools are closed. We have not yet found reliable data on violence against children during the lockdown, but reports suggest higher rates of domestic abuse. Half of Pakistanis surveyed by Ipsos think that parents beat their children more during lockdown. The United Nations Development Program estimated that teenage pregnancies in some communities in Sierra Leone rose by 65 percent as a result of school closures, and incidents of sexual assault of children increased. Reopening schools faster may mitigate some of these adverse effects on adolescent girls observed during the Ebola school closures.

Children staying home from school has implications for their parents’ productivity. A rapid survey by BRAC in Bangladesh across a large sample of the poor suggests that income has fallen by more than 70 percent since the onset of the epidemic. These income losses stem from the broader lockdown, rather than school closures specifically. Indeed, childcare responsibilities may be a less important constraint to parental labor supply in low-income countries—with a large share of the workforce in subsistence agriculture and the informal sector—than in advanced economies.

If passing the peak for new infections is the first hurdle for opening schools, many developing countries aren’t there yet

On average, confirmed COVID cases are significantly lower in low-income compared to high-income countries to date—but the epidemic in India, Bangladesh, and many African countries is still in its early days compared to many industrialized countries.

| See the interactive tracker graph on the original blog post:

Still Climbing: Daily COVID cases since school closed in selected developing countries |

India has the highest (confirmed) burden among lower-middle income countries with over 16,000 cases and 681 deaths at time of writing—compared to well over 100,000 cases in France and Germany, both of which have populations that are an order of magnitude smaller. In Africa, only Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, and South Africa have more than 2,000 cases; more than 20 countries have less than 50 confirmed cases. Caution is in order: it’s not immediately clear whether these numbers reflect genuinely low incidence, limited testing capacity, or some combination of the two—and the answer probably varies country by country. Daily confirmed case counts are still growing across most developing countries, and India and Bangladesh may be on exponential growth paths similar to those seen in Europe. But at least as of yet, and with some exceptions, most low- and middle-income countries are not seeing the overwhelming rates of serious illness and death experienced elsewhere.

Even when cases fall, the school reopening calculation may look different in developing countries for a variety of reasons.

Developing countries may struggle to implement the reopening protocols proposed in Europe

Upon reopening, the Danish government instructed schools to keep two metres between teacher and students and, where possible, between students. Children cannot mix outside of their teaching group to avoid inter-class contact and are not permitted to share food or bring toys from home to school.

Implementing measures like this will be challenging, even in well-resourced school systems. Teachers have raised concerns about the viability of the guidelines and the risks that reopening schools pose to their health.

Keeping kids two meters apart may be impossible. Plans for school reopening in Europe stress school-based mitigation and social distancing, phased reopening for different year groups, frequent handwashing, staggered arrivals, and so on. Even in Europe, many are expressing skepticism about the ability of teachers to sustain these social distancing measures, particularly between children. It’s unclear (and unlikely) that these measures would be viable across most schools in low- and middle-income countries. European primary schools have an average of one teacher per 13 students; meanwhile, in low-income countries each teacher is responsible for 40 children. Physically, it may not be possible to keep children 2 metres apart in small, crowded classrooms; even if it were, teachers would face challenges managing the interactions of 40 six-year-olds.

Frequent hand washing may also pose a problem. As of 2016, less than a quarter of schools in sub-Saharan Africa, and less than half of schools in Indonesia, Cambodia, and the Philippines, offered “basic” hygiene services—defined modestly as a handwashing facility with soap and water.

Developing countries may be more vulnerable to school-based outbreaks of COVID-19. There are some reasons to think developing countries may be more vulnerable to school-based outbreaks of COVID-19 than their European counterparts. Testing capacity is highly constrained in most developing countries, meaning a school-based cluster of infections would probably become quite large and spread more broadly before it could be identified and contained.

Further, even as European countries consider a gradual reopening of schools and other social infrastructure, many are suggesting (or even requiring) sustained “cocooning” for the elderly, immunocompromised, and other groups at elevated risk from coronavirus. In sub-Saharan Africa, where multigenerational homes are common and many children live with elderly relatives—in part a legacy of the AIDS crisis—it will be far more difficult to isolate potentially infected children from more vulnerable family members. And in societies where malnutrition, unmanaged chronic disease, tuberculosis, indoor air pollution, and unsuppressed HIV are more common, children and working-age adults may also experience heightened vulnerability to the disease in ways we don’t yet understand. If individuals do become seriously ill, limited hospital capacity and ventilator availability may limit access to care and drive up mortality.

In short, the health impact of school-based transmission will look different in developing countries than in Europe, and policymakers may consider it premature or reckless to dial up transmission risk.

For now, keeping schools closed appears to be good politics. In most countries teacher unions have supported school closures and may understandably feel that their members are being asked to return to work prematurely and put their health at risk, even in countries where infection rates are low. Without the support of the education workforce, it will be extremely challenging to manage the already complex reopening process effectively and safely. Public opinion may also be in support of schools remaining closed. A survey in March of 10,000 Indian parents found that just 9 percent wanted schools to reopen within the next two months.

No country will have taken the decision to close schools lightly, and the decision to reopen will be just as difficult. There are still a great many unknowns—notably how infectious children can be to each other and to adults, and how viable distancing protocols are in schools. Let’s hope we learn quickly.

Thanks to Ana Minardi for excellent research assistance and to Kira Boe for her helpful contributions.