This blog was written by Mark Chapple for the Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE). It summarises the key points from a new report by the Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Action. This blog was originally published on the INEE website on 16 July 2020.

School closure means less learning and increased protection risks, especially for children and youth in crisis contexts

Imagine you’re a child, your school has closed, you’re stuck at home, you can’t see your friends, you can’t learn, you’re scared and worried about your future.

Now imagine that school is the place where you receive your main meal of the day, the place where you get support in dealing with traumas you’ve experienced, the place you feel safe.

Now imagine that school is the place where you receive your main meal of the day, the place where you get support in dealing with traumas you’ve experienced, the place you feel safe.

It’s no longer open for you.

This is the reality for many children and young people around the world now. Governments trying to stop the spread of the COVID-19 global pandemic have ordered an unprecedented level of school closures, which at their height affected up to 90% of all learners globally. Whilst in some cases these closures may have been necessary, the decision did not always take into account the impact on the wider wellbeing of children and young people.

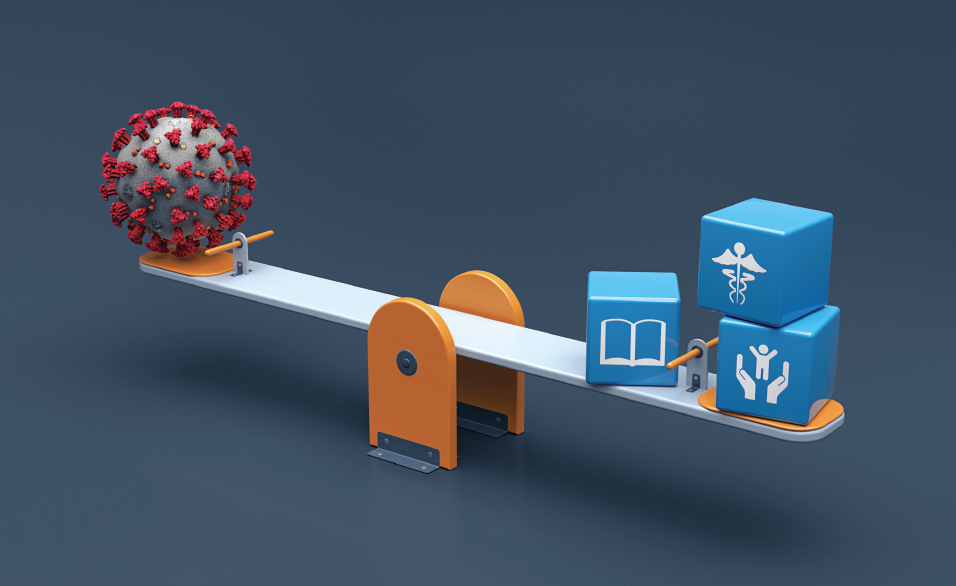

We know that education is one of the main drivers against inequality, a way to foster peace, to catalyse regeneration, and to bring hope to the futures of many vulnerable children and young people around the world. Education can also provide a protective environment, psychosocial support, socialisation, school feeding, and referrals into other specialised child-protection and health services – all factors that are key to healthy and holistic development.

Many children and young people are suffering greatly from school closures, missing out on education and being exposed to other child protection risks such as child labour, early marriage, separation from family, and other forms of abuse, neglect, exploitation and violence.

The most vulnerable in society are likely to be the worst affected. If you were a refugee child before the pandemic you were more than twice as likely than a non-refugee to be out of school. COVID-19 is only making this worse. Many of those now affected by school closures in poorer countries and crisis-contexts may never go back to school. UNHCR & Malala Fund estimate that half of all refugee girls will not return when classrooms reopen. Recent research from Christian Aid also notes that: “Experience from the west African Ebola epidemic shows school closures led to higher rates of permanent dropout for girls, and to a rise in child labour, neglect, sexual abuse, teenage pregnancies and early marriage.” The life chances of a whole generation are at risk of being devastated

Preventing transmission of COVID-19 is necessary to contain it, but in some high density environments- refugee camps, informal settlements, low resource neighbourhoods – social distancing may not be practical and closing schools may leave children at equal or greater risk of infection.

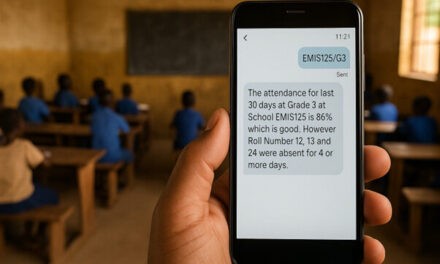

The analysis of all the risks and impacts across health, education, and child protection needs to be contextually specific, down to school-area, undertaken swiftly and updated regularly to ensure children and young people are not further disadvantaged by COVID-19.

Click to download the new policy paper by INEE and The Alliance.