This article is written by Vijay Siddharth Pillai, a recent graduate in Education and International Development from the University of Cambridge and a former Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellow (India). He currently works as an Education Consultant (Education in Emergencies) at the Ministry of Education in Afghanistan. This blog is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development.

Amidst school closures, governments across the world are trying to ensure continuity of learning through various means, including instructional videos and online tools like Google Classroom. However, its effectiveness depends on proximal factors like its accessibility and consistent use. Analysis of the extent and profile of traffic to educational YouTube channels and Google Classroom shows that the barriers are stacked up against children of less developed and fragile nations when it comes to accessing these online tools and platforms.

Instructional videos and educational YouTube channels of Ministries of Education

Developing countries with poor internet penetration have mostly depended on television channels for broadcasting instructional videos. However, as a response to COVID-19, less developed and fragile countries have also been using educational YouTube channels. Details about these YouTube channels are mentioned in the briefs of UNESCO and World Bank which summarise the response of different states to school closures. On these YouTube channels, the instructional videos are being uploaded so that they are available on demand for various kinds of learners. For instance, the Ministry of Education in Afghanistan states on its website that the channel shall provide access to learners who are “deprived of TV lessons” or “lag behind” in watching the videos on television.

As regular and punctual viewing of TV lessons could not be ensured due to various reasons (like household chores, frequent power cuts), the YouTube channel may be the only resource for children to tackle such barriers. The fact that a typical Pakistani household faces 16 hours a day of scheduled blackouts in the summer season (IFC 2015) gives us an idea of the significance of such barriers. Such barriers are more relevant for learners of higher grades where each instructional video may be closely connected with the previous instructional video, which they may not have watched on TV or failed to understand it well when it was broadcasted. Hence, the extent and profile of viewership of the YouTube channels show how these channels fair as a primary and/or secondary source of learning at home.

Viewership profile for Albania, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Pakistan (Punjab), Palestine, Rwanda and Yemen

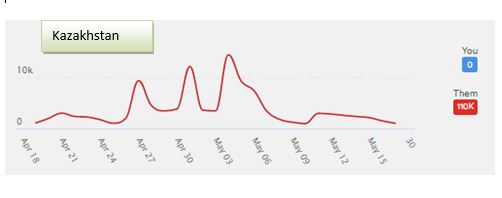

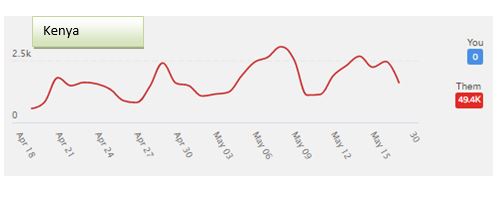

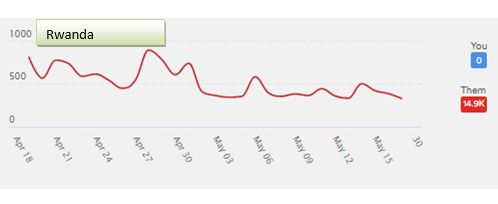

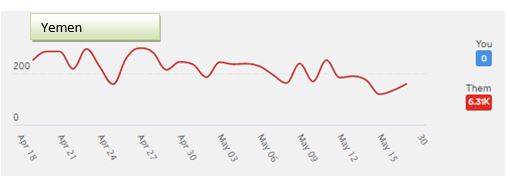

The viewership profile of the educational YouTube channels of various countries for the past 30 days was obtained using TubeBuddy, which is a browser extension that adds an additional layer of tools on top of YouTube. Viewership profile (as on 17th May, 2020) from Albania, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Pakistan (Punjab), Palestine, Rwanda and Yemen are shown below in Figure 1. The number highlighted in red in the figure (for instance, 57.9K for Albania) refers to the total number of views for all the videos in the YouTube channel in the past 30 days. [The figure in blue (which is zero in all graphs) is of no consequence here as it refers to the views secured by the author’s channel.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 1: Analysis of the educational YouTube channels of Albania, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Pakistan, Palestine, Rwanda and Yemen (Source: TubeBuddy)

As shown in the graphs of Figure 1, all the above mentioned countries have 200-2,000 views (all videos in the channel combined) on the day the data was collected (17th May, 2020). Moreover, the irregular nature of the curve (except Kenya, which shows some kind of regularity) shows that it is highly unlikely that it is consistently used as a primary source of learning at home.

Viewership profile for Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Croatia

However developing countries which have their YouTube channels linked to mature learning management systems or virtual classrooms systems have better profiles of viewership. Viewership profile for YouTube channels of Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Croatia are shown below in Figure 2:

Figure 2: Analysis of the educational YouTube channels of Azerbaijan, Ukraine and Croatia (Source: TubeBuddy)

The graphs above in Figure 2 show that the daily views of the videos in educational YouTube channels of these countries range from 50,000 to 500,000. Additionally, one can see consistency in the viewing profile with views dropping on weekends. Such viewership profiles have arguably become possible because learners are continuously engaged and held accountable through other online tools. According to the World Bank, Croatia has virtual classrooms where teachers communicate daily with students, monitor their performance and completion of tasks. Similarly, Azerbaijan also has a virtual school project where each student has a personal account.Upon entering the virtual school system, students are able to enter age-appropriate classes, watch embedded lessons from YouTube, and engage in audio-visual communication with students and teachers and complete the weekly, teacher-prepared assignments on those topics. Unlike Azerbaijan, the All-Ukrainian Online School project at a national level doesn’t track the work of learners at home. The Ministry has delegated the responsibility for learner engagement to school principals and teachers. The Ministry in its guidelines highlights that “In the conditions of distance learning, when teachers and students cannot be close, the interaction between all participants of the educational process…becomes especially important”. While the Ministry provides pedagogical freedom to schools to use online tools which suit the teachers, students and caregivers, many school teachers have been working with the Google Classroom platform for the past three years where they test, monitor and provide useful videos and presentation. Reports from Ukraine suggest that video lectures from their YouTube channel are being used in the virtual sessions conducted by teachers.

Digital Divide impacting learner engagement during remote learning – the case of Google Classroom

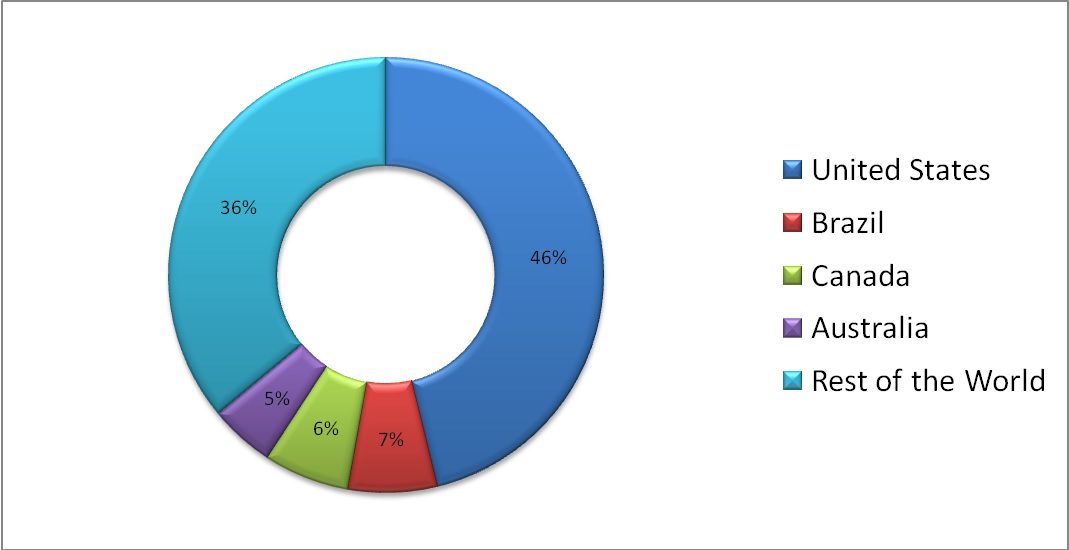

Countries which are able to ensure some sort of learner engagement through learning management systems or online tools, such as Google Classroom and Microsoft Teams, are in a better position to ensure greater participation and consistency in remote learning, as seen through the viewership profiles of their YouTube channels. However, the access and use of these online tools which ensure sustained learner engagement is severely skewed in favour of a few states. An estimation of the access and use of Google Classroom by different countries was done with data from ahrefs.com.[i] It was found that 64% of the global monthly search traffic to Google Classroom for the past 30 days (April 22 to May 21) comes from four countries, namely US, Brazil, Canada and Australia. As per UNESCO data (2018), these countries account for less than 10% of the total population of compulsory school age. The share of these countries in the global search traffic is shown below in Figure 3:

Figure 3: Estimated distribution of the global monthly search traffic to Google Classroom for the past 30 days (April 22 to May 21) (Source: ahrefs.com)

As observed by Lyudmyla Yurchenko, a biology teacher in Ukraine, schoolchildren may not feel responsible when it comes to remote learning. Countries, especially those with a large proportion of illiterate and semi-literate parents, need to recognise and act upon this fact. Instructional videos will gain higher and consistent viewership when they are part of the broader learner engagement strategy. One cannot expect students suddenly to become responsible and diligent self-learners. They need to be monitored and motivated through constant human engagement through high-tech (e.g. virtual sessions), low-tech (e.g. phone calls) or no-tech options (e.g. home visits). Amidst lockdown, resource deprived, digitally disconnected nations are failing to ensure such engagement. Such engagement cannot be ensured by solely depending on instructional videos, however engaging and intuitive they might be. As Walter Lippmann said, “You cannot endow even the best machine with initiative; the jolliest steam-roller will not plant flowers.”

[i]ahrefs.com estimates the total monthly search traffic to the website “from the top 100 organic search results. It is calculated as the sum of traffic from all organic keywords for which the target ranks.” Even though ahrefs.com cannot precisely show how much organic traffic a site gets, it works “incredibly well for comparing traffic to sites in the same niche”. https://ahrefs.com/blog/seo-metrics/#section7

It offers the freedom to join or leave the class as per the choice. Those people who are working can find this feature convenient. Since they are not required to be present in the online class compulsorily, they can continue their education with their work.