This blog was written by Cyril Brandt, a postdoctoral student, and Tom de Herdt, professor of development and Chair of the Institute of Development Policy, University of Antwerp. They have recently published an article together – reference and highlights of the research are detailed here.

It is well-known that teachers in many low income, conflict-affected contexts are poorly paid. The circumstances under which they receive their salaries are less known.

In our recently published article, we investigate a recent reform of teacher payments in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) that intended to modernise teacher payments. It sought to replace human intermediaries in salary distribution with individual bank accounts. The reform had four objectives:

- enabling teachers to receive their full salaries without deductions,

- reducing possibilities for embezzlement,

- extending the banking infrastructure

- increasing the transparency of public expenditures.

The so-called bancarisation reform became a flagship reform of the technocratic Congolese government in the reform years of 2012-13. It was conceived and implemented without external assistance.

In our analysis we demonstrate two main aspects:

- A teacher payment reform can wreak havoc by increasing the distances teachers have to travel to collect salaries.

- A teacher payment reform can deepen the existing unevenness in the geography of statehood and public services.

In our mixed-methods study, we gathered qualitative data and made use of a unique quantitative dataset that allowed us to (a) estimate distances teachers need to travel to collect their salaries and (b) the spread of salary providers across the country.

Increased distances

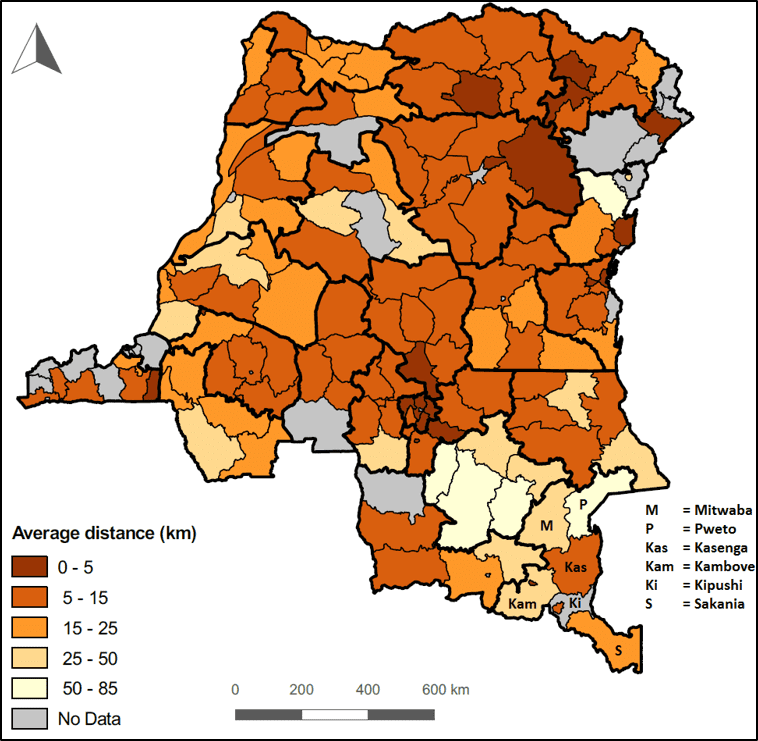

The map below represents the territories of the DR Congo. Darker colours represent higher distances between schools and payment points. It clearly reveals that teachers in many corners of the country need to travel significant distances to withdraw their money from banks or collect it from temporary payment points. Before the reform, collective payments were made and head teachers, or other intermediaries, collected and distributed salaries for many teachers at once.

However, the map hides a range of qualitative aspects:

- road conditions are often very poor,

- teachers walk or travel on bike,

- teachers need to spend money on food and accommodation,

- teachers might need to wait for several days before being served, and

- most strikingly, teachers might have to travel through conflict-affected areas.

A hybrid system of providers

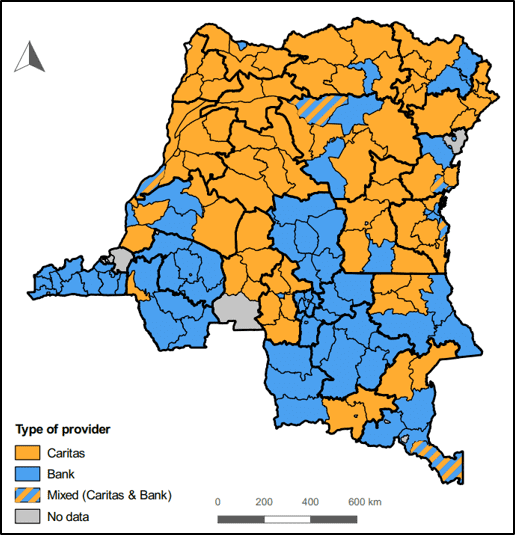

As well as creating these distances and challenges, the bancarisation reform in fact failed to establish bank payments to all teachers. The ambitious but poorly-planned attempt to replace one system of payments with another failed. Instead, different systems have been superimposed. Mobile phone companies have been sub-contracted by banks. However, mobile phone coverage in some parts of the country remain poor and several providers had to relinquish on their attempt to use the reform to grow their customer base.

The Catholic NGO Caritas is another key actor in the reform process: Caritas already paid teachers, before the reform but was then sidelined. Gradually, the government had no other choice but to turn back to Caritas and ask for its help. The following map uses data from May 2018 and demonstrates that a high number of territories are indeed not served by banks, but by Caritas

These data underline that the reform did not replace one mode of payments by another. Instead, there are now several different modes at play, further decreasing the transparency and governability of teacher payments. In sum, the reform deepened existing inequalities in the provision of public services while failing to comprehensively control the teaching workforce.

Reference:

Brandt, Cyril Owen, and Tom De Herdt. 2020. ‘Reshaping the Reach of the State: The Politics of a Teacher Payment Reform in the DR Congo’. Journal of Modern African Studies 58 (1): 23–43.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks