This blog was written by Anusha Ghosh, Senior Economist and Katarzyna Kubacka, Senior Specialist International Education and Development, at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER). It was originally published on the NFER blog website on 2 June 2020.

As of April 2020, nearly 1.6 billion children and young people worldwide have been affected by COVID-19-driven school closures, according to UNESCO estimates. Closures put at risk not only students’ learning, but also their future earnings and employment prospects[i] [ii]. Lockdowns can also pose heightened risk to learners’ physical and mental safety, especially for the most vulnerable, such as poor girls and learners with disability. For many of the world’s students, schools are not only the sole source of learning but also provide access to essential services such as health and food. As schools start to reopen in many countries, it is an apt moment to reflect on the impact of this crisis on educational inequalities and to consider how this difficult time can inform action to create more inclusive educational systems.

While online learning is a logical alternative to learning in schools, it is not an inclusive solution. Only 19% of the population in the poorest countries are internet users, with sub-Saharan Africa reporting the lowest proportions of users. There are also large gaps in access to computers across socio-economic groups, within countries. In particular, online learning often excludes children with disabilities or special education needs. This is due to the limited availability of accessible online learning materials, especially in remote areas. Many learners also lack specialised support needed to support their learning, particularly in low-income countries.

While online learning is a logical alternative to learning in schools, it is not an inclusive solution. Only 19% of the population in the poorest countries are internet users, with sub-Saharan Africa reporting the lowest proportions of users. There are also large gaps in access to computers across socio-economic groups, within countries. In particular, online learning often excludes children with disabilities or special education needs. This is due to the limited availability of accessible online learning materials, especially in remote areas. Many learners also lack specialised support needed to support their learning, particularly in low-income countries.

Sustained school closures may undermine the progress in girls’ education that has been made over the last decades. Girls in poorer countries have lower levels of access to the internet relative to boys, which means that they could lose out on learning at home. Moreover, inequalities in school completion rates may worsen as girls are less likely to return to school once schools reopen. Plan International highlights additional risks of lockdown, such as an increased risk of domestic violence, sexual and gender-based violence, reduced access to sexual and reproductive health services, and an increased burden of unpaid care and domestic work.

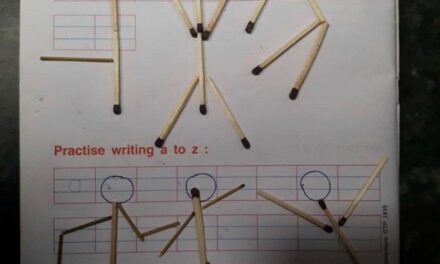

These potentially devastating consequences underscore the need to adapt current solutions to serve a wider range of needs. Many governments and sector leaders have acted with agility to respond to the current situation. Supplementing online learning with low-technology solutions may mitigate the problem of unequal internet access. Afghanistan has developed print-based, self-instructional materials as a part of its COVID-19 response. In Malawi and Rwanda, learning programmes are being delivered through radio to reach more students. Online platforms can also be made more inclusive. In Eastern Europe and Central Asia, UNFPA has developed an online sexuality education tool for learners with autism.

Lessons learned during this crisis highlight the need for policy action to correct system-level inequities that school closures have brought into focus. In supporting the process of redesign towards more inclusive education systems, there are some key considerations and action points that emerge:

- Prioritising the most vulnerable students. Where phased re-openings are possible, the vulnerable should be prioritised and barriers to entry minimised, through abandoning fees and offering financial support, taking into consideration local contexts and learning needs. Expanding the scope of these actions to reach children that are currently out of school could have longer-term impact.

- Rethinking distance education provision to reach girls and children with disabilities. This could involve additional funding and support to education providers for the use of assistive technologies; provision of targeted learning materials for girls in poorest households; as well as working with communities to mobilise support for learning for all.

- Fostering between-sector partnerships and a coordinated response to safeguard the most vulnerable children against covid-19 and wider issues. Health and education partnerships are now crucial not only to teach students about best practices against covid-19 spread, but also to prevent and counteract other risks increasingly faced by the most vulnerable during lockdown. Countries cannot lose sight of comprehensive sexuality education programmes adapted for all learners, and renewed need for investments in cross-sector partnerships and safeguarding against gender-based domestic and sexual violence.

- Supporting teachers and head teachers in supporting inclusive learning in their classrooms. Learning for all cannot happen without teachers and head teachers. As students return to classrooms teachers will need support to adapt learning materials to best suit all students, especially if lockdown led to interruptions in learning. For governments, this might mean supporting teachers’ flexibility and autonomy in: adapting the curriculum, re-focusing practices on fostering resilience and socio-emotional learning or revising assessment and learning timelines.

Actions taken in the current crisis need to be long-term measures rather than stop-gap responses. While the grave challenges the crisis presents for the sector have no single cure, they could prove to be a catalyst for the emergence of more resilient and inclusive education systems.

[i] Baker, M. (2013). ‘Industrial Actions in Schools: Strikes and Student Achievement’. The Canadian Journal of Economics, 46(3), 1014–1036.

[ii] Montebruno, P. (Forthcoming). ‘Disrupted Schooling: Impacts on Achievement from the Chilean school occupations’. CEP Discussion Papers, Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science.