This blog was written by Alfonso Accinelli, the former Director of Technological Innovation for Education at the Ministry of Education of Peru.

On March 15th 2020, Peru was among the first countries in the Americas to declare a national lockdown to prevent the spread of the COVID-19 virus, including school closures. Only a few days earlier, the Ministry of Education (MoE) had reprogrammed the start of the 2020 school year from March 16th to March 30th. Even though the national lockdown was declared for only 15 days, based on the experience of other countries, it was highly likely that it would be extended for a much longer period. Therefore, a team at the MoE gathered to design a strategy to provide remote education in the context of a national health emergency and lockdown.

Where to start when faced with an exceptional challenge?

Where to start when faced with an exceptional challenge?

The strategy was built around the restrictions and opportunities of the national lockdown. First, it had to reach the millions of students’ homes with what they had available. The internet only reaches about 40% of households and both radio and TV over 80%. Therefore, to reach the most students, the strategy had to use all three media outlets available from Monday to Friday. Moreover, to avoid an increase in educational inequalities, all education modalities should be considered in the strategy, such as special, adult and inter-cultural education.

Second, the learning experience would be rooted in Peru’s competence-based curriculum. The lessons would be developed or curated by the MoE and imparted using the three channels directly to the students’ homes. Students were not expected to passively interact with the media. Instead, each lesson was designed for students to do in their homes, interacting with their families and environment and using a portfolio of evidence to showcase their work. Besides academic contents for subjects such as language and math, topics related to the emergency context were included: information about the COVID-19 virus, self-care and socio-emotional skills to deal with isolation, physical activity and arts, among others.

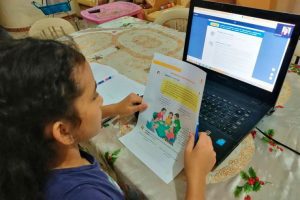

Since these educational experiences are one-way, teachers would have to communicate and provide feedback to their students and their families through other means, including telephone calls, SMS and social media. Teachers would receive online training and orientations to do so. Parents and other family members would be required to mediate the learning of younger children in their homes and older students will be able to study independently.

Since these educational experiences are one-way, teachers would have to communicate and provide feedback to their students and their families through other means, including telephone calls, SMS and social media. Teachers would receive online training and orientations to do so. Parents and other family members would be required to mediate the learning of younger children in their homes and older students will be able to study independently.

Last, the strategy had to be running in just a few weeks and be able to continue to operate for many more weeks or even months. Because of this, we decided for an agile design approach. The strategy would launch with the minimum required, content would be developed on a weekly basis and improvement or additional content would be added in each media channel as the strategy unfolded.

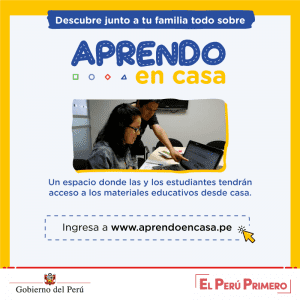

Aprendo en casa: A joint effort to guarantee access to education

The magnitude of the challenge called for almost everyone at the MoE to work at an accelerated velocity to support the strategy. Still, the efforts of the MoE alone would have been insufficient. Several allies from the private and public sector were asked to help implement the strategy. Many shared content for TV or provided free access to their educational platforms. All four internet carriers agreed to free their users’ data plans to access the strategy’s website and provided free SMS to inform families and teachers about the strategy.

Other public sector institutions played a critical role. Another Ministry provided the Cloud space to store the strategy’s new website and the national public TV and radio stations provided several hours each day in their listing for the MoE to run their educational programmes. The four main private TV stations agreed to broadcast a special daily segment for the secondary education seniors. Also, over 300 regional and local radio stations joined the initiative to share the radio lessons in Spanish and nine additional indigenous languages.

As a result, on April 1st, the remote learning strategy Aprendo en casa (I learn from home) was officially approved and on April 6th, it was launched, reaching millions of households via radio, TV and the web www.aprendoencasa.pe. As of the first week of June, it has run continuously for 10 weeks, improving the scope of the programmes each week, and will continue to do so during the closure of schools. Once face-to-face education starts over again, the strategy will complement classroom education.

As a result, on April 1st, the remote learning strategy Aprendo en casa (I learn from home) was officially approved and on April 6th, it was launched, reaching millions of households via radio, TV and the web www.aprendoencasa.pe. As of the first week of June, it has run continuously for 10 weeks, improving the scope of the programmes each week, and will continue to do so during the closure of schools. Once face-to-face education starts over again, the strategy will complement classroom education.

The strategy was an unprecedented success for the Peruvian education system, especially considering the circumstances. It has proven that with the right strategy and the support and commitment from within and outside the MoE, quick and effective policies can be implemented. However, there remain important challenges ahead:

- The strategy has not reached about 10% of the student population. There is a new initiative to provide them with tablets, but is unlikely they will reach all of the at-need students and their educational impact seems very limited.

- There are still several aspects of the strategy that need improvement: the homologation (official certification) of the radio, TV and internet weekly contents or how to strengthen family and student-teacher interactions, among others.

- Finally, there is no clear path as to how the transition from remote education to classroom education will be. In particular, there are questions about if and how the distance education strategy will continue when it does not have all of the MoE’s workforce to support it.

Photos: Published by “El Peruano”, Peru’s official government newspaper, on April 7th, 2020. https://elperuano.pe/noticia-aprendo-casa-escolares-reciben-entusiasmo-clases-virtuales-94079.aspx