This article was written by Jerry Mindes, who leads the Secretariat of the Inclusive Education Collaborative, an influencing platform established earlier this year, and is the US-based Senior Advisor to Leonard Cheshire, which advances disability inclusive development in Asia and Africa.

Last October, I facilitated a meeting of 20-plus education and inclusive education advocates and practitioners, where the following question was discussed:

Do global education results frameworks and metrics advance or impede progress toward achieving inclusive education goals and using inclusive education methodologies?

Among other conversations and events, the discussion that took place at that meeting inspired me to join the recent webinar on Ethics in International Development and Education, hosted by UKFIET on November 24, 2020. I wanted to see if the very design and intended outcomes of education interventions would be viewed through an ethics lens. What I observed is something most of us have known for many years: there is a lot to talk about when it comes to ethics in international development and education. Among the topics that surfaced were vestiges of colonialism, misogyny, ethics in the conduct of research, and yes, ethical concerns regarding the intended beneficiaries of education assistance and the results frameworks we use to measure progress. This blog will amplify this last topic.

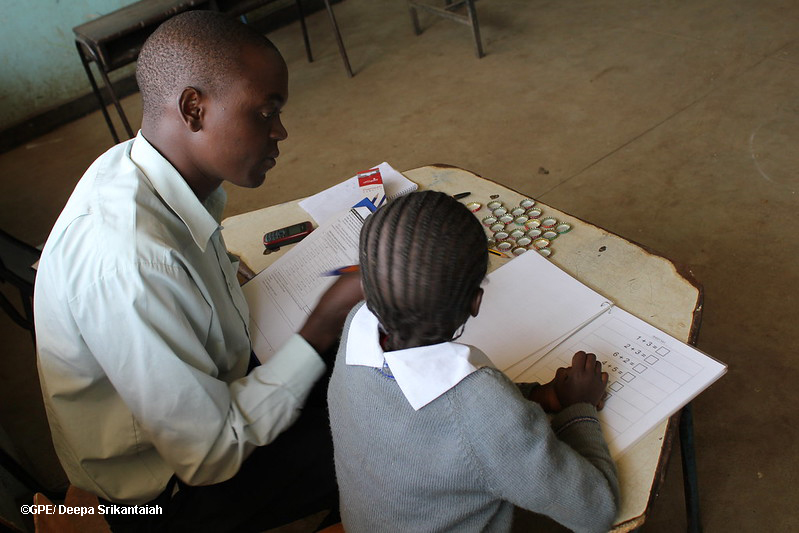

The 2019 meeting began with a review of key “results frameworks” used by global education donors including the US Agency for International Development (USAID), the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), and the World Bank. The group also reviewed the key official indicators for Sustainable Development Goal 4. As part of this review, it was determined that most interventions are measuring the extent to which students achieve specific grade level learning benchmarks. This is precisely the indicator assigned to SDG Goal 4.1. This pattern is found in USAID work in Early Grade Reading and among GPE’s 37 indicators, which lists learning outcome indicators are “core,” and indicators counting out-of-school children are “non-core.”

The group also discussed the World Bank indicator, presented via this tweet from the World Bank Education Group: “Can we in 20 years reduce the number of 10-year old students who cannot read a paragraph to zero?”

The assembled experts and practitioners then discussed the following questions:

- What are the intended and unintended consequences of these results frameworks?

- Do these results frameworks result in there being “winners” and “losers”?

We observed that utilising grade-level indicators focuses attention – and money – on children at the cusp of achieving the targeted goal. This is intensified when donors offer financial incentives for projects meeting those benchmarks. This focus on “children on the cusp” is further exacerbated when we measure results only within the lifespan of a three to five-year project. Projects that move forward only a portion of the student body are not designed to tackle problems that may take 20 years or more to solve, like decreasing the number of out-of-school children to zero and making education systems truly inclusive.

Our group next worked to identify indicators that would advance the goals and methods of inclusive education, thus addressing the learning needs for all children. The group reached broad agreement on the following metrics:

- Are investments moving forward the bottom quintile of students?

- Are investments reducing the number of out-of-school children?

- Are we working with governments and public officials to lengthen their planning and measuring cycles to 20-30 years?

During the discussion leading up to the identification of the metrics above, the group raised several points:

- There was widespread agreement that metrics should measure if all children are improving towards individual learning goals, even if some or many are not reaching grade-level standards.

- If progress is being made in improving learning outcomes for children in the bottom quintile of student performance, then the methods of inclusive education – including differentiated instruction – are likely in use.

- If progress is being made in reducing the number of out-of-school children, then the investment is addressing key issues related to the right to an equitable and inclusive education.

- If governments and public officials are supported in lengthening planning cycles, then they are more likely to be developing strategies to address long-term goals and real systems change. Such an indicator would acknowledge that achieving long-term goals such as universal inclusive education will take many consecutive project cycles

This discussion was buttressed by my learning about the 2019 book “An Optimist’s Telescope” by Bina Venkataraman. In her book, Venkataraman notes that individuals running households, businesses, associations, organisations, and national and international efforts to reduce poverty or address climate change tend to measure what they can see, and often fail to align short-term metrics with long-term goals.

In applying Venkataraman’s theory to our work in international development and education, we can have more discussion about the intended and unintended consequences of our investments, and be more proactive in viewing our work through the ethics lens that the UKFIET session was so correct to advance.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks