This article was written by Timothy Kinoti, World University Service Canada. It was originally published on the Humanitarian Education Accelerator blog on 10 June 2020.

As schools around Kenya, just like the rest of the world have closed due to coronavirus (COVID-19), many institutions and schools are implementing their distance learning contingency plans. This has called for connecting students and teachers through online platforms and tools. The Ministry of Education and the Kenya Institute of Curriculum Development (KICD) are partnering with broadcasting service providers to deliver educational content via television and radio during dedicated hours. As such, increasingly the teachers and parents have had to quickly adapt to teaching in this new reality to ensure that students engage in learning.

The majority of the learners in low-income countries are struggling with access to internet connectivity hence hindering access to learning via online platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams among other preferred options. Access to phones or even radio is another major issue in such settings. There is a high probability and risk of leaving many learners behind over time and the education in-equalities will grow as a result of the COVID-19 situation.

The majority of the learners in low-income countries are struggling with access to internet connectivity hence hindering access to learning via online platforms like Zoom and Microsoft Teams among other preferred options. Access to phones or even radio is another major issue in such settings. There is a high probability and risk of leaving many learners behind over time and the education in-equalities will grow as a result of the COVID-19 situation.

Various online applications such as Recap: Video Response and Reflection for Education, WURRLYedu, and Screencastify are excellent solutions reaching students of different locations around the world. However, this only works best in urban well-developed countries where we have access to connectivity. Locally (in Kenya), we have the M-shule, Eneza, Mwalimoo and Longhorn e-learning among others that have been used commonly by urban learners. Those in highly marginalised segments have no access to the relevant hardware or software with which to access the online content in the country still, hence always left out in the competitive global platform. Despite the rapid intervention applications, the challenge remains that teachers are struggling to monitor and assess the quality of learning that is happening at home, without learners having access to hardware and connectivity that might allow for online assessments.

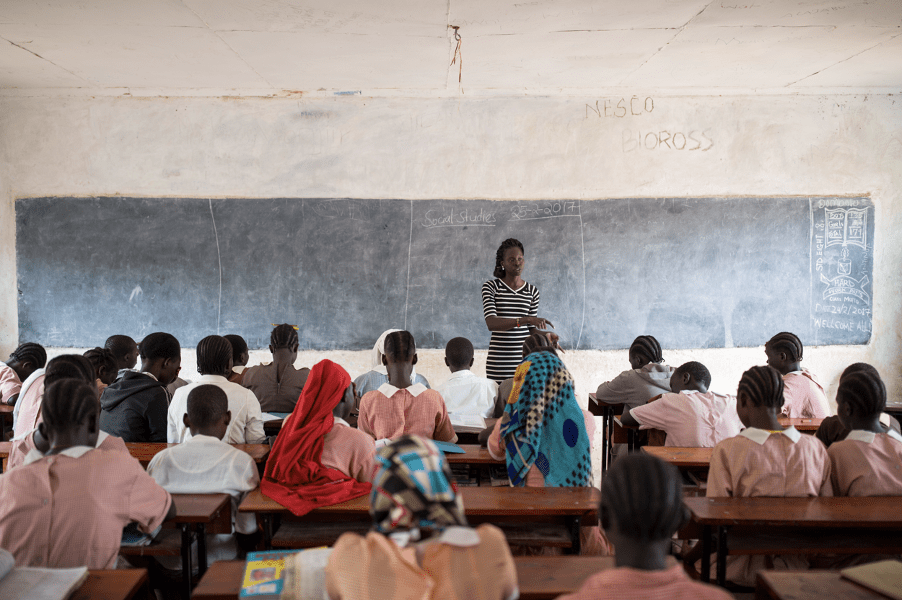

There is a need for the co-creation of workable solutions with the teachers in the low resourced areas as the teachers know best what might work in their context, and the limitations their students face. For example, the World University Service of Canada (WUSC) and Windle International Kenya (WIK) implement education programs in Northern Kenya covering the Dadaab and Kakuma refugee and host schools. Some of their co-created Covid-19 response education interventions focus on community interventions and girl centered interventions to support learning while at home, namely;

- Supporting families economically through cash transfer: in addition to their usual cash intervention, WUSC/WIK scaled up the number of beneficiaries and amounts disbursed to the beneficiaries. The purpose of the scale up is to help learners access needed commodities for health purposes e.g. soap, buy food, sanitary materials while also providing additional funds to purchase learning materials while at home, such as books. The families can use the funds to purchase any additional hardware to access online learning.

- Re-orientation of the radio programs, to address the importance of maintaining learning while at home; safeguarding issues, and discussions on continuously engaging men and boys to support girls’ education while at home. In Northern Kenya, girls are more at risk while at home and maybe engrossed on household chores and leave out on the school work.

- Scaling up the use of Eneza EdTech among the learners. WUSC/WIK is running sensitisation sessions to get parents to allow their children to use their phones for Eneza and recognize Shupavu291 as a legitimate way to maintain learning while school is out. Eneza enables access to revision materials that would be crucial for learners especially now when they cannot access school libraries. It is a potential solution for parents who cannot afford to buy textbooks or other revision materials.

Possible solutions to assessing learners in low-income countries

With this new normal of learning taking shape, as educationists, we are increasingly asking ourselves questions on how can we assess the learners? Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, all forms of learning assessment relied on the physical presence of learners in school, and the assessment tests administered by the teacher and timed for every subject. However, currently learning is happening remotely and with the support of the parents and or guardians who have taken up the role of the teacher at home have to fit into the shoes of the school teacher.

There are a number of assessment options that can be explored by educationists, that range from low tech and low cost to higher tech and high cost.

1) Use of SMS chats WhatsApp chat groups: a majority of low-income households have access to a form of mobile phone: feature or smartphones. Short assessment questions can be sent to the learners, however there might be the risk that caretakers and older siblings will help the learners respond to them, so may not accurately reflect knowledge gained.

2) Direct phone calls: similarly, teachers can engage with the learners on phone calls and run verbal assessment questions. This approach can be appropriate to get quick rapid responses and views from the learners on diverse subjects.

3) Online games that test vocabulary, grammar and math skills. These can be easily downloaded on smartphones and teachers can have access to the back office to verify individual student scores. Though these do come at a cost, there are some that have provided free access during COVID-19 school closures.

4) Photos of homework sent to the teachers

5) Parents administering tests and sending results to teachers

Though all the above options should be used in combination, there is also potential to develop an assessment toolkit that can be adapted to specific country curriculums and administered remotely and effectively in measuring time spent in certain tasks. This will streamline the assessment for the teacher, and can also be used and adapted once school’s reopen.

Challenges with Distance Education

Despite the above-mentioned possible options, there are potential challenges that need to be factored along the way of implementation.

- Language barriers: Most of the learners in the low-income remote settings have serious challenges with the language of instruction. Needless to mention illiteracy levels that are high with their parents or guardians who would be expected to support them in homeschooling.

- Access to phones/tablets/computers by learners: As noted earlier, a number of learners in this low-income setting are likely to be left out of the digital move. A blended approach may be used to reach out to most of the learners in such settings as well.

- Teachers losing their salaries due to school closures: Some of the teachers in such settings are not in the government payroll. They are either hired by NGOs or the school Boards of Management (BOMs). Some of these teachers may be asked to take unpaid leave due to the sustained costs of keeping teachers on payroll with no teaching taking place.

- Teachers need to be trained to use new technologies alongside students: Many teacher’s have not been given the opportunity to refresh their teacher training to incorporate technology into the classroom, and thus have been unable to keep up with technology trends. Similarly, they face challenges on ownership of phones and access to the internet in their localities.

Challenges when School’s Re-Open

Once the school’s resume, teachers may struggle with two key challenges

1) Understanding how learners who have been out of school, without access to distance learning opportunities, will catch up to their appropriate grade/class level of education.

2) Providing assessments for those that have followed distance learning programmes, to determine what knowledge has been retained and where they need to focus a potential condensed curriculum for the remainder of the school year.

Formative assessments will be key to understand the current levels that the learners are at. The above mentioned assessment toolkit may be useful to efficiently assist teacher’s to understand the different learning needs of their students. There are also potential options that can be explored on how best to bring learners up to speed and catch up on time lost. Remedial learning is one of the options that has been implemented by WUSC/WIK for 6 years now in Dadaab and Kakuma refugee camps and host communities.

In 2017/18 WUSC in collaboration with American Institute for Research (AIR) with funding from Humanitarian Education Accelerator (HEA), conducted an impact study on the WUSC/WIK remedial program. The findings showed that there is potential for remedial to boost learning gains for the most marginalised learners under certain conditions like food secure households, but most importantly it became a popular program for learners who wanted to focus catch up classes in certain subjects and be in a less congested classroom environment to boost their confidence (De Hoop et al., 2019). The literature review does show there are different forms of remedial learning and if well implemented, with a focus on areas that learners are struggling with, there is potential for improved learning outcomes in low- and middle-income countries, however, the existing evidence base is small and shows mixed results (Snilstveit et al., 2016; UNICEF Innocenti, 2018).

Once school’s re-open, teachers will need to provide catch up classes, like those offered by the WUSC/WIK Remedial Learning, as they will be key in ensuring that the most vulnerable students are not left further behind.

That is real