This blog was written by Sushan Acharya, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal. For the 2017 UKFIET conference, 23 individuals were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their experience.

Research in the area of women, literacy and health has been dominated by a quantitative narrative, looking at the impact of schooling and formal educational interventions on health indicators, for example, the statistical relationships between women’s literacy rate and fertility, and child and maternal mortality. This has led to a narrow policy focus within adult literacy regarding functional literacy as a vehicle for imparting modern health knowledge and failure to engage with social changes taking place outside the development sector. Therefore there is a need to re-examine the relationship between gender, literacy and health in Nepal, and explore an alternative conceptualisation of literacy as a social practice and health as connected with social justice.

Adult literacy programmes have a long history in Nepal, starting from 1953 with Laubach’s assistance for the government’s mass literacy programme, which focused on reading and writing only. Then in the 1960s, this moved to a functionalist approach, designed to enable women ‘to better perform their traditional ropes as homemakers and childcare takers’ (Acharya, 2004). This emphasis on women’s reproductive roles continues today. Women are the focus, not just because more are non-literate, but also providers consider them to be ‘a more reliable and secure investment’ (Shrestha, 1993). In other words, women’s literacy programmes largely pursue an instrumental objective.

The main literacy approach has been the Freirean-based Naya Goreto (or New Trail – a popular primer developed with inspiration from Freire in the 1970s), using key words and pictures but depoliticised to focus on development messages. The restoration of democracy in 1990 led to a mushrooming of NGOs, many using literacy as an entry point to other development activities. Characteristics include:

- a literacy first approach (literacy classes first, then later other health/agriculture activities)

- reinforcing, rather than challenging, existing gender relations and stereotypes

- no engagement with indigenous values and practices around gender roles (programmes ‘tried to inject value of the mainstream or power holding people, i.e. Brahman and Kshtriya in the case of Nepal’, Acharya, 2004).

Many adult literacy programmes combined health knowledge/information with literacy learning. However, in practice, the literacy facilitators and participants often prioritised reading and writing skills over discussion of health issues (Robinson-Pant, 2001). This was partly because they were also learning in a second language, the facilitators did not have specialist health experience and the primer presented simplistic messages (for example, that a woman should simply persuade her husband to adopt family planning). Moreover, such blending of health and literacy became common practice. The education sector saw it as health programmes and the health sector saw it as literacy programmes.

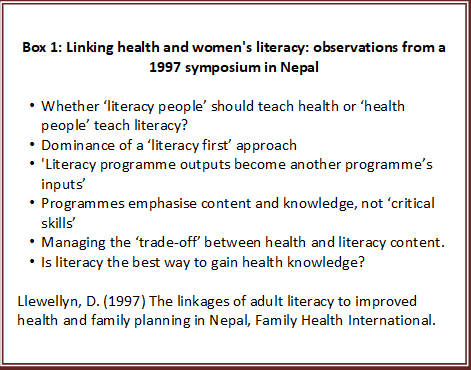

Attempts to integrate literacy and health raised many issues, such as those raised in a symposium in 1997 (see Box 1). These include issues such as: Who determines the health curriculum – policymakers or communities? Functional or transformative literacy learning? Dichotomised relationship between literacy/orality. Therefore, there is a need to revisit the relationship between literacy, health and women’s empowerment through an alternative ideological stance.

Points relevant to health inequalities and learning include:

- multiple literacies and informal learning

- intergenerational learning and indigenous knowledge (not just privileging new Western health knowledge)

- challenging binaries of orality/literacy and literate/illiterate, proposing a continuum

- focusing on literacy learning and literacy mediation outside the classroom.

Health programmes have also tended to take a ‘technical’ approach, focusing on individuals, rather than a rights approach, which has been strongly promoted by WHO, including seeing gender equality as central (WHO, 2006). The recent global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (EWEC, 2015) states commitment to addressing unequal gender norms/stereotypes influencing health policy and services.

The distinction between health education and health promotion is particularly relevant, because health education focuses on the individual client; health promotion engages the whole community in a politicised process of awareness-raising and mobilisation to directly address the social determinants of health. Health promotion has a different approach to learning – ‘asset based’, seeing adults as participants, critical thinkers and agents of change (Hill, 2016), rather than deficit approach. Health workers have multiple roles as educators and build on informal learning, different knowledge and develop critical health literacy skills.

By investigating what kind of literacy and health education ideologies informed policy and practices, the following challenges have been found, which have wider implications for the SDG agenda:

- Health education relied more on oral facilitation, in contrast to functional literacy, but both methods prioritised ‘preaching’ messages, not critical pedagogy.

- Neither programme engaged with indigenous beliefs in a positive way.

- Both sectors have shifted from a women-only approach to gender equality, but this needs to be seen in relation to the organisation (with gendered roles of female Community Health Worker volunteers), and a more complex picture of change that involves men too.

- Health and literacy programmes are still based on a simplistic understanding/depiction of gendered roles and relations, and does not draw on informal learning sources, such as mobile phones, social media, or migration.

References:

Acharya, S. (2004). Democracy, Gender Equality and Women’s Literacy: Experience from Nepal. UNESCO Kathmandu Series of Monographs and Working papers No. 1. Kathmandu: UNESCO.

EWEC (Every Woman Every Child) (2015). The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health (2016-2030), Survive, Thrive, Transform, Geneva: WHO.

http://www.who.int/life-course/partners/global-strategy/en/

Hill, L. (2016). Interactive Influences on Health and Adult Education, New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, No. 149, Spring 2016.

http://www.voced.edu.au/content/ngv%3A72846

Llewellyn, D. (1997). The linkages of adult literacy to improved health and family planning in Nepal, Family Health International, North Carolina, June 2 1997.

Robinson-Pant, A. (2001). Why eat green cucumber at the time of dying? Exploring the link between women’s’ literacy and development: A Nepal perspective. Hamburg: UNESCO Institute of Education.

Shrestha, C. (1993). A study of supply and Demand of Non-formal Education in Nepal, Kathmandu: World Education.

World Health Organization (2006). Constitution of the World Health Organization.