Steve Packer, UKFIET Board of Trustees, and Ian MacAuslan, Oxford Policy Management

It is good news that the International Development Committee (IDC) report on DFID and its education activities has been published on 21 November 2017. Interrupted by the June 2017 election, there were doubts that the Committee’s work would be completed. Thankfully, and with further evidence from DFID, the report makes an important statement about the need to accord greater priority to education in DFID programming, ahead of the Department’s ‘refresh’ of its education policy framework early in 2018.

The report assesses whether DFID’s official support for global education is financed and programmed appropriately to help to meet the goal of leaving no one behind. Its introduction sets out the IDC’s overall conclusion: The Department needs to demonstrate a long-term, sustainable commitment to support access to inclusive, quality education in all its partner countries. The role of education in underpinning all other aspects of development should make it a top priority for the UK. Within that, DFID’s clear commitment to the poorest makes a focus on the most marginalised children the most appropriate policy response.

The report tests DFID’s record and forward thinking in three related areas: financing global education, improving access to education, and improving the quality and equity of education.

Financing global education

On finance, the report promotes three, well-rehearsed arguments. First – but not in the order of the report, and somewhat hidden in its text – it notes that ODA spending on education as a proportion of total spending on education in developing countries is less than 4%. This fact is surely the core of the SDG4 challenge. But rather tamely, the report recommends that the UK Government should, wherever possible, use its influence with partner countries to encourage greater domestic spending on education. Experience suggests that support for governance and public expenditure reforms and initiatives will be more productive than education programmes in this regard.

Second, the report concludes that education receives too little of UK ODA spend. The report tries – with some difficulty, given the increase in aid through UK government departments other than DFID – to map trends in education spend in recent years. It notes a drop from 10.14% (2011) to 7.17% of total net UK ODA spend in 2015. The most recent DFID aid statistics (issued after the publication of the report) show a rise in education spend from £652 million in 2015 to £964 million in 2016; this is accounted for, in part, by a contribution of £106 million to the Global Partnership for Education (GPE). Education constituted 11.3% of bilateral spend in 2016; the fifth largest sector. But it is much more difficult to track education spend through multilateral organisations. Overall, it is a weakness that no attempt is made to disaggregate expenditure in terms of sub-sector or in relation to the most marginalised and disadvantaged. The report’s general injunction is for a significant increase in the amount of UK ODA allocated to education over the course of the next spending review period within a value for money (VfM) framework, but it does not elaborate on what this means for effective ways of working. And the report rightly enjoins DFID and partners to provide better justifications of education spend in language amenable to politicians.

Third, the IDC cites the important role that the UK can and should play in maximising the benefits of multilateral funding mechanisms for education. It is supportive of the GPE, arguing, a little generously, that the partnership has a unique approach to improving the education systems in developing countries. It recommends that DFID should agree to the full financial contribution requested by GPE at the next replenishment whilst encouraging other donors to step forward too. It is more muted on the International Financing Facility for Education (IFFEd), concluding that DFID should support the IFFEd, as an additional mechanism for leveraging funding into the provision of global education.

The Committee believes that there is a golden opportunity in DFID’s refreshed education policy to affirm its commitment to increased and sustainable levels of funding for global education and demonstrate how it will work across Government to achieve results for education around the world. The policy framework is very unlikely to include spending commitments, but it could usefully put some more flesh on the bones of the Committee’s three areas of financing imperatives.

Improving access to education

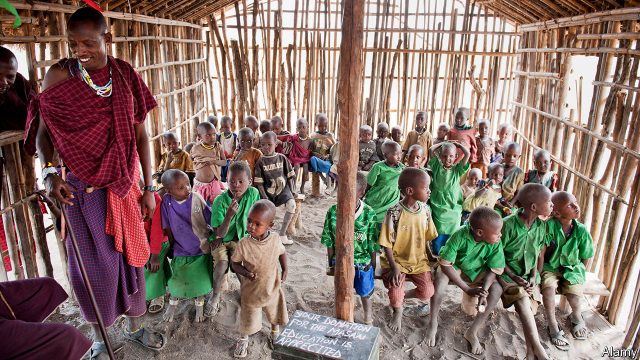

As is customary, access and quality are treated separately: a false dichotomy if policy and practice is to have coherence. The sections under access on early learning and private sector schooling make this point clearly. That said, the chapter on access focuses rightly on the most marginalised and the hardest to reach. It cites Lord Burt … this is what we [the UK Government] believe our remit is. Girls and young women, children caught up in emergencies, and disabled young people are identified as requiring targeted intervention. The fact that most of these children suffer from multiple disadvantage comes through implicitly. In reality, responsive programming requires a comprehensive cross-sector approach.

DFID is encouraged to develop country-specific strategies for marginalised girls’ education, based on detailed knowledge of the barriers in each context and learning from successful interventions. It is asked to move from its work on its disability framework (DFID 2014/15) to shine a light on the needs of disabled children and ensure this [the framework] is being implemented across all DFID programmes. And on emergencies, the report argues, rightly, the need for a long-term, integrated strategy for supporting education in emergencies; getting affected children back into structured learning environments as a priority, alongside clean water, food, sanitation and shelter. It will be a surprise if the new policy framework does not address these recommendations head on. They lie at the heart of no one left behind.

The chapter on access also examines the role of early learning and the role of non-state providers. DFID is a late convert to early childhood care and education (ECCE) but is now encouraged to invest more in pre-primary education, bilaterally and multilaterally. The section on private education identifies the need for much stronger evidence on the benefits of private sector schooling for the most disadvantaged. Citing an ICAI report it notes … DFID lacks the evidence to make informed judgments as to what combination [working with governments and/or private providers] offers the best value for money in which contexts. The report spends some time examining the case of Bridge Schools, which are under much public scrutiny, but a side effect of this focus is a failure to take a more nuanced looked at the extraordinary range of non-governmental schooling. In particular, the report underplays the vital roles that community- and faith-based organisations, not-for-profits and some private organisations play in expanding access to quality and context-specific education for marginalised groups. And in turn, it risks neglecting the critical importance of strengthening governments’ abilities to ensure they get the best out of the non-government sector.

Tucked away in the middle of the chapter is a very short section on VfM; an odd location, as this topic cuts across all of DFID education programming. However, the IDC rightly stresses the importance of DFID clarifying and ensuring that its value for money approach is fit for purpose when targeting the most marginalised children. This is not straightforward: education could learn from how other sectors measure – and therefore justify – the additional ‘value’ of reaching marginalised groups

Improving the quality and equity of education

Pedantically, the heading of Chapter 4, ‘Improving the Quality and Equity of Education’ could be better stated as ‘Improving equitable access to meaningful learning opportunities for all’. ‘Quality’ and ‘Equity’ run the danger of becoming unhelpful catch-all terms. It is a remarkably brief section for such weighty subject matter. It has very little to say about teaching and learning, about schools and their teachers and communities; and about learning strategies for the most disadvantaged. It has – but very briefly – sensible things to say about systemic reform and politically-informed programming. It underscores the importance of data and research (though not, unfortunately anything about long-term DFID education programme evaluation). It recognises the need for specialist in-house DFID education sector expertise. It wisely recommends continued support for the Global Education Monitoring Report. Yet overall, the story line is much weaker than the section on access, partly because learning strategies are dealt with, at least in part, within Chapter 3.

The IDC report is welcome. There has been a paucity of public debate on DFID education policy for a while. The position paper of 2013 is the last substantive statement. The evidence received by the Committee, orally and through written submissions (including from UKFIET) is of considerable value in itself. Its focus on the most marginalised is right and forceful. But the report is almost entirely concerned with basic schooling, including, rightly, pre-primary. It argues for a systems-wide approach but is largely quiet on skills for livelihoods. It acknowledges cross-sector programming but fails to examine the how beyond the what. We now wait to see whether the report’s argument carries weight in the DFID education policy ‘refresh’.