This blog was written by Dr Geneviève Greer, drawing on reflections from the UKFIET 2025 conference and doctoral research on the political economy of education in conflict and crisis. Dr Greer is an independent interdisciplinary researcher and consultant, and former Research Fellow with the International Rescue Committee’s Airbel Impact Lab and M&E Specialist with Save the Children. A recent PhD graduate from Ulster University’s UNESCO Centre, her research explored the political economy and injustices of education programme design in conflict and crisis contexts using systems thinking and Q-methodology. Her work bridges education, health and climate, with a commitment to social and environmental justice.

The moment of discomfort

At this year’s UKFIET conference on Mobilising Partnerships, I presented findings from my PhD research, The Balancing Act, in the session Between Influence and Agency: Unpacking Power in Education Programme Design and Implementation.

Yet the moments that lingered most came not from my own session, but from the opening and BAICE presidential address plenaries.

On the first day, Professor Ahmed Kamal Junina from Al-Aqsa University in Gaza appeared on the large screen above us, joining virtually – perhaps through the very same Amazon Web Services (AWS) infrastructure that partly sponsored the event. His projected face reminded us of the fragility of connection in a world where the same digital threads that sustain life and learning can also sustain surveillance and war.

The next day, after Professor Arathi Sriprakash’s powerful BAICE presidential address plenary on Reparative Justice, a participant stood and asked a question many had been thinking: “Why was AWS chosen as a conference sponsor, when AWS is accused of complicity in the genocide in Gaza?”

The hall fell silent. It was one of the most visceral, uncomfortable moments I have witnessed at a conference – exposing tensions at the heart of the week’s theme. In a world woven together by the digital and the geopolitical, how do we mobilise partnerships without reproducing injustice?

Implication and complicity

In my doctoral research, I explored how education practitioners navigate power between equity and efficiency, influence and agency – within global systems that are themselves unjust. What unfolded in that plenary mirrored those same tensions.

Most of us are neither victims nor perpetrators but implicated: enmeshed in structures that perpetuate harm even as we strive to resist it. One participant declared, “I am implicated.” Another asked, “How many of us have an Amazon account?”

AWS hosts around one third of the world’s cloud infrastructure. Netflix, Google and humanitarian data platforms all rely on it. The same servers that amplify Gazan voices also power the machinery of war. “Amazon, Google and Microsoft fuel Israeli military aggression” whilst contracts enable surveillance. To what extent, in using and paying for these same services, are we all implicated?

This paradox extends beyond technology. When I worked with Save the Children in the 2010s, teams were dedicated to prospect research – scrutinising potential corporate donors. The rules were once clear: no tobacco, alcohol, arms, pornography or extractives. Yet boundaries are more blurred in today’s tangled web of investments and technology use. As partnerships between academia, NGOs, governments and corporations multiply, ethical dilemmas have only intensified.

From equity to ethics: re-thinking partnership

UKFIET’s organisers – largely volunteers – faced difficult choices. Their stated intention was to advance equity by offering more bursaries than ever to Global South researchers. Yet, as one participant challenged, Global South colleagues should not be used as a cloak for partnerships that risk harm.

The conference did explore, though not always explicitly, what “mobilising partnerships” means as a political process. Political economy analysis concerns “the interaction of political and economic processes in a society — the distribution of power and wealth between different groups and individuals, and the processes that create, sustain and transform these relationships over time.”

Partnerships, viewed through this lens, are not neutral arrangements but political relationships – shaped by competing interests, histories of exclusion, and unequal access to resources. Traditional due diligence, focused on compliance and reputational risk, is no longer enough. We need a political-economy-informed due diligence that interrogates power, voice and relational ethics.

The BANI framework describes the world as Brittle, Anxious, Non-linear and Incomprehensible. It offers another potentially useful lens for partnership management. In a BANI world, even apparently-stable institutions can fracture overnight, as the recent collapse of USAID illustrated.

Partnerships themselves are brittle (vulnerable to shocks), anxious (fearful of reputational harm), non-linear (shaped by shifting alliances), and often incomprehensible (entangled in opaque hierarchies). Rather than treating due diligence as a static “Go/No-Go” checklist, perhaps it could be reimagined as a more open and transparent dialogue – one that acknowledges competing pressures and seeks to balance principle with pragmatism.

After all, partnerships are never just financial transactions; they are moral too. For corporations, alignment with education and justice movements offers moral capital and reputational gain. Yet too often, these relationships risk becoming extractive: charities and researchers provide legitimacy while funders reap the public-relations dividend.

A more balanced approach would not reject corporate partnerships outright but engage with them critically and transparently – recognising that value and influence flow both ways. This is not about purity, but about honesty: naming the exchange and ensuring that those whose causes give partnerships their moral weight are meaningfully included in decisions about how they are formed.

Reparative justice and epistemic inequity

Arathi Sriprakash’s reparative-justice plenary brought this discomfort into sharp focus. She urged us to move beyond participation toward reparation – asking not only who is included, but who benefits, who decides and who repairs historical and ongoing harm.

As Maha Shuayb has shown, inequities in research partnerships remain stark: of 125 grants in global education and displacement research, 88% were held in the Global North. Despite a proliferation of ethical guidelines, practice remains deeply uneven.

During the plenary, as UKFIET representatives made their way to the stage to respond, the moment felt troubling. Arathi noted that this was not what she had intended. What unfolded did not feel like reparative care but created a dynamic of accusation and defence – illustrating how difficult it is to practise participatory care when accountability, politics and authority collide. Yet Arathi succeeded in challenging us to confront discomfort, reveal the bare threads of structural injustice, and perhaps begin repair.

A taxonomy of interaction with injustices

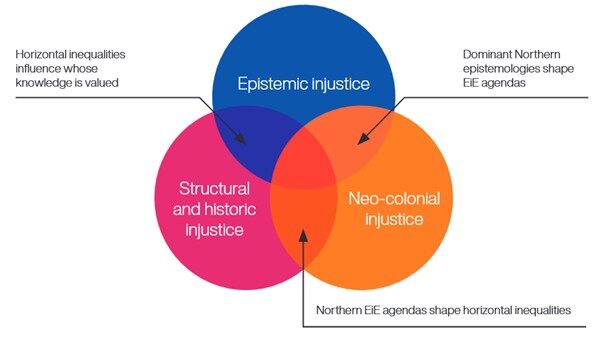

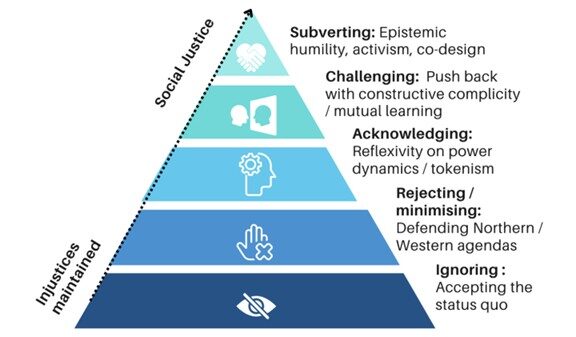

In my PhD, I adapted the Injustices Model (Figure 1) to develop a taxonomy (Figure 2) illustrating how education practitioners and researchers interact with structural, neo-colonial, epistemic and historic injustices within unequal systems, in the central triangle where these injustices intersect.

Figure 1 Shanks & Paulson (2023) Injustices Model

Figure 2. Ways education programme designers in conflict and crisis interact with injustices (Greer, 2025).

The taxonomy reveals five modes of interaction with injustices – ranging from ignoring injustice to actively subverting it.

- Ignoring injustice – turning a blind eye. Maintaining the status quo, often for survival or stability. The most common interaction. Many practitioners described feeling “trapped” within institutional norms, turning a blind eye to injustice as ‘just the way things are.’

- Rejecting/minimising injustice. Some defend dominant Northern agendas under the banner of “doing good” – for instance, citing Global South bursaries as justification for accepting corporate sponsorship.

- Acknowledging injustice – critical awareness. Practitioners reflect on bias and privilege, recognising themselves as implicated subjects.

- Challenging injustice – constructive complicity. Others push back within systems while recognising their own entanglement. “Constructive complicity” involves acts of “defensive dissent”: speaking up, reframing programmes or leveraging resources for equity – while remaining reflexive about the duality of complicity and dissent.

- Subverting injustice – activism (towards repair). Some practitioners actively disrupt systemic hierarchies through anti-oppressive practice, epistemic humility and co-design. They seek to reverse the “white gaze” and ensure those closest to the issues define priorities – embodying the principle of “nothing for them without them.”

Across the taxonomy, movement is dynamic and situational. Most of us move fluidly between these levels, sometimes daily. The UKFIET plenary reminded me how hard it is to move beyond the two lower tiers. To question a system that sustains one’s presence, salary, status or safety is an act of courage; yet activism without fear of retribution is itself a privilege, linked to freedom of speech and economic security. ‘Injustice is not an inevitability in reparative futures of education: these are new, if challenging, horizons of theory and practice for the field.’

Stories, platforms and technological entanglement

Whose stories are heard – and how? Palestinian youth use social media to witness and resist erasure, even as those same platforms sit within infrastructures of power. Digital connections can amplify voice and reproduce dependency at once.

Epistemic injustice arises when certain knowledges are discounted because of who expresses them. Ahmed Kamal Junina, projected on the conference screen, was both visible and marginalised – seen but not present. The reliance on AWS infrastructure demonstrates the uneasy recognition that technologies enabling connection also reinforce dependency and surveillance. Digital media amplifies voice – yet embeds those voices in the infrastructures of power they contest.

If we are serious about reparative justice, we must attend not just to who speaks, but to how we listen, and what forms of action – or inaction – our listening enables. Even in virtual spaces, power can be reproduced through “technical epistemicide”: muted microphones, unequal bandwidths or connection speed.

AI intensifies these questions. It already shapes analysis and writing in our sector; its apparent efficiency obscures issues of data ownership, bias and erasure. Sociodigital futures of education are grounded in reparation, sovereignty, care and democratisation – reminding us that digital partnerships and infrastructures are never neutral.

Learning in an “incomprehensible” era

This year’s UKFIET conference felt emotionally charged. Tears in multiple sessions signalled how hard it is to work and learn in an “incomprehensible” era. One standout session shared evidence-informed, arts-based approaches to supporting psychosocial wellbeing for children, youth and caregivers living with adversity. Having just completed an evidence review on mental health and wellbeing in and through education in conflict and crisis, the book resonated: a reminder that rigorous, long-term research and partnership can draw strength from both science and the arts.

In a session on epistemic justice, we also named the weight of privilege embedded in places and spaces. Looking around Oxford’s Examination Schools, built on centuries of exclusion and colonial exploitation, I remembered a fellow state school educated friend’s remark: “Is it any wonder the privately educated feel so at home here? They just swap the quad at Winchester for the quad at Oxford, for the quad at Westminster.” Space is not neutral. Power endures through familiar spaces.

A call for moral reflexivity

What I took from the UKFIET 2025 conference is not that partnerships are inherently good or bad, but that mobilising them requires moral reflexivity. As Arathi Sriprakash asked, “Can we repair a system that still continues to harm?”

If systems thinking is to be transformative, it must map not only causal loops but moral loops – tracing how our actions reinforce or disrupt injustice. Structural, epistemic and neo-colonial injustices live within our funding calls, sponsorships and silences. As Arathi noted, in the words of one of her colleagues: “Racism doesn’t always shout – sometimes it whispers through paperwork.” She spoke of reparative futures and small, intentional acts of redress. Yet when UKFIET representatives responded that the sponsorship did not influence themes, the moment revealed how difficult it is to embody care in confrontation.

This reflexive account is my story. But there were over 400 people in those plenary sessions feeling the weight of the ‘elephant in the room.’ As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie reminds us, “there is danger in a single story.” Beside me, a researcher from Afghanistan whispered: “My father died supporting girls’ education, but some girls also died because they were implicated in the education he provided.” Education is always political; partnerships are never neutral.

Epistemic humility depends on polyphony – on listening to many, intersecting stories. My research sought to amplify such a polyphony of practitioner voices – thirty participants across sixteen countries – revealing four intersecting, shared viewpoints, whose insights both reveal and challenge the status quo.

Perhaps, then, the task is not just to mobilise partnerships, but to approach them with humility as a continual negotiation of mutual benefit and potential injustices – acknowledging that equity and efficiency often pull us in opposite directions. In the ‘incomprehensible’ era there are no easy answers; only an ongoing balancing act.