This blog was written by Chris Millora, Goldsmiths University of London.

On 5th December, the United Nations marked 2026 as the International Volunteer Year – a celebration recognising the vital role volunteers play in achieving sustainable development. For many of us who volunteer, or whose lives have been touched by volunteers, we know that volunteer action is present everywhere and in many moments of need. Volunteering happens not only in formal organisations such as in charities and NGOs but also within communities. Volunteers are often the first responders during environmental disasters and the organisers behind significant campaigns. They are not only extra hands and feet; they are also leaders, including as founders of grassroots organisations.

While much has been written about volunteering’s contributions to societies, there is still a need for a better understanding of the learning dimensions of volunteer action – an area that may be of particular interest to scholars of education and development. I am particularly interested in what has been described as informal learning – learning processes embedded in everyday life, often with little support and structure, yet which have profound impacts on learners’ identities. As we celebrate the International Volunteer Year, I reflect on some important issues surrounding volunteering and learning: what and how do people learn when they volunteer? How do these learning processes impact volunteering experiences?

Volunteering spaces as (informal) learning spaces

Research and experience show that we learn a wide range of skills and knowledge when we volunteer – from communication and organisational skills, to political efficacy and social awareness. These then become pathways to broader social cohesion – such as learning to live together and managing fast-changing stakeholder relationships.

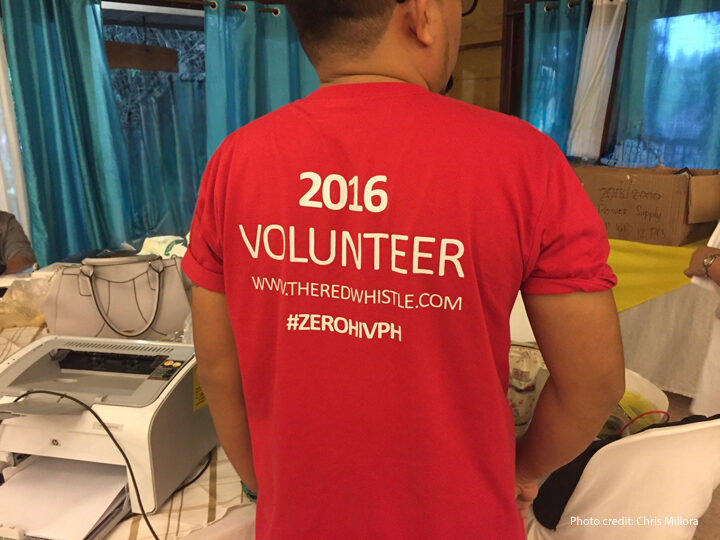

In an African American women’s organisation in the United States, for example, volunteers learn skills such as fundraising, internal administrative processes and relationship building (e.g. working with authorities). In my own research in the Philippines, youth volunteers shared that volunteering deepened their understanding of social issues, while also learning ways to take action in their own communities.

Yet, there remains the challenge of recognising this informal, community-based learning. In a paper on youth volunteering and employability, we found that young people often lacked the vocabulary to describe the skills and knowledge they gained through volunteering as ‘employability’ skills. While some companies acknowledge volunteering as a form of work experience, this is not always the case – despite the sophisticated skills volunteers develop.

Beyond learning outcomes

Beyond the acquisition of skills and knowledge, I found in my research that learning in/through volunteering also becomes a pathway for young people to reimagine their identities. In my long-term ethnographic study in the Philippines, I found youth volunteers – many of whom come from income-poor backgrounds – expressed a sense of surprise that through volunteering, they too can give to others despite having little resources of their own.

Therefore, volunteering is also about learning (more) about oneself and what one can contribute to their community. This can shift how young people understand their social roles, allowing them to see themselves as development actors rather than simply recipients of aid. This is particularly important given persistent narratives in international development that position ‘the poor’ or ‘the marginalised’ as beneficiaries rather than active participants.

Imbalances in volunteering research and evidence

A broader concern relates to how knowledge about volunteering and development is produced and circulated. In a collaborative work with colleagues from South Africa and Mexico, we found persistent inequalities in volunteering research.

This manifests in two key ways. First, through research funding and publishing culture that sees the Global North as being the centre and the Global South as being the periphery of knowledge production. Second, through dominant discourses of volunteering as a formal service delivery emanating from the Global North being applied everywhere despite differences in contexts. This, at times, imposes invisibility on culturally-influenced forms of volunteering, such as bayanihan in the Philippines, that might not ‘fit’ with long-held, formal definitions of what counts as volunteering.

This geopolitics of knowledge production shapes which types of volunteering are recognised, which research is valued, and which perspectives influence policy and practice – including, potentially, decisions relating to commitments towards the International Year of Volunteering.

Closing reflections

This past year, I have been facilitating a series of dialogues with volunteers, stakeholders, volunteer-involving organisations and sector leaders in volunteering for development to develop A Call to Action on the Future of Volunteering – a global manifesto that calls for better recognition, support and safeguarding of volunteers everywhere. As we celebrate 2026 as the International Volunteer Year – how can a learning lens help us understand the role of volunteering in development.

First, an understanding of the learning dimension of volunteering highlights that volunteering does not only benefit societies but the individual volunteers themselves. In the newly released Call to Action, there is a specific action area on the need for better recognition of skills developed through volunteering, such as through certifications, accreditation and micro-credits.

Second, learning in/through volunteering allows volunteers, especially those dominantly considered as ‘marginalised’ to challenge their ‘ascribed’ roles in societies. Through volunteering, they are able to make significant contributions to local issues and challenges – even those that they themselves are experiencing.

Third, a learning lens reveals imbalances in understanding volunteering and perhaps the tendency of volunteering to counterintuitively enhance inequalities in already vulnerable groups. In certain contexts, volunteering runs the risk of being a proxy for ‘cheap labour’, leading to exploitation or over-reliance on community-based support activities.

Despite these challenges, volunteering remains an important ingredient in community solidarity, social cohesion and, in several contexts, survival. As we celebrate the International Volunteer Year, it is important that stakeholders – including academics and educational institutions – contribute to creating an environment where volunteer action is recognised, supported and safeguarded.