This blog was written by M Affan Javed, Regional Head of School Systems, British Council South Asia. Affan presented at the 2025 UKFIET conference and took part in a virtual panel following the conference, relating to the theme of equitable partnerships and cross-cultural collaboration.

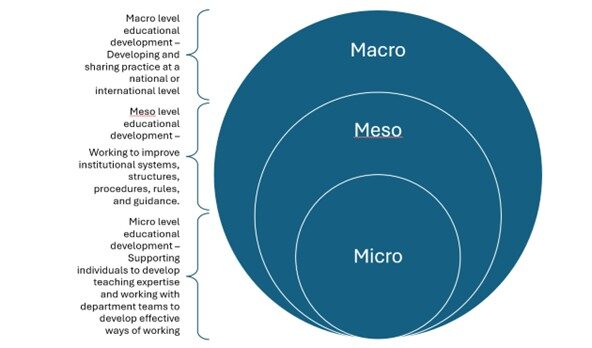

In South Asia, education systems are vast, layered and deeply hierarchical. Across a range of academic disciplines, the structures for Teacher Professional Development (TPD) can be framed as micro (individual), meso (institutional) and macro (national).

Within the complexity of education systems, the idea of working together to design solutions (co-creation) in TPD is often celebrated as a progressive ideal. Yet, in practice, it raises challenging questions: What does co-creation mean when power is unevenly distributed? Are all power imbalances inherently problematic? Can authority, particularly at the meso level, enable more inclusive and sustainable change? Through this blog, I shall attempt to unpack co-creation within the context of scaling TPD within South Asia (India, Pakistan and Nepal) to share a few lessons learned for policy and practice.

The British Council’s experience across India, Pakistan and Nepal suggests that the answer lies not in dismantling existing structures, but in reimagining how they work together. Co-creation, in these contexts, is less about erasing power dynamics and more about recognising, navigating and leveraging them to bridge global expertise with local realities. Organisations like ours, that have been embedded in these countries for many years and have experience of long-standing cultural and educational relationships, are uniquely positioned to play this bridging role to create mutual respect and shared purpose. We connect people, ideas and institutions across levels of the hierarchy and geographies over a long-term. Below are some examples from recent partnerships across the region.

India: Structured partnerships at scale

In India, the Competency-based Education Project, co-designed and implemented with the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) between 2020 and 2022 exemplified this partnership approach to improve assessment practices in English, science and mathematics for secondary level students. This is a carefully structured, multi-tiered partnership involving national authorities, international experts and local schools. Within this partnership, CBSE provided national leadership, while the University of Cambridge contributed through question bank development, AlphaPlus (now Assessments and Qualifications Alliance) brought in global assessment expertise, and Ecctis measured impact. CBSE Board associated schools, such as Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalaya and Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan, ensured contextual grounding.

This collaboration potentially reached 28,000 schools and embedded competency-based assessment into the national curriculum. It succeeded not because power was evenly distributed, but because it was consciously shared. The British Council’s role as a catalyst, facilitating collaboration between government, academia and practitioners, helped lift the sector collectively. The meso layer, often overlooked, became the engine of change: middle-tier officials, school leaders and teacher educators who remained in the system long after the intervention ended, sustaining its impact.

Pakistan: Balancing technology and teacher voice

In Pakistan, the English as a Subject for Teachers and Educators (EaSTE) programme in Punjab had a different focus and adopted a different model, using an online learning management system (LMS) to train 140,000 teachers in inclusive English teaching practices. The LMS was supported by a network of 3,300 Assistant Education Officers and 120 District Subject Experts. While the scale was impressive, the programme revealed the limits of technology when not fully grounded in teacher voice. Power imbalances between departments and teachers led to a top-down design. Teachers responded accordingly, taking shortcuts to complete modules without fully buying in to the additional learning burden. However, because the programme was embedded within a multi-tiered structure, it retained flexibility to adapt. Political and institutional buy-in enabled course correction, ultimately meeting its targets and improving teacher engagement. The project provided learnings in programme management for technology-based professional development. In terms of co-creating successfully, the lesson we learned was that the power imbalances are inherently part of any public system, however, their effects can be mitigated through adapting an inclusive programming approach. When managed thoughtfully, systemic inclusion can ensure reforms are scalable and sustainable and ultimately contributing to our global understanding of effective practice.

Nepal: Local ownership and its limits

In Nepal, the Quality Education Quality School (QEQS) progamme offered a grassroots model of co-creation. The British Council partnered with Kawaswoti Municipality directly to build the capacity of teachers and school leaders in English teaching and core skills. The partnership approach focussed on engaging and co-creating with head teachers, teacher educators, students, municipality officials and community members, fostering strong local ownership. The programme reached 350 teachers. Classroom observations indicated 89.29% reporting on improving their pedagogy and proficiency, 96.16% reporting on applying new skills in classrooms, and 85.53% benefiting from communities of practice.

In this partnership model, the British Council’s role was to walk alongside, providing technical expertise, facilitating dialogue and helping align local efforts with national priorities. We learned that while this grassroots partnership model enhanced contextual relevance, it also revealed the challenges of working within traditional hierarchies that resist decentralisation, emphasising the need for systemic buy-in within programme design.

Lessons for policy and practice

Across these cases, a common thread emerges: Co-creation is not a fixed formula but a dynamic process which depends on contextual factors. It requires navigating power, not avoiding it.

We have learned that teacher professional development programmes that apply a cultural relations lens are distinguished by elements of mutuality and sustainability. For cultural relations organisations like the British Council, the role is not to lead from the front, but to act as a cultural connector, bridging divides, supporting systems without overpowering them, building collective capacity and raising awareness by providing forums to discuss these uncomfortable challenges of partnership. The cultural relations approach facilitates partnerships based on mutuality and respect, which fundamentally informs an equitable co-creation approach in developing programming for teacher professional development.

We understand that applying global expertise without incorporating lived experiences and practical knowledge of those on ground, can backfire. The power to influence the direction of the programme should be equitably distributed between the beneficiaries and the programme designers for long-term sustainability of programme objectives, and we advocate for mutuality to be the core principle for co-creation within education programming. We also recognise that co-creation at the local level is powerful, but it needs support from all different parts of the education system to be truly transformative.

Lastly, our key takeaway from scaling teacher professional development in South Asia through co-creation would be a reminder that co-creation is about mutual respect, long-term commitment and shared purpose.