This post was written by Sharon Tao, Director of Level The Field. It is the second of four blogs in a series, published on Level the Field on 31 July 2025.

In Part 1 of this blog series, we discussed findings from the Third Annual G7 Global Objectives Report that examines how crises significantly impact girls’ access to education and learning. In this post, we unpack why this happens by focusing on how harmful gender norms increase the disadvantage girls experience during conflict and crisis.

The G7 Global Objectives – which aim to get 40 million more girls back into school and 20 million more reading – recognise that marginalised children, particularly girls, often face significant barriers that affect their education. Groups that are marginalised – often as a result of poverty, rurality, caste, disability or displacement, amongst others – have a very limited share of power, respect, resource and safety in their contexts and societies. However, within these marginalised groups, any privileges that remain are rarely distributed equally amongst men and women, and boys and girls. This is due to harmful gender norms that underpin unequal treatment of the genders.

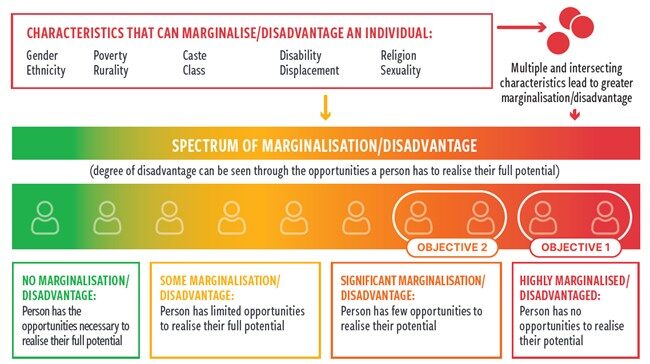

It should be noted that marginalisation lies on a spectrum. Figure 1 illustrates a number of identity characteristics that, depending on context, can contribute to how a person is treated. Generally, social norms underpin the degree to which different characteristics are valued; and if a person possesses characteristics that are not valued, the effects can entail limited levels of power, respect, resources and safety within the home, school and wider society. This type of treatment can be viewed as marginalisation, which can lead to greater disadvantage for that person and ultimately, poorer outcomes in the long-term.

Figure 1. How intersecting characteristics can lead to differing degrees of marginalisation

To the left of the spectrum is a person with characteristics that do not lead to any form of marginalisation – which can be viewed as advantage or privilege – in that they have the opportunities and enabling factors to realise their full potential. At the other end of the spectrum is a person with multiple and intersecting characteristics that may not be valued within their context and can thus lead to compounded disadvantage, which limits their ability to realise their full potential. In between lies the majority of people who experience some form of disadvantage, but to differing degrees.

As noted in figure 1, the Global Objectives implicitly have a focus on girls at the right end of the spectrum. The aim of Global Objective One is to get 40 million girls who would otherwise be out of school, back into school. These are highly marginalised girls who have already been pushed or pulled out for a variety of reasons, including conflict or crisis. Global Objective Two aims to ensure 20 million more girls are reading proficiently. These are girls who are still in school but who tend to be from the poorest and/or most rural groups. These girls also tend to do worse than boys from the same marginalised groups due to the unequal gender norms that disadvantage them further.

It should also be noted that in crisis contexts, children who were most marginalised prior to the crisis will likely suffer the greatest disadvantage during and after the crisis as well. Within a crisis-affected context – be it a village affected by conflict or flooding, or a camp for internally displaced populations – those most privileged will likely have the power, resources and social capital to find safety first. The most disadvantaged are at the other end of the spectrum with no safety nets. Within these marginalised groups, a double disadvantage occurs when harmful gender norms put girls at an even greater disadvantage than boys. For example, in crisis contexts, heightened gender norms perpetuate labour markets and public spaces that exclude women and girls. This leads to excessive pressure on boys to support poverty-stricken families. However, girls from similarly poverty-stricken families can be equally pressured to contribute income, but options are often limited to sex work or forced marriage so that families can access a dowry or food rations.

There are many examples of how harmful gender norms affect girls and boys differently during crises and figure 2 provides an abridged version of what is presented in the Global Objectives Report. These examples are framed within three types of child protection issues that are pronounced during crises, and these categories are aligned with the marginalisation spectrum to demonstrate that the most disadvantaged girls and boys are likely to experience these issues most frequently.

Figure 2. How crisis affects girls and boys from the most disadvantaged end of the spectrum

This overview of crisis effects is extensive but not exhaustive – there are many additional ways in which the intersecting characteristics of disability, sexuality and ethnicity (particularly if violence is along ethnic lines) can further compound disadvantage for girls and boys. For example, girls with disabilities face a triple disadvantage as a result of their displacement, disability and gender, as they are seen as ‘easy targets’ for sexual violence and cannot access humanitarian aid due to attitudinal and physical barriers. Understanding the effects of crisis on the most vulnerable children, such as girls with disabilities, is important because they are often the most invisible and thus left furthest behind.

That said, the comparison in figure 2 is not meant to represent a competition of disadvantage between girls and boys. However, in order to better illustrate how gender inequalities operate, comparing the very different lived experiences of girls and boys during crises is helpful. It should also be noted that this comparison is for girls and boys with the same background characteristics (i.e., those at the same point on the marginalisation spectrum), because comparing lived experiences from the same family or group makes it easier to see the additional disadvantage that gender norms impose.

In general, the hidden effects of gender inequality during crises can be most clearly seen through the differing degrees to which girls and boys are afforded power, respect, resource and safety. Many of the challenges for girls, particularly those related to sexual violence, are a result of unequal gender norms that afford girls very little respect or safety. Suffice it to say, these effects significantly impact progress towards the Global Objectives of getting more girls into school and learning, and this is discussed further in the Third Annual G7 Global Objectives Report.

Overall, this blog has aimed to summarise some of the key themes and concepts discussed in the Report, and will hopefully stimulate discussion, reflection and refocused attention to achieving both the Global Objectives and gender equality, particularly in crisis contexts. As the blog and report demonstrate, there is still a lot of work to be done.