This blog was written by Dr Anudeep Lehal, education and development specialist with Humana People to People India.

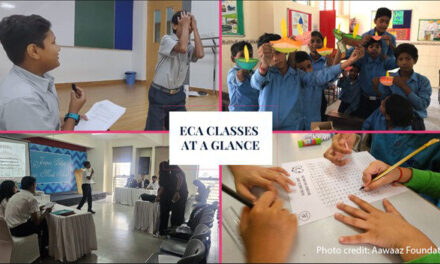

When I first stepped into the classroom that morning, the noise caught me by surprise. Dozens of children were talking at once — not in chaos, but in conversation. Groups of three huddled over shared notebooks, whispering, debating, laughing, and scribbling answers on the blackboard. Despite the worn desks and faded walls, the energy in that room was unmistakable. These children were not just learning; they were learning together.

I was there to observe a peer learning model that has been quietly reshaping how we think about teaching and learning — the TRIO approach.

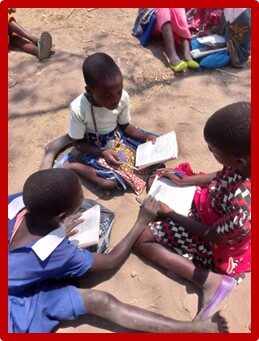

A TRIO brings together three learners from the same class, each with different strengths, who live near one another. They work as a team — at school, at home and often on the walk to and from school. They study, support and motivate one another to stay in school and keep progressing. The idea is beautifully simple: when learning becomes a shared responsibility, every child has a reason to show up, to try again and to succeed.

For teachers, TRIOs have become a lifeline in overcrowded classrooms. In schools, where one teacher may face 70 or more students, TRIOs help make learning personal again. Instead of lecturing to a sea of faces, teachers move between groups, guiding and encouraging as children take charge of their own progress. Over time, we have seen something shift — both in the learners, as well as in the teachers. Teaching becomes less about control, and more about trust — and thoughtful guidance.

In India, schools applying the TRIO system have reported encouraging improvements — higher attendance, fewer grade repetitions and better academic performance. Parents also describe their children as more confident, curious and engaged. That confidence ripples outward — to families, to communities and to the idea of education itself.

These gains matter, as India continues to face significant learning challenges, with only 50% of Grade 5 students able to read a basic Grade 2 text. In this context, peer learning models like TRIOs are helping teachers address diverse learning levels within the same classroom — a challenge that affects millions of children across the country.

Thousands of kilometres away in Malawi, the situation is strikingly similar. According to UNICEF, only 19% of children aged 7 to 14 in Malawi have foundational reading skills, and just 13% have foundational numeracy skills. Large class sizes — which are on average 65, but can reach 80 or higher pupils per teacher in rural areas — make it difficult for educators to provide individual support. Yet here too, teachers are finding hope in TRIOs.

Later this year, a delegation from Malawi’s Ministry of Education will visit India, supported by the European Union through ENABEL under the Regional Teachers’ Initiative for Africa (RTIA). Together with colleagues from Humana People to People India and Development Aid from People to People (DAPP) Malawi, they will spend time in schools where TRIOs have taken root — observing lessons, talking with teachers and learning from the experiences of Indian educators who have been refining the model for years.

The exchange is part of the project “Upscaling Child-Centred Teaching and Learning Innovation in Dowa District (2025–2027)”, implemented by DAPP Malawi in partnership with the Ministry of Education. The project is piloting the TRIO model in 40 schools, reaching nearly 19,000 learners. Over the next two years, this will expand to 240 schools, involving 800 teachers and 75,000 children. The hope is that the success seen in India will be mirrored in Malawi, creating further evidence of a simple, low-cost and effective model that can be used in rural classrooms around the world.

This collaboration between India and Malawi represents something larger than two countries exchanging ideas. It is a reminder that the future of education depends not only on innovation, but on solidarity — the willingness to learn from one another, to adapt and to build systems that can endure.

The TRIO model does not rely on expensive technology or external expertise. It thrives on relationships: between students, between teachers and communities, and between countries that choose to learn side by side. It shows that transformation can begin with something as small as three children helping each other read, write and dream.

As the world works toward ending learning poverty and strengthening education systems, we need approaches that are not only effective but resilient — rooted in trust, collaboration and local ownership. That is where change becomes lasting — when learning connects people, and education becomes a shared endeavour of trust, collaboration and guidance.

Great initiative and best. Wishes

A wonderful approach as we have found in the CHILD TO CHILD model in early childhoid education. Children often learn more from their peers than their teachers. Do you have any documentation?