This blog was written by Mesele Araya, IGC Country Economist, Policy Studies Institute, Ethiopia. For the 2025 UKFIET conference, a record 37 individuals from 15 countries, including Mesele, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their research or experience of attending the conference.

Introduction

Over the past 15 years, Ethiopia has embarked on one of the most ambitious education reforms in Sub-Saharan Africa through the General Education Quality Improvement Programme (GEQIP). Implemented in three phases since 2008, GEQIP has sought to improve both the quality and equity of schooling. The most recent phase, GEQIP-E (2018–2022), placed equity at its core, with targeted support for girls, children with special educational needs, and those living in the country’s Emerging Regions (ERs) such as Somali and Benishangul Gumuz. These regions, often more remote from the centre of the country and underserved, have historically lagged behind the Core Regions (CRs)—including Addis Ababa, Oromia, Amhara, Tigray and SNNP—in terms of enrolment, resources and learning outcomes. This blog draws on school facilities, teacher professional development and pupil assessment data from 2018/19 and 2021/22, to examine whether GEQIP-E has helped reduce these disparities, particularly in education inputs, early numeracy and learning progress.

Progress in education inputs

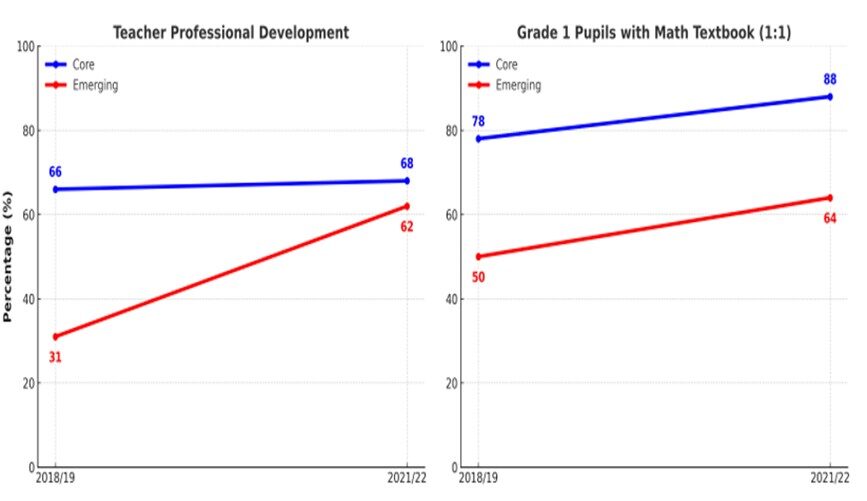

Schools in Ethiopia’s ERs achieved significant progress in reducing inequities in school inputs during the GEQIP-E reform period. For example, in 2018/19, only 31% of schools in ERs engaged teachers in school-based professional development, compared with 66% in CRs. By 2021/22, this gap had nearly closed, with ERs reaching 62% and CRs 68% (Figure 1, left). Similarly, textbook access also improved during the period. In 2018/19, just 50% of Grade 1 pupils in ERs had a one-to-one math textbook compared to 78% in CRs. By 2021/22, availability had risen to 64% in ERs and 88% in CRs (Figure 1, right). However, more than a third of ER pupils still lacked textbooks, compared to only 12% in CRs by 2021/22. These results show that GEQIP-E was particularly effective in strengthening teacher capacity in disadvantaged regions, while persistent challenges remain in ensuring equal access to learning resources.

Figure 1. Slope graphs showing convergence between core and emerging regions in teacher professional development and textbook access between 2018/19 and 2021/22

Shifting learning gaps: Grade 1

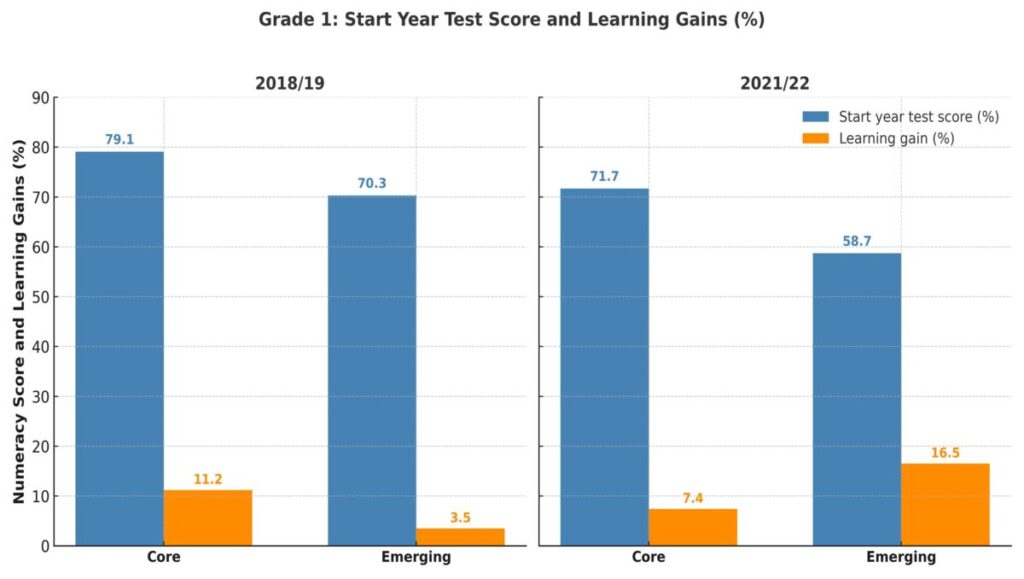

Assessment data from Grade 1 highlights both the persistent disadvantage faced by pupils in ERs at the start of schooling and the progress made once they are enrolled. In 2018/19, Grade 1 pupils in ERs entered school with lower average numeracy scores (70%) compared to their peers in CRs (79%). During the school year, this gap widened further, as ER pupils gained only 3.5%, while CR pupils gained 11.2%. This means that children in ERs faced a “double disadvantage”: starting behind and progressing more slowly (Figure 2, left). By 2021/22, however, the picture had changed. While the entry gap remained (59% vs. 72%), pupils in ERs made much greater yearly learning progress than their CR peers (16.5% vs. 7.4%) (Figure 2, right). The difference is statistically significant at 1%. This meant that pupils in ERs not only caught up in terms of progress but actually outperformed CRs in value-added learning by more than 9 percentage points.

Figure 2. Grade 1 numeracy scores at the start of the school year and value-added learning (%), 2018/19 and 2021/22

Shifting Learning Gaps: Grade 4

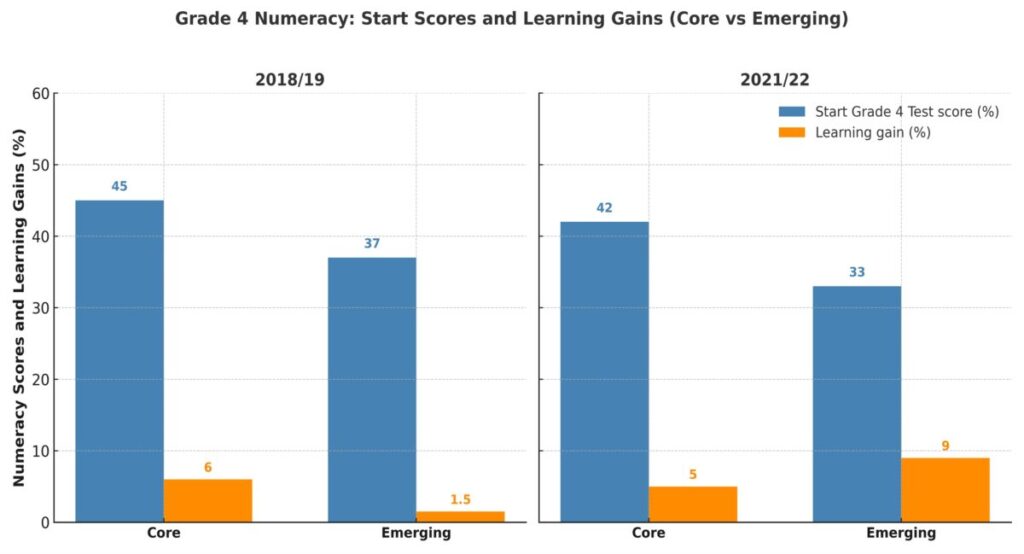

A similar story emerges in Grade 4 as indicated in Figure 3. In 2018/19, pupils in ERs again started behind, with average numeracy scores of 37%, compared to 45% in CRs. They also gained less during the year (1.5% vs. 6%), meaning the gap widened as they advanced through primary school (Figure 3, left). By 2021/22, ER pupils still entered Grade 4 behind their peers (33% vs. 42%), but they made greater yearly gains—adding 9% compared to 5% in CRs (Figure 3, right). This difference is also statistically significant at 5%. This represents a clear reversal from the earlier trend, with ER pupils catching up rather than falling further behind.

Figure 3. Grade 4 numeracy scores at the start of the school year and value-added learning (%), 2018/19 and 2021/22 for emerging and core regions

Together, the Grade 1 and Grade 4 results highlight a consistent pattern: although children in ERs continue to start school at lower levels, by the end of the GEQIP-E programmed they made stronger progress once enrolled.

Why does this matter?

The evidence points to a significant shift in Ethiopia’s education landscape. In the past, children in ERs were disadvantaged twice over—starting behind and learning less over the school year. By the end of the GEQIP-E programme, while starting gaps remain, they are at least closing the gap in progress. This has important policy implications:

- Equity-focused reforms can deliver results. The GEQIP-E focus on professional development, targeted resources and equity appears to have paid off, enabling disadvantaged regions to accelerate learning.

- Early years remain critical. Persistent entry gaps show the need for stronger investment in early childhood education and school readiness programmes, particularly in ERs.

- Resource equity must be sustained. Textbook availability and other learning resources remain unevenly distributed. Unless these gaps are closed, emerging regions will struggle to sustain their progress.

Lessons for Ethiopia and beyond

Ethiopia’s experience under GEQIP-E offers lessons not only for national policy but also for the wider global debate on equity and learning. First, it shows that even in contexts where starting inequalities are stark, well-designed, equity-focused reforms can accelerate progress among disadvantaged groups. Second, it highlights the importance of combining system-level inputs (teacher training, textbooks) with measures that directly support learning. For policymakers and development partners, the message is clear: it is not enough to expand access to education. Reforms must also focus on who is learning, how much, and under what conditions, with special attention to the most disadvantaged.

Conclusion

Despite challenges—including the COVID-19 pandemic—GEQIP-E has contributed to important progress in narrowing learning inequalities between Ethiopia’s core and emerging regions. Pupils who once faced a “double disadvantage” are now making faster learning gains once they are in school. To sustain this momentum, greater investment is needed in early years and foundational interventions, ensuring that children in ERs start school on a more equal footing. At the same time, equity-focused reforms, such as those pioneered under GEQIP-E, should remain central to Ethiopia’s education strategy. The lesson is that with the right policies and sustained commitment, it is possible to close entrenched gaps in learning and create a fairer education system for all children.