This blog was written by Dr Eucharia Chinwe Igbafe, University of South Africa. Eucharia will be presenting at the UKFIET 2025 conference in a session entitled: ‘Skills and knowledge for sustainable futures: Leveraging AI to empower low-literate busy parents and entrepreneurs to complete children’s homework’.

Introduction

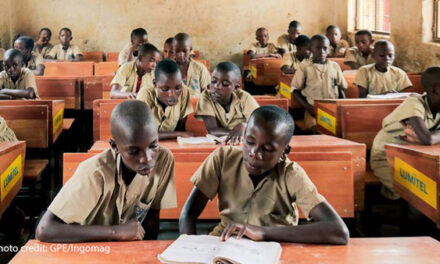

When the classroom starts at home, we talk about sustainable education. We often picture schools: teachers, textbooks, digital tools, and carefully crafted curricula. Yet for millions of children around the world, the real learning journey begins at home, with parents who may not have finished school, may not read confidently, and are often juggling multiple jobs. In places like Nigeria, low literacy among parents, particularly entrepreneurs in the informal sector, creates hidden but profound challenges. When a child brings homework to the house, although this could be a great way to build connection between them and their parents, it can also result in feelings of shame for the parents.

One mother said: “The children will ask me, ‘Mummy, help me.’ But I never finished school. I feel like a failure all over again.”

But here is the truth: these parents care deeply. What they lack is not love or motivation, it is support that understands their reality. Therefore, the thoughtful use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) can offer that support, transforming homework time into a moment of bonding, confidence, and learning for the whole family.

The five barriers low-literate parents face

Research shows parental engagement is one of the most powerful predictors of a child’s academic success. But for low-literate or time-constrained parents, engagement is easier said than done. There are five key barriers low-literate parents face that stands out:

- Difficulty understanding school communications: Most school updates are text-based, making them inaccessible for many parents.

- Time poverty: Between work, caregiving and running businesses, many parents have little time for school involvement.

- Low confidence in helping with homework, especially when materials are complex or full of academic jargon.

- Lack of accessible resources: Few tools are designed for non-literate users.

- Minimal early literacy practices at home: This impacts children’s long-term language development.

These challenges are not just logistical, they are emotional. Many parents experience shame, guilt and a deep fear of being “found out” as incompetent by their children.

From avoidance to empowerment: A community-centered AI intervention

To bridge this gap, I partnered with a non-governmental organisation (NGO) and community leaders across Bayelsa state in Nigeria. This organisation and community leaders were keen in identifying and training the low-literate and busy parents in Artificial Intelligence, specifically (Meta AI) a voice-first assistant that parents could use to:

- Listen to homework instructions read aloud

- Translate materials into their local language

- Ask questions without typing

- Scan homework pages and receive step-by-step explanations

There were no keyboards. No need to write or spell. Parents could speak in their own language and receive clear, verbal feedback from just their mobile phones. One father shared:

“Now I don’t pretend to be busy when they ask. We ask the app and learn together.”

The pilot programme ran over six weeks in local community centres and schools. Parents, particularly mothers, joined voluntarily driven by a desire to help their children succeed.

Learning at the dinner table: Early outcomes and transformations

What started as an experiment in digital inclusion turned into something much more personal. The AI did not just answer questions; it opened the door to learning as a family. Parents reported:

- Increased confidence in engaging with schoolwork

- Reduced anxiety and guilt around homework time

- Stronger emotional bonds with their children

- New digital literacy skills that sparked curiosity beyond homework

One mother said: “I always thought I wasn’t smart enough. Now we sit and do the homework together. My children even teach me how to use the app.”

Lessons Learned

Facilitate with, not for, parents

Parents were involved from day one, not just as users, but as co-facilitators. They were trained, tested, gave feedback and shaped the training tone and language. AI has been proven effective in education and training of adult educators.

Voice matters more than visuals

In low-literate households, a calm, supportive voice interface helped reduce fear and build trust. The app became a safe, judgment-free space.

Homework became a time of healing

Parents and children reported more quality time. Many created new routines around homework, 10 minutes after dinner, 15 before bed. AI does not replace school, it extends it, and this was not about bypassing teachers, but supporting families in ways the system often overlooks.

Implications for policy and practice

To build educational systems that truly include every child and every parent and caregiver, we must act on these insights:

- Include parents in digital education strategies

Family literacy training should be part of national educational technology plans, not an afterthought.

- Design for empathy and accessibility

The use of technology must be normalised even in local languages; simplicity and dignity should guide every design decision.

- Measure soft outcomes too

Beyond test scores, track indicators like parent confidence, child motivation and family bonding.

- Elevate parent voices

Bring parents into education discussions, whether in local Parents Teacher Association meetings or national policy forums.

Linking to global goals

This initiative directly supports SDG4 (Quality education, by enabling home-based learning support) and SDG10 (Reduced inequalities by empowering parents in low-literacy communities). It also reflects the 2025 UKFIET Conference theme of ‘Skills and Knowledge for Sustainable Futures’ by showing that skills development can (and should) start at home, with parents as partners.

Where do we go from here?

The potential for scaling is vast:

- In refugee settings, where language barriers isolate families

- In rural areas, where teacher support at home is limited

- In urban centres, where long work hours cut into family time

But scaling must be thoughtful. It must centre on co-facilitation, trust-building and human-first technology. There is a need to refine the training model, explore partnerships to provide affordable devices, and expanding our reach. If you are working on similar efforts, we invite collaboration.

Conclusion

Education starts with who we include. Sustainable education is not just about what happens in classrooms but who gets to be part of the learning journey. If we facilitate with empathy, starting from the lived realities of those often left out, we can create systems that work better for everyone. When a parent who once avoided homework now proudly says, “We do it together”, we are not just closing the homework gap. We are rewriting the narrative of what it means to be an engaged parent. That is not just an outcome. That is a transformation.

This article by Dr Eucharia is educative and insightful. It has the potential to impact positively on the education sector if implemented by policy makers. It is empowering to the low income parents who are faced with challenging task of helping children with their school work and providing food for them at the same time.

A very important piece of work from Dr Igbafe.

Excellent! This deserves widespread publicity and practical support. Share it at the forthcoming UKFIET Conference…