This blog was written by Abdul-Razak Inusah (PhD) Senior Lecturer in Linguistics and Education, University for Development Studies, Ghana. For the 2025 UKFIET conference, a record 37 individuals from 15 countries, including Abdul-Razak Inusah, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their research or experience of attending the conference.

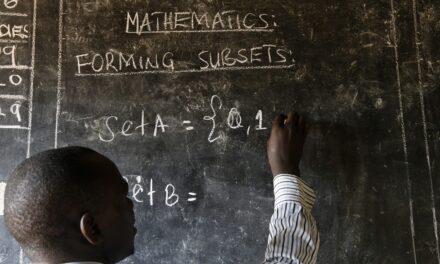

Multilingualism is a defining feature of Ghana’s sociolinguistic landscape, with over 83 languages spoken by 75 ethnic groups across the country. Despite this rich linguistic diversity, the educational system continues to struggle with implementing effective multilingual education policies to adequately support multilingual learners. The current Language Policy in Education recommends the use of Ghanaian languages as a medium of instruction in the early years (Kindergarden to Primary 3), yet its uptake has been limited due to frequent policy shifts, lack of teacher training, and widespread disillusionment. This disconnect between policy and practice is not unique to Ghana, but reflects a broader challenge for educators across sub-Saharan Africa.

While there is a growing body of literature on multilingual education in Africa, much of it focuses on policy-level analysis or theoretical advocacy for mother-tongue/L1-based instruction. There remains a significant gap in empirical research that investigates how multilingual pedagogical approaches are understood, adapted and enacted by teachers in real classroom settings particularly in linguistically diverse environments.

At the University for Development Studies in Tamale, Ghana, we have taken steps to address this gap by introducing teacher training which focuses on introducing primary school teachers to the principles of multilingual education and supporting them to apply these to learning and teaching material development. This initiative draws on the teacher training toolkit originally developed for The Gambia—Multilingual resources for primary schools in The Gambia. We adapted the latter for use in Ghana and piloted it with in-service and pre-service teachers in the 2024/2025 academic year. In addition, we also used the toolkit with over 250 early childhood development (ECD) teacher trainees. This mixed cohort allowed for comparative insights across early years and primary education settings, both of which are critical for foundational language development. The structured, research-led evaluation of the toolkit’s effectiveness and adaptability in Ghana contributes insights into the gap between policy and practice in multilingual education in Africa.

The pre-service teachers implemented the training in their classrooms during teaching practices where they taught various subjects based on the Standards-Based Curriculum which focuses on core skills and 21st-century competencies through the teaching of all subjects at primary levels, namely: English, mathematics, science, creative arts, social studies and ICT (Information and Communication Technology) in five selected schools in Tamale.

In conclusion, this gap is addressed by looking at the impact of teacher training on multilingual education on pre-service and in-service primary school teachers and how the new experiences and outcomes of implementing the multilingual education training enhances multilingual education in Ghana. The new concepts introduced allow pre-service and in-service teachers to reflect on their practice differently and change their teaching practice, for example by introducing multilingual storytelling and labelling in the languages of the learners.

I can’t wait for it implementation in Ghana