This blog was written by Maria Maalouf, Centre for Lebanese Studies. For the 2025 UKFIET conference, a record 37 individuals from 15 countries, including Maria, were provided with bursaries to assist them to participate and present at the conference. The researchers were asked to write a short piece about their research or experience of attending the conference.

“What does it really mean to ‘return to school’ after war? In Lebanon, being physically back in a classroom does not guarantee inclusion, safety or learning. The deeper barriers, such as poverty, displacement, and systemic inequality, remain untouched.”

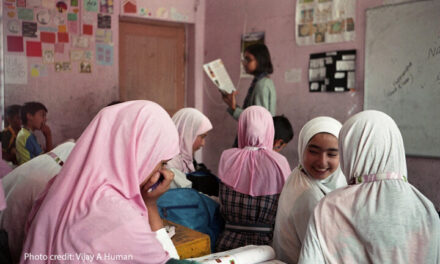

After a conflict or crisis, the primary goal for education is usually to get children back into the classroom. But is showing up at school enough? Research presented at the UKFIET 2025 session, ‘Teaching and learning in refugee contexts,’ suggests the answer is No. Across studies from Colombia, Uganda, Lebanon, Bangladesh and Algeria, the message was clear: Real inclusion goes far beyond physical return.

Today, nearly half of the world’s displaced people are children. For them, learning is not only about catching up on lessons, but also about feeling safe, recognised and supported in systems often stretched to breaking point.

What emerged from the session presentations

In her presentation, “Beyond the curriculum: The multifaceted learning experiences of Venezuelan immigrant and refugee students in Colombian schools,” Marcela Ortiz showed that integration is about much more than enrolment or language learning. Research with 10th-grade students in two schools in metropolitan Cúcuta, Colombia, during the 2023 and 2024 academic years highlights how abrupt curricular shifts, unfamiliar teaching practices, and new social dynamics unsettle prior knowledge and identities. Yet, students also demonstrate remarkable resilience, reconstructing their learning pathways and adapting to new contexts. What emerges from the study’s findings is a picture of learning as both academic and deeply social. School integration policies must therefore go beyond “access” to recognise prior experiences, value cultural knowledge, and respond to the emotional labour of adaptation. In this sense, inclusion means supporting not just achievement, but the rebuilding of students’ identities and sense of belonging.

As for the Ugandan humanitarian contexts, as shown by Sandrine Bohan-Jacquot, in her presentation titled “Counted, seen and included: disability data in schools in humanitarian settings”, children with disabilities are often invisible in official systems. Research in a Ugandan refugee settlement evaluated the Child Functioning Module – Teacher Version (CFM-TV), a straightforward tool that enables teachers to identify functional difficulties in learners. The findings are striking: not only did the tool generate reliable data for planning, but the process itself shifted teachers’ perceptions, fostering more inclusive attitudes and practices in classrooms. This suggests that inclusion begins with recognition. When learners are counted and seen, their participation improves. More importantly, the act of data collection becomes a pedagogical intervention in itself, prompting teachers to view diversity as part of everyday teaching rather than an exception to it.

Moving to Algeria and Bangladesh, Dr Sarra Boukhari from Swansea University presented Children’s experiences of co-existence amongst refugee populations in Bangladesh and Algeria: Implications for fostering intercultural dialogue and inclusive educational policy and practice. She said that too often, refugee education research overlooks how host community children experience displacement in their midst. The comparative study employed arts-based methods with 120 children to explore how co-existence with refugees is understood across different age groups. The results show that young children (aged 5–7) emphasised play and everyday acts of inclusion, while adolescents (aged 11–15) linked coexistence to strained resources, government responsibility, and social tensions. The findings remind us that inclusion is not only about refugees but also about how host communities navigate diversity. Listening to children’s own interpretations reveals empathy, resilience and at times frustration — all of which must inform policies that promote intercultural dialogue and inclusive classroom climates.

Finally, in my contribution to the panel, titled “An intersectional lens on the experience of returning to school after war in Lebanon”, I concentrated on Lebanon’s education system. Fragile long before the most recent Israeli war, it has long been marked by deep inequalities rooted in class, sectarian governance, nationality, gender and disability. The compounded crises of financial collapse, COVID-19 and displacement have widened these gaps, leaving public schools overstretched and under-resourced. Using intersectionality, research has shown that exclusion occurs through the overlapping factors of socio-economic status, gender, legal status, disability and displacement history, rather than just one at a time. The study drew on interviews with Lebanese and Syrian parents and teachers affected by the war (2023–2024) to capture how these intersecting disadvantages shape children’s everyday schooling experiences, strategies and outcomes. The study called for a shift towards what it terms a Critical Inclusion theory: focusing on how systems themselves produce exclusion. This means viewing inclusion not just as physical presence, but as the system’s ability to dismantle emotional, social and structural barriers. Lebanon presents a critical site for rethinking what “inclusive education” means in crisis contexts.

Why inclusion still falls short

Across the different papers in this panel, common challenges emerged that help explain why inclusive education so often remains out of reach, even when access is guaranteed. One recurring theme was the visibility gap. Learners most at risk, like children with disabilities, displaced populations, and those facing overlapping exclusions, are too often missing in data, or misrepresented. Without being counted properly, they remain invisible to policy and support.

Another challenge was the persistence of a one-size-fits-all approach. Post-crisis “back to school” campaigns tend to focus narrowly on enrolment, treating physical return as the end goal. But being present in a classroom does not mean being included, especially when learning loss, trauma and disrupted schooling are left unaddressed.

The presentations also underlined the gap between policy and practice. While official frameworks consistently affirm commitments to inclusion, families and teachers described realities shaped by trauma, poverty and instability. Emergency responses often fail to account for these lived experiences, thereby widening the gap between policy language and what actually occurs in classrooms.

Finally, teacher capacity remains a critical barrier. Teachers are on the frontlines of inclusion, yet without time, training and resources, they cannot realistically turn commitments and data into inclusive practices. This disconnect leaves them overburdened and students underserved.

Lessons for policy and practice

The presentations didn’t just point to problems; they also shared valuable lessons about what it takes to make education genuinely inclusive.

The first message was clear: going back is not enough. Learners need schools that recognise their prior knowledge, identities and emotional needs. Enrolment alone cannot deliver inclusion. Systems must embed psychosocial support, flexible learning pathways, and recognition of prior learning so that displaced and marginalised children can not only attend school but also participate and thrive.

Another lesson was the importance of local voices and knowledge. Children, families, communities and teachers hold essential insights into both barriers and solutions. For reforms to be inclusive, they need to start with these perspectives instead of being imposed from above.

The panel also reminded us that exclusion is layered. Children are rarely excluded for one reason alone. Socio-economic status, gender, disability, legal status and displacement intersect in ways that single-category interventions cannot address. More holistic strategies are needed, ones that tackle overlapping disadvantages and recognise the full complexity of learners’ lives.

Moving forward

Getting children back into classrooms after conflict is a vital first step, but it cannot be the last. True inclusion means going further: valuing learners’ experiences and putting them at the centre of designing and building resilient systems that recognise overlapping disadvantages. In addition to creating classrooms where children feel they belong and are safe.

As UNESCO reminds us, Sustainable Development Goal 4 is about inclusive and equitable quality education for all. The research shared at UKFIET shows that to reach this goal, we must continue to ask difficult questions: Who is being left out? Who is invisible in the data? And what does it take for children not only to return, but to truly learn and thrive?