This blog was written by Zain Ul Abidin, GLOBED Scholar and Data Analyst (Equality, Diversity and Inclusion) at Research and Innovation Services, University of Glasgow.

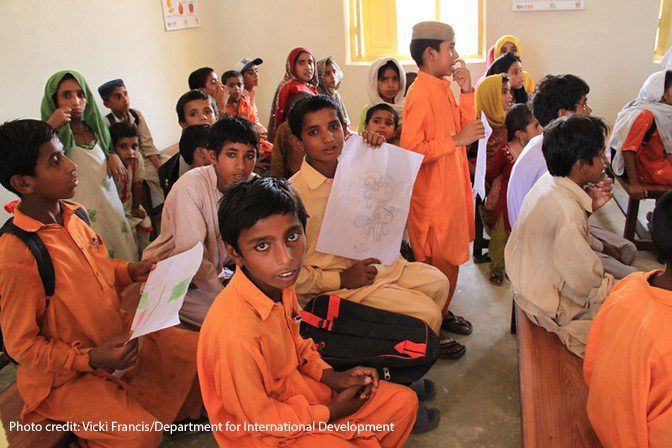

Education remains the cornerstone of our collective journey towards economic prosperity, social equality, and global citizenship. Yet, despite commendable strides in recent decades, we are still grappling with a formidable challenge: ensuring equitable access to quality education for all, irrespective of one’s socio-economic status. One innovative approach that has been gaining traction worldwide is the use of education public-private partnerships (ePPPs). These partnerships sit at the unique intersection of public interest and private sector efficiencies and aim to provide quality education to all. But one question looms large: do ePPPs successfully facilitate equity in education? To explore this question, we delve into the educational landscapes of Chile and Pakistan, two nations that have boldly embraced ePPPs.

The success of ePPPs hinges largely on how they are regulated. Comprehensive regulatory frameworks play a pivotal role in ensuring that these partnerships work towards the collective goal of educational equity. Without meticulous regulation, the noble intention of ePPPs can easily deviate, potentially exacerbating the very inequities they aim to address. Regulation in this context includes defining who can operate schools, how they are funded, and how parents and students can choose among them – the very elements that shape the ecosystem within which these partnerships function.

Drawing on the comprehensive framework developed for the background paper of the Global Education Monitoring Report by UNESCO focusing on the governance of non-state actors in education, this blog will analyse the interplay between the regulatory mechanisms of accountability, funding, school choice, and workforce and their implications for equity. Through the lens of two countries, Chile and Pakistan, with markedly distinct experiences with ePPPs, we will navigate the terrain of education policy, governance, and practice to understand the successes, challenges, and lessons gleaned from their respective journeys.

Unraveling the complexities of autonomy and accountability

ePPPs present a compelling proposition. They propose to combine the innovation and efficiency of the private sector with the social responsibility and scale of the public sector to deliver quality education for all. At the heart of this partnership model is the concept of autonomy – the freedom for private entities to make crucial decisions regarding school organisation, budget allocation, teacher policies, and pedagogical orientation. On paper, this approach offers a radical shift in education governance, promoting efficiency and innovation in service delivery. But does it work for all stakeholders?

To balance this autonomy and safeguard public interests, ePPPs are designed with robust accountability mechanisms. These mechanisms ensure that all publicly funded schools, including those privately managed, adhere to the government’s quality standards and equity goals. The intention is to ensure that every student, irrespective of their background, receives a high-quality education. In this context, it’s worth examining the experience of Chile and Pakistan, two countries that have championed ePPPs in their respective educational landscapes.

Chile’s ePPPs are steered by the Preferential School Subsidy Law (PSS Law), a policy designed to enhance access to non-state subsidised schools for marginalised students. The PSS Law, with its rigorous accountability framework, aims to improve learning outcomes across the board. However, the law’s focus on performance-based measures has led to unexpected consequences. Some underperforming schools, in an effort to sidestep these measures, have resorted to strategic behaviour, including tactics that could potentially compromise the quality of education provided. This avoidance mechanism not only undermines the essence of the PSS Law but also poses a significant challenge to achieving true educational equity.

Pakistan presents a different scenario. The country has adopted stringent monitoring of its ePPPs through programmes such as the Education Voucher Scheme (EVS), Education Management Organization (EMO), and Foundation Assisted Schools (FAS). These programmes, managed by the Education Foundations, focus on strict compliance with government regulations and policies. However, the over-reliance on quality assurance tests as the primary evaluation tool has led to the marginalisation of underperforming schools. This ‘sink or swim’ approach denies struggling schools the support they need to improve, ultimately impeding the overarching goal of educational equity.

Moreover, both countries face criticism over the quality of instruction, curriculum, and pedagogical practices in ePPPs. In Pakistan, school administrators and teachers have raised concerns about the emphasis on rote memorisation and the lack of creativity and innovation in teaching methods. These concerns indicate a need for more investment in teacher training, better learning materials, and improved physical infrastructure. In Chile, despite being renowned for its robust PPP framework, the gap in learning outcomes between privately managed and publicly managed schools persists. It’s a glaring reminder that increased private sector involvement is not a guaranteed solution for systemic education challenges.

The narratives from Chile and Pakistan highlight the importance of carefully balancing autonomy and accountability within ePPPs. Both countries offer a lesson in the complexities of implementing robust accountability frameworks, crucial for upholding educational equity and quality. The dance between autonomy and accountability is delicate and intricate, one where missteps could have significant consequences on the journey to educational equity.

Funding: Equity or inequity?

Funding regulation represents a crucial area of focus in ePPPs, with its management significantly influencing the quality and equity of education. Chile has adopted an egalitarian approach in this regard. The country has phased out tuition fees for private subsidised schools by introducing the ‘gratuity grant.’ This measure, along with the allocation of additional funding for socially disadvantaged students, aims to make quality education accessible to all segments of society.

On the other hand, Pakistan’s approach to ePPP funding is considerably varied, depending on the specific programme. While these mechanisms have seen some successes, they’ve also been criticised for potentially exacerbating existing inequalities. Critics argue that the funding processes often lack transparency and disproportionately favor urban areas, thus creating imbalances in the accessibility of quality education.

School choice and admissions: A natter of rights and accessibility

ePPPs aim to convert education from a circumstantial necessity into a matter of choice. The goal is to prevent segregation and ensure equitable access to quality education for all students, regardless of their socio-economic background. Chile’s School Admission System (SAE) and Pakistan’s EVS are significant strides towards this end.

The SAE provides a universal and centralised method for school choice, increasing access to better schools for disadvantaged students. Yet, its impact on school segregation remains a matter of debate. On the other hand, Pakistan’s EVS empowers parents to choose schools for their children. While it has managed to uplift school participation rates and improve academic outcomes, the EVS has yet to make a significant dent in educational inequality. Children from underprivileged backgrounds continue to face substantial barriers to access.

Teacher quality: The workforce conundrum

An effective education system depends heavily on the quality of its teachers. In ePPPs, the autonomy to manage human resources can, in theory, enhance educational quality by incentivising high-performing teachers. However, striking the right balance between autonomy, cost efficiency, and quality assurance is a critical challenge. If not managed carefully, PPPs could inadvertently compromise on teacher quality by hiring less experienced or underqualified teachers to reduce costs. This can not only diminish the quality of education but also exacerbate educational inequity.

Let’s revisit Chile and Pakistan’s experiences with managing the teacher workforce within ePPPs. Chile has embarked on an ambitious effort to standardise the career progression for teachers across state and non-state subsidised schools through the New System of Teacher Professional Statute (STPD). This law aims to ensure equal professional development opportunities for all teachers and foster an environment of equitable access to quality education. However, the transition to this new system is phased, leading to a duality of contractual regimes that persist and potentially affect teaching quality and, consequently, student learning outcomes.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, the government has mandated a minimum educational qualification and training requirement for teachers within ePPPs. Despite this positive step, there are concerns about the quality of the training and curriculum in these diploma programmes, often leading to the continued use of traditional and ineffective pedagogical methods. This has resulted in criticism of ePPPs for insufficient in-service training and inadequate human resource development. These issues underscore the importance of robust teacher training and professional development in achieving educational equity.

The intricacies of regulatory policies and educational equity

The quest for equity in ePPPs, as evidenced by the experiences of Chile and Pakistan, is a complex endeavour. Both countries have adopted diverse policy measures to enhance educational equity. Chile’s focus on provider diversity and stringent regulation in the authorisation of providers contrasts with Pakistan’s emphasis on technical capacity and financial viability, but lacks robust regulatory measures. While these approaches are reflective of each country’s unique context, they also highlight the trade-offs in policy design and implementation.

Funding mechanisms, an essential component of ePPPs, also show marked differences. Chile is phasing out tuition fees and implementing compensatory funding mechanisms, while Pakistan employs various funding models across different ePPPs programmes. While both nations strive for educational equity, the outcomes of these efforts have been mixed, with limited impact on the equitable distribution of disadvantaged students in schools.

Conclusion: The road ahead for achieving equity in ePPPs

The juxtaposition of Chile and Pakistan’s experiences paints a vivid picture of the complexities involved in leveraging ePPPs to achieve educational equity. The nuanced interplay between autonomy, accountability, and regulatory policies underscores that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to tackling educational equity in ePPPs. Each country’s unique context and educational priorities must guide the design and implementation of regulatory policies.

As we strive for educational equity globally, it is crucial to understand and learn from these diverse experiences. Moving forward, the challenge lies in continuously refining and improving our regulatory policies, guided by the principles of equity, quality, and inclusivity, to ensure every child’s right to education is respected, protected, and fulfilled. Policymakers must remain steadfast in learning from the successes and failures of different models. Only through continual refinement of policies and a steadfast commitment to equity can ePPPs fulfill their potential as catalysts for educational change.

As we delve deeper into the 21st century, the call to action for policymakers, educators, and stakeholders is clear: let us work collectively towards designing, implementing, and regulating ePPPs that guarantee every child, regardless of their background, an equal opportunity to learn, grow, and thrive in a rapidly evolving world. After all, our future depends on it.