This blog was written by Joel David Bond, who taught English in Iraq, and has recently completed a Masters in Education from the University of Nottingham, UK.

According to the UNHCR, a full 1% of the world’s population has been displaced as refugees and asylum seekers. That equates to roughly 78 million people who have fled their homes due to conflict, and the global refugee crisis is only growing.

Developed nations play some part in resettling these displaced, but what if assistance for refugees went beyond providing relocation services, and tackled the problem from both ends? What if a high-quality education in refugee-producing societies could create a future generation of empathic leaders who are poised to address home-turf crises with greater emotional intelligence?

Enter service-learning. The concept – pairing service work with education – is not new. It’s been around for decades, but mostly as an added extra to college courses or corporate team-building events. At the primary and secondary level – when minds are perhaps just building awareness and are most impressionable to social justice issues – service-learning is all but absent. And in conflict and post-conflict educational settings? Forget it. The limited resources there get channelled into the big three of reading, writing and arithmetic. Moreover, in conflict settings, existing resources often perpetuate cycles of violence through schooling, using outdated history books that espouse old racial biases and sectarian differences.

Private international schools can often provide a counterbalance to the often-crippled public education systems in post-conflict societies; however, their tendency to serve the privileged can further exacerbate a growing divide between the haves and have-nots. Yet from these elite institutions, future leaders, politicians, and large business owners are born.

I taught for 5 years at a private, international school in post-conflict Iraq, and my morning register was populated with family names of the local elite. My students’ parents are the leaders and influencers of today; my students, on track to be the movers and shakers of tomorrow. Whether they like it or not, many of my students were being groomed by their parents and their education for a life in politics, business or public service. They are essentially part of the top 1% in terms of societal wealth – in pathways to power that often contribute directly to producing the displaced 1%.

What if these young students could learn empathic leadership skills – through service-learning – to prepare them for a life beyond academics? What if they received an education, not just schooling for good test scores? And what if that education led to greater self-awareness as well as awareness of others who were from different classes, backgrounds or ethnicities?

These questions kickstarted an experiment that unfolded over several years, resulting in a programme designed to shift both attitudes and behaviours with regards to self-agency and being an agent of change.

From 2016 to 2019, I developed and ran a service-learning programme with my senior year English classes. The programme consisted of several components. First, was reading a selection of journal entries from notable past volunteers and philanthropists – famed diarists, do-gooders, and Peace Corps volunteers.

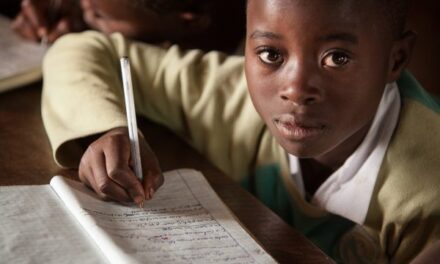

Second, was engaging in volunteer service work in the community. Over the course of the year, I coordinated and promoted several projects, from volunteer literacy and numeracy with primary students, Saturday sports clubs, English conversation for adult learners, and a capstone element – a donation drive and charity event for local internally-displaced people.

Second, was engaging in volunteer service work in the community. Over the course of the year, I coordinated and promoted several projects, from volunteer literacy and numeracy with primary students, Saturday sports clubs, English conversation for adult learners, and a capstone element – a donation drive and charity event for local internally-displaced people.

Finally, after each service project students were asked to write their own diary entries, mirroring the readings and prompted by reflection questions. The result was a qualitative shift in both attitudes and behaviours in the students involved. Survey responses after the programme demonstrated higher-than-average scores for metrics of intentional personal growth and empathy. When analysed alongside journal excerpts and interviews, students expressed a growing sense of gratitude and self-confidence, and reported positive shifts in behaviour towards more regular self-reflective journaling, better time management skills and increased service involvement after the programme.

Statistically, these shifts in attitudes and behaviours look great on paper – but will they have an actual effect on changing the world we live in? Only time will tell if these changes will have any staying power in these students’ lives. For most, it has been at the very least a grand perspective shift – pulling them out of comfort zones and into growth.

It’s my hope that programmes like this one can take root, not just in the schools of the private elite, but also the public schools – granting life-changing perspective shifts for students in conflict and post-conflict societies. Through creative approaches and role-model educators, we can engage students with our communities in ways that help develop empathic leadership. The kind of leadership that perhaps, one day, means students will lead with integrity and a vision for national and cultural development.

Perhaps the best testimony, though, comes from the mouths of the students themselves. Hanar*, a 19-year-old female student now pursuing undergraduate work in psychology and medicine, said of the programme: ‘It made me think of myself more as a leader. And [a leader] is not just you rising, it’s about helping other people rise with you.’

*Name changed for anonymity.

Joel David Bond can be contacted through LinkedIn or Twitter.