This blog was written after the 2021 UKFIET conference by the co-convenors of one of the six conference themes: Research methods: Building back better in international education and development research. The co-convenors are Bronwen McGrath, Global Programme Manager at Aga Khan Foundation; Elizabeth Walton, Associate Professor in Special and Inclusive Education in the School of Education at the University of Nottingham; and Yvette Hutchinson, Quality Assurance and Teacher Training Advisor, British Council.

Our conference theme, Research methods: Building back better in international education and development research, offered various questions and provocations to the international education development research community. These questions were answered with conceptual and empirical contributions, and through debate and discussion. The answers in turn raise more questions, indicating that interrogating research methods is vital in a quest for more inclusive, quality education for all.

How can international education and development research methods be reimagined to be authentically participatory and collaborative?

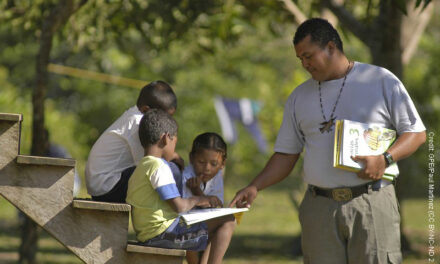

This first question is important because research problems have tended to be quite narrowly defined, with hierarchical relationships between researchers and participants, and among research partners, and practices that are extractive or characterised by “data robbing”. Presenters described innovative methods that offer different and creative ways to participate in research, like digital storytelling. These methods adopt an asset-based stance towards participants and their contexts, and recognise that different contexts require different approaches. Examples were given of research that created authentic spaces for community engagement in ways that expected participants to exercise their agency in the research process.

Much was said about the importance of reciprocal relationships, and repeated interactions, and the need for locally-led research. Projects have been successful when local researchers are involved, as this breaks down perceptions of researchers as a “bureaucratic elite”. These shifts from traditional research approaches and relationships are not easy, and presenters and delegates were frank about the challenges of trying to flatten hierarchies and disrupt inequitable power relationships, particularly given existing institutional cultures and mandates and the lack of “institutional wriggle room”. A call was made for “slow scholarship” that offers time to nurture research relationships that would enable us to build back better.

What constitutes ethical research in international education and development and what determines the boundaries of ethics in research?

This second question underpinning the presentations across our theme was closely related to the first, in that many contributions grappled with the sticky question of who benefits from current research arrangements. Several presentations shared how COVID-19 has led to new research practices and innovative methods to collect and share data as well as to obtain consent from participants. We heard about the challenges of remote interviews and telephone surveys and how patterns of inclusion and exclusion can be disrupted (or reinforced) through tech-enabled research methods. In one session, participants discussed how enumerators and other local partners are taking an increasingly leading role in the research process given limitations on travel. This raised important considerations of the wellbeing of local partners and the challenges of providing support at a distance.

How can contributors consider the hierarchies, prestige and power related to international research?

The third issue, linked to the first two questions, raised the issue of epistemology and indigenous knowledge systems. Presenters shared practice that privileged ways of conducting research that were inclusive and iterative. In one example, we learned about the importance of getting to know a community and gaining their trust. Participating in cultural activities allowed researchers to gain an understanding of ways of communicating with local communities. Establishing this understanding and gaining trust allowed a research partnership that was based on community-based values that esteemed communally-agreed capabilities. Disrupting hierarchies requires researchers to re-evaluate what they need to explore and how they will work within the local context. Acknowledging that what is valuable to an external researcher may not be of similar value to the ‘researched’ is a crucial aspect of the work to redistribute research power and will have significant implications for the role of donors in international education and training.

The theme convenors thank presenters for their well-prepared and thought-provoking presentations, and for engaging in robust discussions. We are confident that as a result of our deliberations, we are all more equipped to build back better in international education and development research.