This blog was written by Fabiana Maglio, Senior Specialist in Education and International Development consulting for donors and UN agencies; also volunteer as a UCL Alumni Mentor. This blog is part of the UCL Centre for International Education and Development (CEID) blog series on Education in the Time of COVID-19 and was originally published on the CEID blog site on 24 April 2020.

COVID-19 is impacting the way research is conducted in humanitarian settings. Field research, evaluations and data collection have suddenly come to a halt with researchers staying at home across the globe. Research projects are hitting pause, longitudinal research studies are facing significant disruption in data gathering, and there is a widespread concern about the future availability of grants or re-allocation of funding.

This pause in research activities provides an opportunity to think about research ethics in the time of COVID-19. Studies involving the participation of human subjects will have to change in the future: group gatherings for primary data collection must now be considered in terms of virus transmission. Mobile researchers must now consider themselves as potential carriers and spreaders of the virus into already vulnerable communities. How then might we re-consider research ethics to ensure the safety and well-being of research participants?

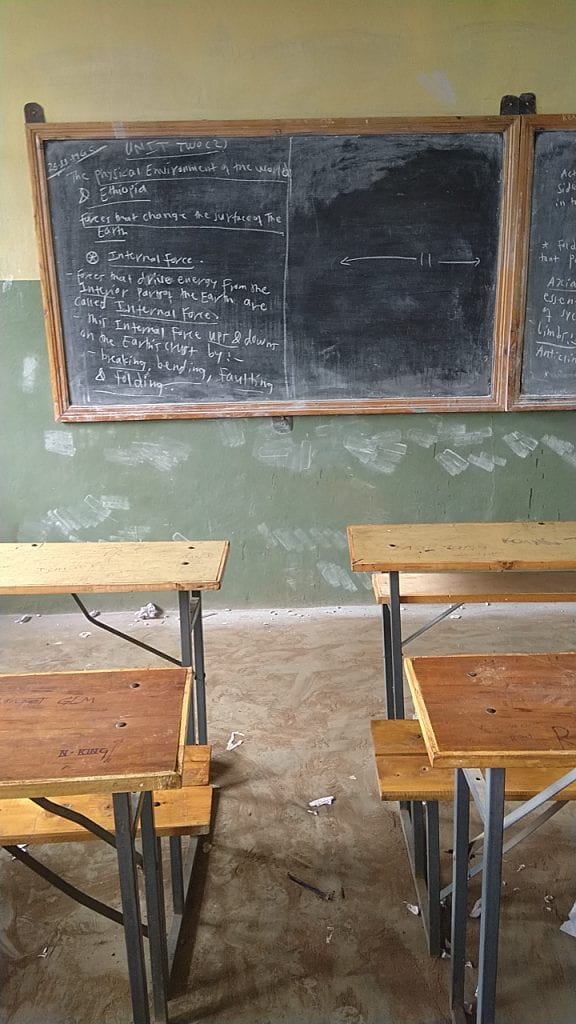

For me, the starting point is to understand the ethical responsibilities researchers have towards those involved in educational research at school and their communities, and how to reduce immediate harm in the current circumstances, just as Pauline Rose recently pointed out. Now more than ever before, research ethics should be at the forefront of every study that is undertaken during and after COVID-19 to protect children, researchers and wider communities who live in crisis settings.

It is also important to reflect on how to mitigate emerging, COVID-19-related challenges and ensure that research is still guided by an ethical compass. If data collection is ongoing, it is vital to take the appropriate steps to: maintain an equitable sample of participants in view of the extraordinary situation; adapt methods to be conducted in home environments so that they are non-intrusive; and ensure confidentiality and informed consent.

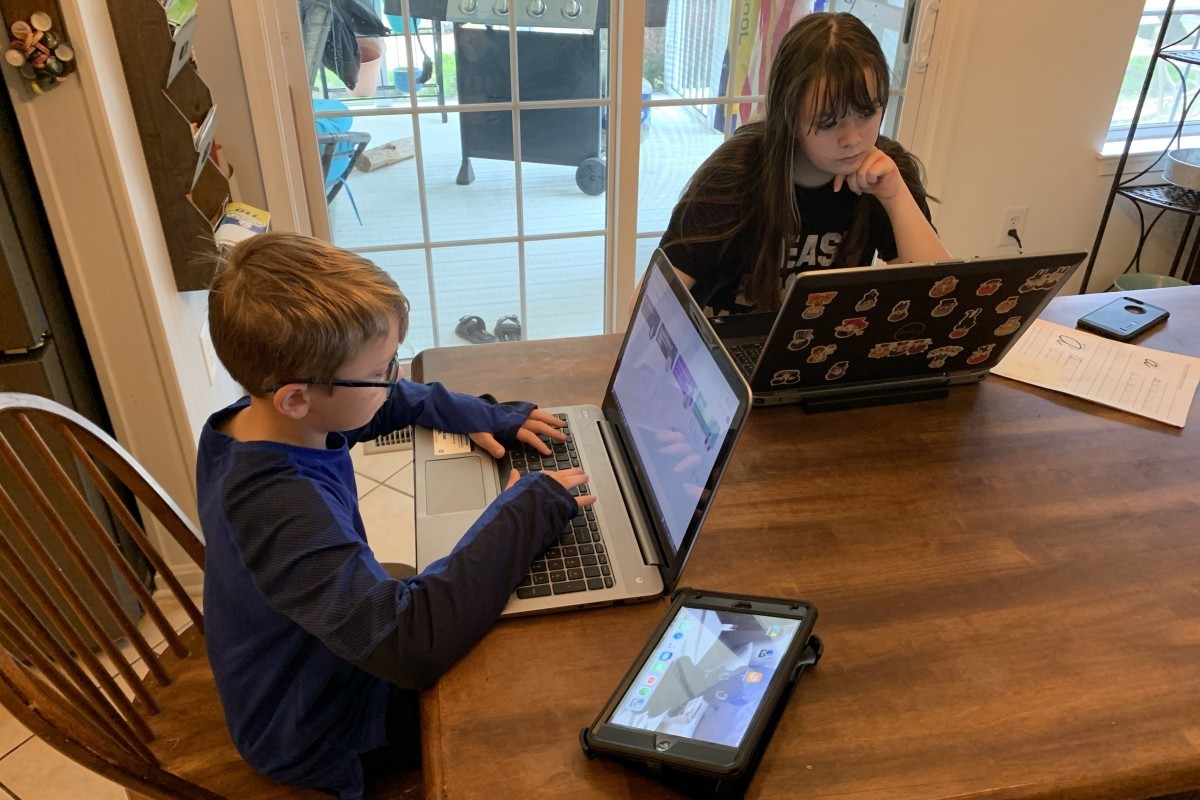

A lot of research will likely move online, posing new challenges. Researchers therefore must consider using audio-recorded consent if face-to-face interviews are not possible. Other aspects need to be considered too, such as who might be captured in the background of a video call. It is important to ensure that participants are aware of their unconditional right to withdraw and of the potential risks in taking part in the research, including the risk of an online session being overheard on either end of the computers.

A lot of research will likely move online, posing new challenges. Researchers therefore must consider using audio-recorded consent if face-to-face interviews are not possible. Other aspects need to be considered too, such as who might be captured in the background of a video call. It is important to ensure that participants are aware of their unconditional right to withdraw and of the potential risks in taking part in the research, including the risk of an online session being overheard on either end of the computers.

Remote research methods also present an opportunity to “give back” and foster solidarity. This may include conveying important messages to vulnerable school communities regarding the coronavirus, such as options on how to continue learning, access to health care, psychosocial support and other basic services. Although researchers cannot themselves be directly responsible to meet participants’ needs, they can use remote data collection as an opportunity to ensure referral so that school communities are not overlooked during this time of uncertainty. In case the research has paused or shut down, it is vital to reflect on the moral duty to provide pre-termination counselling to school participants via phone or video; report back on the expected use of the information they provided; and reallocate resources to continue to pay school enumerators and researchers who can no longer collect data.

The current lockdown provides humanitarian organisations with time to further invest in their staff’s capacity to conduct ethical research in the field after COVID-19. This process may include the design and provision of appropriate training on research ethics in practice to be undertaken by staff members, researchers and consultants. Online platforms and related training developed during this period are likely to be used when schools are able to reopen. It also includes the establishment and capacity development of local research teams in each unique country context, so that new hubs of expertise can support research and development locally during future pandemics, building on lessons learned from COVID-19. This process also involves new conversations and collaborations among academia, donors, and implementing actors around the role of both local and international research ethics committees to authorize future education research during a pandemic in accordance with the principles of justice, equity and solidarity. Ensuring that future field research, evaluations and data collection and analysis are undertaken applying the most rigorous standards and appropriate frameworks will help address important ethical dilemmas and ensure respect for the dignity, safety, and wellbeing of school participants.

The current lockdown provides humanitarian organisations with time to further invest in their staff’s capacity to conduct ethical research in the field after COVID-19. This process may include the design and provision of appropriate training on research ethics in practice to be undertaken by staff members, researchers and consultants. Online platforms and related training developed during this period are likely to be used when schools are able to reopen. It also includes the establishment and capacity development of local research teams in each unique country context, so that new hubs of expertise can support research and development locally during future pandemics, building on lessons learned from COVID-19. This process also involves new conversations and collaborations among academia, donors, and implementing actors around the role of both local and international research ethics committees to authorize future education research during a pandemic in accordance with the principles of justice, equity and solidarity. Ensuring that future field research, evaluations and data collection and analysis are undertaken applying the most rigorous standards and appropriate frameworks will help address important ethical dilemmas and ensure respect for the dignity, safety, and wellbeing of school participants.

Finally and most importantly, I think it is important to reflect on the moral imperative to ensure the agency and dignity of COVID-19-affected individuals and communities “in the storm breaking around them”, as recently pointed out by Hugo Slim. One way to translate this into ethically-sound school-based research in humanitarian settings after COVID-19 would be to invite local teachers to co-design studies, ensuring this fits into their routine practice, does not interfere with their teaching, is adapted based on their feedback and is endorsed by them before rolling out to additional schools. If local teachers do not own the process, it will remain another external research initiative that is great in principle but fails to embed in the day-to-day work of school communities.

If every crisis requires deeper consideration of how to better adapt and innovate, COVID-19 offers a unique opportunity to promote an informed debate on research ethics in humanitarian contexts.

Truly very nice articles, both of them! In this peculiar Covid period, “ringing the bell” on what it has the tendency to be left behind it is extremely important.

Thanks for taking the time to read it, Renato. Great to see your comment!