This NORRAG Debates: Philanthropy in Education is contributed by Alexandra Draxler, Senior Advisor at NORRAG and Former Education Specialist at UNESCO. She discusses the potentially devastating effect of COVID-19 on SDG4, pointing out that it is up to civil society institutions to ensure that decision – makers make education a priority. This article was originally published on the NORRAG website on 11 May 2020.

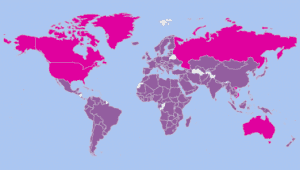

This poses some questions about how progress towards the SDGs may change in the new context of the coronavirus disease by pointing at a few opportunities for positive change as well as to potential opportunism resulting in negative outcomes. The conversation about the additional challenges to achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) on education posed by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is in its infancy. UNESCO has put into place a monitoring system with a staggering map that shows school closures over time and around the world. The first and most penetrating responses have been mainly about the asymmetrical impact school closures have on learners, as well as the need to ensure protection and support to teachers and their families.

Researchers do not have enough distance yet to do more than speculate on the longer-term prospects for education in light of COVID-19, and the media understandably is mainly focused on the scale of school closures. And yet, there are no prizes for guessing that any future progress reports will not be encouraging concerning the impact of the pandemic on SDG4. Five years after the adoption of the SDGs there is already evidence about the tensions, threats and opportunities[i] facing SDG4. COVID-19 is underscoring these, and clearly every single SDG4 target will have to be revisited in the light of evolving emergency responses, priorities and financing. Negative effects on equity, basic education completion, teachers’ roles and status, funding, and public policy may be to some extent mitigated in countries with strong governmental foresight and intervention. But problems will undoubtedly be exacerbated both by uneven national responses and by the worsening global economic climate. Opportunistic actors will be furthering their own interests with profit and influence taking priority over equity and the public good. In short, as the title suggests, will the window of opportunity result in positive social and system changes for education or be principally one that benefits opportunists?

Researchers do not have enough distance yet to do more than speculate on the longer-term prospects for education in light of COVID-19, and the media understandably is mainly focused on the scale of school closures. And yet, there are no prizes for guessing that any future progress reports will not be encouraging concerning the impact of the pandemic on SDG4. Five years after the adoption of the SDGs there is already evidence about the tensions, threats and opportunities[i] facing SDG4. COVID-19 is underscoring these, and clearly every single SDG4 target will have to be revisited in the light of evolving emergency responses, priorities and financing. Negative effects on equity, basic education completion, teachers’ roles and status, funding, and public policy may be to some extent mitigated in countries with strong governmental foresight and intervention. But problems will undoubtedly be exacerbated both by uneven national responses and by the worsening global economic climate. Opportunistic actors will be furthering their own interests with profit and influence taking priority over equity and the public good. In short, as the title suggests, will the window of opportunity result in positive social and system changes for education or be principally one that benefits opportunists?

Education and technologies

Anecdotal evidence and past research from countries where on-line contact with schools and teachers is being offered is unsurprising in suggesting that the proportion of the school population continuing to benefit from quality learning opportunities is heavily weighted in favour of higher socio-economic status of families. Access, and beyond access, affordability are immediate barriers for at least half of the world’s population. Those less advantaged face a range of frightening immediate and long-term consequences that include permanent school abandonment but also inequalities and vulnerabilities that can become entrenched and intergenerational. We will have to wait for evidence about how well on-line learning worked for those students who had enough access, in spite of self-interested claims by elements of the tech industry about the superiority of on-line learning. Learning by mobile phone—the connected medium for the vast majority of people in poor countries—has severe limitations for most types of learning. Affordability in most Media reports have glowing accounts about how teachers have jumped in, learned new skills and learned by doing what works and what works less well. Certainly, this has been part of the picture of admirable solidarity in the face of this unique crisis.

Fewer reports highlight the inevitable inequalities here too—for teachers who would have needed training, who have little or no internet experience to bring to the emergency or whose own family circumstances made response difficult or impossible. Teachers who did not have the skills or tools to make a dramatic transition may have professional and psychological handicaps going forward. In this new, world-wide shift for those who could to distance, on-line learning we will need time to assess both the many successes and the inevitable organizational problems or the need to know what parts of education cannot be relegated to technological solutions only. One of the risks is that vested interests will walk through the window of opportunity to push increasing on-line learning, although the evidence that technology is cost-effective over time and to scale is just not there (OECD 2016). Another scenario is that, given the widespread exposure to computerized learning in wealthy and middle-income countries, the experiences of teachers, learners and parents will lead to an informed dialogue and evidence-based decision-making.

Private sector involvement

We have seen a strong and nimble response by philanthropies to the pandemic. This is as it should be, and welcome.[ii] Encouragingly, during recent virtual meeting of the OECD Networks of Foundations Working for Development (netFWD) on “Philanthropy for Development in a New World Order: Let’s Reassess What Success Looks Like” (report not yet available), speakers and participants repeatedly stressed that in a context of weak or weakened governments and international cooperation, it is important for philanthropy to reassess how it can better contribute to robust and durable public service institutions, governmental or citizen-led.

As for the business sector, while many companies have reacted positively to protect exposed employees, education is not a front-line issue and governments are relied on to manage the responses. Technology companies offering hardware and learning materials for distance education are using the pandemic to mobilize support for longer-term investments in on-line learning. Concerning public-private partnerships, including for education, in hard times it is the governments that should expect to bear the economic impact of a crisis on a PPP by picking up the tab. This World Bank blog post perhaps inadvertently highlights the fluid definitions applied by most companies to the shared risk-taking supposedly inherent in public-private partnerships. Notably, it states: “It’s critical the private sector be assured that, as soon as problems arise, they can approach their public sector partners and share project impacts without fear of punitive actions that could unilaterally blame them for impacts”. This is not surprising, and it may be a sobering reminder for public policy decision makers that the fundamental objectives of the private and public sector “partners” are radically different. The decision by the IFC to freeze investments in for-profit “K – 12” schooling is a one that, if maintained, may give hope that private interests will be more closely monitored in the future by development agencies.

Thus, we can be cautiously optimistic that some foundations will use this crisis to adjust their support to complement governments with more longer-term, institution-building programmes. On the other hand, perhaps a less sanguine view of what can be expected from corporations in terms of contribution to the terms of the social compact will emerge to guide government and development policies at every level.

Priorities and Financing

Here is where arguably the SDGs will face the biggest danger and one in which equity will be at greatest risk because budgets of all countries will be strained, at the very least. Even in the unlikely eventuality that immediate needs related to the epidemic in the poorest countries are met by debt relief and additional financing, we can expect that meeting goals and targets established in a very different economic atmosphere will drop down in the list of priorities of development finance and country plans. One recent longitudinal modelling study (completed before the pandemic hit) concludes that by 2030 only 61% of young adults (aged 25–29) will have finished secondary education.

Although the discourse about meeting the targets will not suffer, funding will inevitably undergo major shifts that are not yet predictable. States, of course are the principal duty-bearers to uphold the right to education. It remains to be seen whether or not a significant number of governments, both of wealthy and poorer countries, will be distracted by the immediate health emergency from a sustained effort to build a better future. It will be up to civil society institutions to work to remind decision-makers everywhere that the SDG commitments are not luxuries. They are agreements democratically and transparently formulated and endorsed. Replacing them by rearranging priorities as seen from the political seat of here and now, urgent as that may seem, would extract a price from future generations.

Contribute: The NORRAG Blog provides a platform for debate and ideas exchange for education stakeholders. Therefore, if you would like to contribute to the discussion by writing your own blog post please visit our dedicated contribute page for detailed instructions on how to submit.

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s opinion, policy or activities

[i] The author has a chapter contribution to this just-published work.

[ii] See Lara Patil’s analysis of the philanthropic response to COVID-19 in a companion blog post entitled Disaster Philanthropy: Exploring the Power and Influence of the Private Sector and For-Profit Philanthropy in Pandemic Times.

Well lockdown has not dulled your brain(nor your sense of humour) Alexandra. That is a very broad survey indeed. I wonder if you are aware of the project based at Bristol where Simon McGrath and Leon Tikly coordinate research from various countries on a viewpoint of transformative public education responding to COVID while addressing long term underlying inequalities. It is very close to Amartya Sen’s human capabilities thinking plus of course PaulonFreire, the Vatican has just appointed a man called Zampini to look at post COVID human development and I know his thinking is steeped in Sen’s human capability theory.

Au revoir

Bill ozanne

No, I didn’t know and thanks for pointing it out. I’ll look into it, and with gratitude.