This blog was written by Lopa Shah, founding director of ELICIT, a social organisation driven to design alternatives for education in conflict and crisis affected regions, involving armed violence.

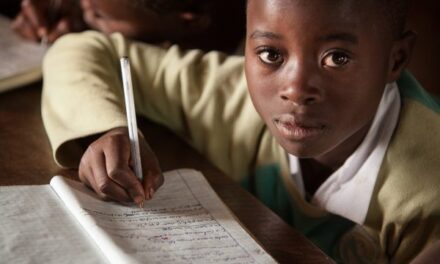

In contexts of protracted conflict, education is often discussed in terms of access, continuity and learning loss. These metrics matter. Yet they do not fully explain what enables learning amid chronic uncertainty, surveillance and disruption. From sustained practice in conflict-affected schools in Kashmir, a more foundational question emerges: what must education do for learning to be possible at all?

This reflection draws on practice-based research from mainstream schools in Indian-administered Kashmir, where prolonged political violence has shaped not only schooling systems but also how learners and educators relate to authority, safety and the future. It argues that education in such contexts must be understood as both a pedagogical and civic practice – one that responds to trauma, restores agency and rethinks curriculum as a matter of transitional justice.

Trauma-response patterns observed in schools

Prolonged exposure to conflict affects individuals and reshapes relational, cognitive and institutional patterns. The six trauma-response patterns identified in my practice in Kashmir-based school systems align with established findings across trauma psychology, affect theory and educational sociology.

| Trauma-response pattern | Core manifestation in schools | Theoretical grounding | Educational implication |

| Hyper-vigilance | Constant alertness, mistrust, rapid escalation, difficulty relaxing into learning | Polyvagal theory; stress neurobiology (Porges, 2011; Perry, 2006; van der Kolk, 2014) | Impairs attention, working memory, and peer relationships; classrooms feel unsafe |

| Avoidance | Withdrawal, silence, excessive compliance, or disruptive attention-seeking | Dissociation and avoidance responses (APA, 2013; van der Kolk, 2014) | Misread as low motivation; requires relational safety rather than behavioural control |

| Hopelessness / helplessness | Emotional numbing, passivity, low initiative | Learned helplessness; resilience research (Seligman, 1975; Masten, 2014) | Undermines persistence even when instruction improves |

| Constricted futurity | Inability to imagine alternatives, difficulty planning or aspiring | Foreshortened future; affective foreclosure (Nussbaum, 2011; Alexander, 2004) | Disrupts goal-setting, effort, and long-term learning trajectories |

| Erosion of self-care | Normalisation of harm, neglect of bodily and emotional care | Moral injury; trauma-informed care (Litz et al., 2009; SAMHSA, 2014) | Wellbeing practices fail without restored meaning and safety |

| Cognitive overload | Fatigue, poor concentration, inconsistent performance | Stress and executive function research (McEwen, 2012; Perry, 2006) | Brain prioritises survival over learning; intensification backfires |

| Systemic condition: collective trauma | Crisis-driven school culture, identity threat, institutional fragility | Sociological trauma theory (Alexander, 2004) | Trauma responses become normalised at policy, practice and relational levels |

Rethinking curriculum through patterns of meaning

Curriculum and assessment are often separated: one designs teaching, the other tests learning. In our work, assessment comes first. It sets the goals of education and the indicators of progress, which together define the curriculum. What we choose to measure shapes what we choose to teach. This is why we use backward design: clarify outcomes, design indicators, then build teaching practice. In Teach to ELICIT, curriculum names the changes we seek in children’s lives, and assessment tracks whether those changes are taking root.

Our pedagogical framework is both an internal handbook and a wider challenge to how curriculum is understood. Too often, curriculum is reduced to textbook content and exam performance, positioning children as receivers rather than agents. In fragile contexts, this becomes harmful. From our work in Kashmir, children living through protracted conflict cannot be reached by content alone. They also need safety, continuity, recognition and belonging. Curriculum, then, must shape patterns of looking inward and outward—how learners relate to self, others, and their world.

From patterns to pedagogy: a healing-centred approach

When curriculum is grounded in these patterns, it extends beyond the textbook and the lesson plan. It becomes a way of restoring meaning to disrupted lives, of linking knowledge to healing, and of anchoring children to a sense of possibility.

Key pedagogical shifts include:

- predictable structures and transparent decision-making to reduce perceived threat;

- relational noticing that counters invisibility and withdrawal;

- strength-based reflection to reopen future orientation without forcing optimism;

- backward design and flexible assessment to reduce cognitive overload;

- explicit modelling of care and boundaries as ethical practice.

Central to this is curious distancing: the educator’s capacity to remain emotionally present without becoming reactive. This supports regulation, reflection and ethical use of power in classrooms. As educators begin to reframe behaviour through this lens, changes in classroom dynamics follow. Teachers reported fewer confrontational interactions, increased student participation and greater willingness among students to articulate needs and emotions. Importantly, these shifts occurred without changes to curricular content or assessment difficulty, suggesting that relational and affective safety functioned as preconditions for learning rather than outcomes of it. Across cohorts, attrition among educators was highest in the first three months, mirroring periods of acute cognitive and emotional dissonance. However, when educators developed shared language and reflective routines around these six patterns, persistence increased markedly. This indicates that recognising trauma responses benefits not only students but also teachers’ capacity to remain engaged in volatile contexts.

Why this matters now

These findings challenge the idea that schooling can remain neutral amid structural violence. In protracted conflict, neutrality often reproduces harm by misreading survival behaviours as failure. What is needed is a shift from trauma-aware language to trauma-responsive systems. Healing-centred pedagogy aligns with the Right to Education’s emphasis on dignity, safety and participation (UNCRC Art. 28; ICESCR Art. 13) and extends peace education from values to institutional practice. By embedding psychosocial safety into everyday schooling, trauma-responsive cultures operationalise SDG 4.7 and INEE’s call for protective learning environments, recognising that emotional safety underpins educational continuity.

Conclusion

In conflict-affected settings, education is not merely instructional but relational and ethical. The six trauma-response patterns described here show how conflict shapes classroom behaviour and belief. Recognising them enables educators to respond with care rather than control. Healing-centred pedagogy is therefore a structural requirement for sustaining learning, teacher persistence, and civic trust. When schools attend to trauma intentionally, they can become spaces where agency is restored and futures cautiously re-imagined—advancing education as a practice of justice and peace.

More about Teach to ELICIT. And how to support ELICIT’s work.

thanks for info.