This blog was written by Le Thu Huong and Teerada Na Jatturas, UNESCO. Le Thu Huong is a Programme Specialist at the Education Policy Section, UNESCO – her expertise includes analysing and planning socio-economic and education policies and development aids in international education development. Teerada Na Jatturas has an MPhil in Digital Communications from the Communication and Media Research Institute, University of Westminster, UK, where she defended her thesis on digital rights of at-risk internet users. She is presently an intern at UNESCO analysing education and technology for educators.

Education institutions have been closed worldwide since early February to contain the transmission of the coronavirus (COVID-19). The imminent impact of these massive closures of schools evokes two crucial questions: Could these interrupted classes make learners lose their knowledge gained during the pre-COVID-19 era? How could this “learning loss” be mitigated? Before discussing these questions, it is vital to clarify the definition of the learning loss due to the school shutdown.

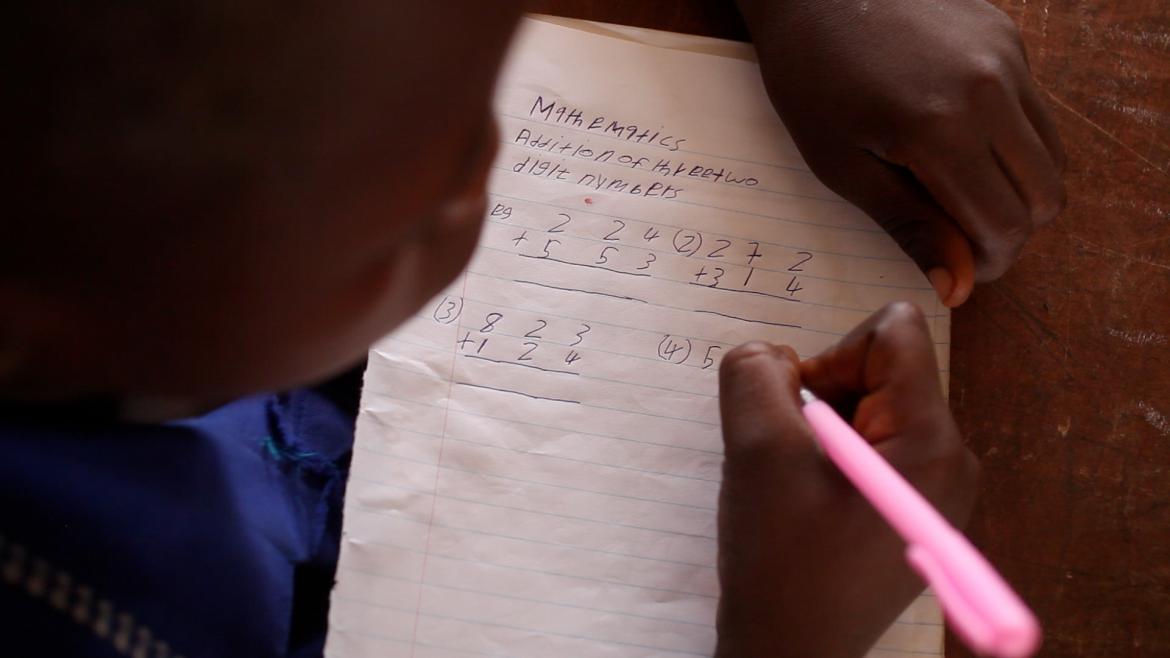

Learning loss refers to “any specific or general loss of knowledge and skills or to reversals in academic progress, most commonly due to extended gaps or discontinuities in a student’s education”. This is mostly caused by disrupted formal schooling including “summer learning loss”.

Learning loss refers to “any specific or general loss of knowledge and skills or to reversals in academic progress, most commonly due to extended gaps or discontinuities in a student’s education”. This is mostly caused by disrupted formal schooling including “summer learning loss”.

Learning loss has progressively taken place as more than two thirds of total enrolled learners worldwide have experienced disrupted learning directly and indirectly over the past three months. The existing data reveals three possible ways in which learning loss due to this crisis can occur:

- Reduction in the level of learning

Some researchers and practitioners have agreed that missing school impedes skill improvement, augments the disparity in learning, and therefore leads to the reduction in the learning levels of students, as seen in a scenario simulated by the World Bank on the effects of COVID-19 on the “learning curve” in countries with school shutdown.

This phenomenon is not new as it has been well documented in the Northwest Evaluation Association’s (NWEA) study of summer learning loss, which argues that students’ “growth trajectories” would either follow a “melt” path (wherein students “basically gained no ground during the school closures”) or a “slide” path (wherein students “lost ground academically during the closures at rates similar to those seen over the long summer break”). Although the observation can be applied to the COVID-19 crisis, the effects leave a more negative impact on many parents, who struggle to be bread winners and teachers for their children while ensuring that they can cope with both potential mental and health issues.

- Unequal levels of learning

Even if learning can continue through distance modalities, learning loss is still inevitable as several national examinations have been postponed or rescheduled, thereby creating delays or information gaps on student learning advancement without recognising their efforts. This may lead to misinformed or biased decisions on their educational progression. Some learners can still obtain the certification or qualification, but their actual knowledge and skills level might not equal to those of the previous cohorts during the pre-COVID-19 era, or those of the same cohorts who could access online learning facilities and resources. The latter problem underlines the digital divide, which has enlarged the “inequality of human capital growth for the affected cohorts” and has exacerbated the learning gaps among various segments of the same student cohorts within a country and among countries.

- Dropouts

Non-attendance during, and dropouts after, the school closures may cause further learning loss. This is due to prolonged absence from classes of learners who will drop out of schools or universities. This is worrying, particularly for the most marginalised or at-risk students, whose learning path is discontinued, leading to limited choices of work options. Even if some students manage to reintegrate into schooling and eventually graduate, they will expectantly plunge into underemployment and unemployment as they graduate into the pandemic. This results in the loss of years and resources they have invested in earlier education.

How could this “learning loss” be mitigated?

Our analysis suggests the following strategies are needed to fill in learning gaps, although we recognise that they need to be customised for specific contexts:

Optimising teaching and learning supports and resources during school closures

- Produce standardised lessons based on students’ age and their distance learning modalities.

- Maintain students’ learning engagement, for example, by verifying online presence using Attendance Tracking software, by organising entertaining activities alongside academic ones, by visiting them at home, and by following up students’ learning via phone calls and SMS texts.

- Provide learning alternatives for connectivity-constrained students. To illustrate, lessons broadcasted through television and radio, as well as blended learning modalities (e.g. using mobile SMS for individual communication, offering printed workbooks, and dispatching school materials) should be made available.

- Support families’ involvement in children’s learning and their digital lives. Common activities help to create solidarity, reduce stress and uplift the spirits of everyone involved.

Offsetting the learning loss when schools reopen

- Organise supplementary classes for at-risk pupils who are left behind when schools resume, while ensuring health, safety and system capacity are put in place.

- Consider using part of the summer holidays for teaching and learning to offset for the learning disruption during school closures.

Disclaimer: This article reflects only the views of the authors. UNESCO is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks