This blog was written by Thilanka Wijesinghe, a doctoral student at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge and a member of Cambridge Network for Disability and Education Research (CaNDER) and REAL Centre. She is also a Lecturer at the Department of Disability Studies, University of Kelaniya in Sri Lanka. This blog is part of a series from the REAL Centre reflecting on the impacts of the current COVID-19 pandemic on research work on international education and development. This blog is also published on the CaNDER website.

The pandemic bell rang in March 2020, resulting in immediate school closures in Sri Lanka, which continue to date. The Department of Education is promoting distance education with telecasted island-wide educational programmes and an official Moodle platform with online resources to support primary and secondary formal education in three languages. However, during this pandemic crisis, an area that has been instantaneously dropped, lost or completely invisible is the education of children with disabilities.

Situation for Deaf education

With the aim of viewing through the eyes of insiders and providing visibility to the field of disability in education, an online survey was carried out with seven educators in two residential, semi-government schools for the Deaf in Sri Lanka.

With the aim of viewing through the eyes of insiders and providing visibility to the field of disability in education, an online survey was carried out with seven educators in two residential, semi-government schools for the Deaf in Sri Lanka.

Both schools have more than 80 years of service and have been cornerstones for Deaf education in Sri Lanka, providing education to the profoundly hearing-impaired student populations from across the country. Most students come from low-income families and a significant percentage are from Deaf families. With the abrupt closure of schools, all students returned to their respective family homes. Reflecting on the current situation, the following themes were highlighted by the interviewees.

Priorities have changed: Right now, it is the food and safety, education comes later

The current focus, as the educators put it, was simply on ‘surviving’ and making sure that students and their families are safe and their basic needs, such as food, are fulfilled: “these children are already with disabilities; we need to make sure this pandemic doesn’t cause further disabilities to them” and “my biggest concern is whether they are getting something proper into their stomach”. With most parents being daily wagers, the most financially affected group in the country, getting the basic needs met is a significant concern. This echoes with views raised: “for some families the residential schools surpassed education, it was a place for survival… a source for a meal and a roof” for their child. Thus, in a context where safety and survival are at stake, the ‘mindset’ to plan education and learning for children with disabilities has temporarily shifted.

Weakened or lost connections

‘Lack of communication’ with Deaf students was highlighted, especially where parents are unable to sign. This results in parents being unable to effectively communicate with their child, while the child very often becomes “lonely and cornered” in their own home, with some opting to “linger on Facebook, television, online gaming or loitering”. This communication concern has a ripple effect on other significant aspects, such as psychological wellbeing of Deaf children, and the safety in their homes – children not following parents’ advice can result in domestic violence, for example. Some parents of teenage Deaf students are turning to teachers to resolve day-to-day conflicts, when they are unable to manage.

During the past two-month ‘lockdown’, the connection between families and schools has been through phone calls to check on families, provide information and send basic home tasks through WhatsApp and Viber channels. While these approaches seemed to have worked with some, the weakest link has been connecting with children in Deaf families. It was common to hear reports such as: “I have connected with the others but with the Deaf families, I have done nothing”; “we don’t know where they are”. The escalation of financial hardships was flagged, with some families relying on neighbours’ phones, having dysfunctional phones with no credit or no phone signal in remote areas – weakening the connections between the child, parent and teacher. Discrepancies in the distribution of support were described, with some children receiving support, whilst others were ‘lost’ or ‘unreachable’.

During this pandemic, the contextual variation and needs in each Deaf educational setting was viewed as being ‘different’. “In each class, each child’s concerns will be different. The plan is to go with the system, not mix up, organize, adapt, change and get on”. Educators noted that right now the most pressing need was to get connected: “go right down – make the root connection, link the teacher to parent and student, make clear connections”. Once connected, their ‘problems’ need to be assessed in order to find solutions; “right now we do what we think they need – this needs to change”.

Pedagogical approach to teaching for Deaf children

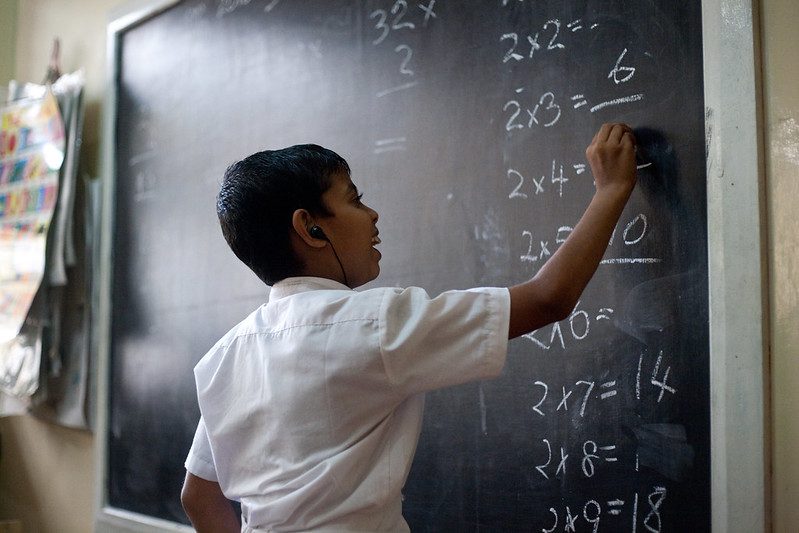

Sri Lanka’s Deaf education system follows the same government curriculum offered to the state schools. The Deaf schools have relied solely on conventional ‘live’ teaching – pedagogy based on face-to-face, teacher-directed sessions, multi-modal (spoken, written, shown, signed) with multiple opportunities for repetition. Teaching for Deaf children during this crisis is being viewed as “different and effortful”. Even though online and distance learning is encouraged as a country-wide approach for most children, it is new to these schools. Therefore, in the midst of constrained resources and novel teaching methods, the education of Deaf children is even more likely to be neglected. Weak aspects of the local Deaf education system appear more prominent in these testing times. For example, the rich variety in sign language variations used in Deaf schools has challenged identifying suitable sign language translations for the education programmes telecasted across the country.

Sri Lanka’s Deaf education system follows the same government curriculum offered to the state schools. The Deaf schools have relied solely on conventional ‘live’ teaching – pedagogy based on face-to-face, teacher-directed sessions, multi-modal (spoken, written, shown, signed) with multiple opportunities for repetition. Teaching for Deaf children during this crisis is being viewed as “different and effortful”. Even though online and distance learning is encouraged as a country-wide approach for most children, it is new to these schools. Therefore, in the midst of constrained resources and novel teaching methods, the education of Deaf children is even more likely to be neglected. Weak aspects of the local Deaf education system appear more prominent in these testing times. For example, the rich variety in sign language variations used in Deaf schools has challenged identifying suitable sign language translations for the education programmes telecasted across the country.

Adapting the ‘learning’ during and post-pandemic

- Learning to live with families, developing life skills

With the pandemic stalling Deaf education in Sri Lanka, educators saw this situation as a call for alternative and adapted possibilities. “The learning of the child will rely on the parent. Parents’ attitudes, abilities and knowledge will depend on the child’s learning. If parents are motivated and rightly directed to accessible resources, they would be able to teach their children.” However, educators remarked that most parents from local Deaf schools are ‘uneducated’ with limited literacy skills. During this prolonged break, the academic development of children at home is estimated as ‘zero’, with the majority commenting: “students will be idling, forget everything they learnt, they will return blank, empty”, impacting ‘all’ aspects of a Deaf child’s academic development. However, this situation can be turned into an opportunity of ‘learning to live’: “spending time with parents and hearing siblings, getting involved in activities of daily living and supporting livelihoods such as carpentry, farming and agriculture”. Some older students are enrolled in vocational programmes, such as bakery, agriculture and sewing, and could therefore use this time to practice vocational skills: “we just need to tell parents that this learning can easily be implemented in real life”.

With the pandemic stalling Deaf education in Sri Lanka, educators saw this situation as a call for alternative and adapted possibilities. “The learning of the child will rely on the parent. Parents’ attitudes, abilities and knowledge will depend on the child’s learning. If parents are motivated and rightly directed to accessible resources, they would be able to teach their children.” However, educators remarked that most parents from local Deaf schools are ‘uneducated’ with limited literacy skills. During this prolonged break, the academic development of children at home is estimated as ‘zero’, with the majority commenting: “students will be idling, forget everything they learnt, they will return blank, empty”, impacting ‘all’ aspects of a Deaf child’s academic development. However, this situation can be turned into an opportunity of ‘learning to live’: “spending time with parents and hearing siblings, getting involved in activities of daily living and supporting livelihoods such as carpentry, farming and agriculture”. Some older students are enrolled in vocational programmes, such as bakery, agriculture and sewing, and could therefore use this time to practice vocational skills: “we just need to tell parents that this learning can easily be implemented in real life”.

- Speed up or Select or Start again: Where from here?

Educators had a range of views in relation to formal Deaf education and associated national examinations (e.g. Grade 5 scholarship, Advanced-level examinations). Some expressed ‘speeding up’ the teaching and learning process by revising work, having extra after-school classes to ‘catch up’ the missed work. Some commented on modifying, prioritising and selecting at subject and content level, to teach essential components targeting national exams, while the majority suggested ‘re-starting’ on the basis that these are already strained systems. During the pandemic, “being aware of children’s ‘capacities’ and the overall readiness to work, including motivational talks, outdoor, free time to gradually settle down to routines” were accentuated, indicating the ‘deviance’ from the usual school implementation. Recalling the 2019 ‘Easter bombing’ crisis survival strategies, teaming up with parents to form “teacher-parent groups, identifying concerns and making contingency plans as a team to return to normalcy” were viewed as applicable to this context, to guide the ‘learning journey’.

Concerns and needs in Deaf education during and post-pandemic

The pandemic indisputably has raised an array of concerns and needs for when students go back to school. Concerns ranged from cleaning classrooms, to making arrangements to take in and maintain ‘healthy’ students – where the latter is seen as ‘a significant responsibility’, since, unlike in typical schools, “in Deaf schools children come from all over, tracing their health won’t be easy”. Suggestions were made on ‘gradation of student intake’, ‘joint quarantine’ of both students and staff, restricting daily travel and visitors, planning and firm implementation of social distancing practices within schools. Classroom practicalities such as “how do we teach a Deaf child with a mask?” were raised, emphasising the importance of seeing a teacher’s face during teaching and learning. Providing some ‘low-cost transparent masks’ was being explored as an option. Additionally, teachers voiced ‘their own life and safety’ being at ‘high risk’ with children and parents in classrooms.

Insights from conversations with these key stakeholders also identified the following recommendations:

At national level:

- Introduce a free, video call help-line for Deaf families with sign translators.

- Telecast a weekly/biweekly awareness programme in spoken and sign language, targeting both Deaf students and their families to:

- connect up with schools, so that teachers can offer support

- identify and address communication barriers within families

- identify ways of including children in daily activities, giving them responsibility

- keeping children informed of the pandemic and precautions they need to take

Schools should be responsible for:

- Circulating a short video with basic signs to parents, to enable them to communicate with their children.

- Carry out weekly parent and student checks and home-task plans.

- Post ‘lockdown’, set up mechanisms such as ‘WASH’ (Water, Sanitation and Hygiene) programmes and transport systems for the safe return of students, given that there might be reduction in the attendance.

Anticipating the future of Deaf education:

- Galvanise the use of a common Sign language to support the Deaf education system in Sri Lanka.

- Include new technology through the use of teaching aids (a basic tablet/ laptop) to efficiently facilitate ‘visual learning’.

- Recognise ‘parents’ as a central partners and include them in the education of the Deaf child.

Conclusion

Through this global pandemic, the reality is that every child’s education will be impacted. However, in this global battle to keep the education of our children afloat, we must realise the contextual realities, connect and adapt to learn and live, we MUST make sure that no one is left behind, especially those at greatest risk of exclusion.

Acknowledgments

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to all the teachers and head-teachers who took the time to engage in discussions with me during this unprecedented period. Also my sincere thanks to my doctoral supervisor, Prof. Nidhi Singal for encouraging me to undertake this research and supporting me, particularly during these difficult times.